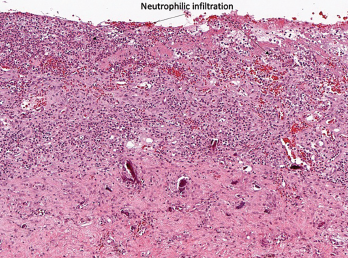

Figure 1A

No universal guidelines for the treatment of ICI-arthritis exist, but some suggestions follow. Management should always be discussed with the patient’s treating oncologist, especially if the patient is enrolled in a clinical trial.

For mono- or oligoarticular arthritis, intra-articular steroid injections can be helpful. For grade 1 arthritis, acetaminophen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be used. Low-dose corticosteroids (5–20 mg prednisone equivalent) can also be considered, tapering to the minimum required dose for symptom relief. (Note: Most oncology trial protocols allow patients to use the equivalent of up to 10 mg of prednisone daily and remain in the study.)

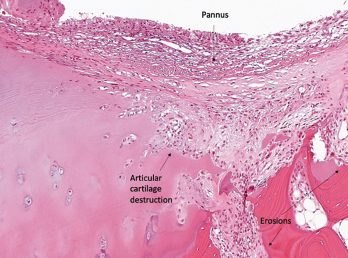

Figure 1B

Immunomodulating disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), such as hydroxychloroquine or sulfasalazine, can also be used to help taper corticosteroids, with the goal of bringing daily prednisone down to 10 mg or less.7 ICI therapy does not need to be held in mild, grade 1 cases.

For grade 2 arthritis, prednisone doses as high as 20–40 mg daily may be required. ICI treatment should generally be held until the arthritis has been controlled to a grade 1 level and prednisone has been tapered to 10 mg or less daily.

Grade 3 arthritis requires up to 40–60 mg of prednisone daily, and the ICI should be discontinued. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend rheumatology consultation and DMARD use for arthritis that does not respond to corticosteroids alone—after four

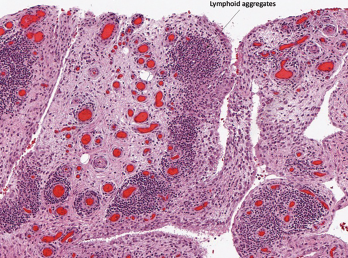

Figure 1C

Histopathology from bilateral total knee arthroplasty of a patient with bilateral ICI-arthritis. A) There is synovial infiltration by neutrophils and macrophages and fibrin deposition, but no necrosis. B) Pannus containing neutrophils, macrophages and few lymphocytes and plasma cells. There is articular cartilage destruction and bone erosion. C) Second knee explant with papillary processes of synovium showing many lymphoid aggregates, a few germinal centers and some neutrophils in the lining layer.

weeks for grade 2 arthritis and after two weeks for grade 3 arthritis.8

We favor early tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibition for high-grade arthritis because ICI-arthritis tends to persist for many months, and TNF inhibitors can significantly reduce corticosteroid exposure.9 Methotrexate can also be used, but its delayed onset of action and broad, rather than targeted, immunosuppressive effects are disadvantages. IL-6R blockers have also been used successfully, but less data are available on their safety and efficacy.10

Future studies should compare the safety and efficacy of corticosteroids vs. TNF inhibitors vs. methotrexate in the context of ICI-arthritis.

Case 2

A 53-year-old woman with metastatic renal cell carcinoma presents to the emergency department with neck weakness, ptosis and severe proximal myalgias shortly after her second pembrolizumab (an anti-PD-1) infusion. How should you evaluate and manage her?

ICI-Myositis & Myocarditis

Rheumatologists may not immediately recognize this patient’s atypical presentation, but the muscle weakness and myalgias should raise suspicion of a potential myositis. ICI-myositis has been described in 0.4% of patients treated with ICIs.11

In contrast to the usually painless, subacute proximal muscle weakness seen in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, ICI-myositis is often characterized by severe myalgia, sometimes with a lesser degree of weakness. Creatinine kinase (CK) elevation varies. A myasthenia-like distribution of muscle weakness, including ocular, bulbar and/or paraspinal muscles, can be present, but patients do not typically respond to pyridostigmine (see Figure 2).12,13

Muscle biopsy specimens demonstrate infiltrating T cells, myophagocytosis and necrotic myofibers.12

For patients with ICI-myositis, death is most commonly due to respiratory failure, presumably due to involvement of respiratory muscles; however, interstitial lung disease is uncommon.11 In addition to having features of myasthenia, ICI-myositis patients can have concomitant myocarditis, leading to conduction abnormalities and/or acute heart failure with fatality rates well over 50%.11,14

ICI-myositis tends to occur within two months of ICI initiation, although it can occur later as well. As with other irAEs, the most severe cases most frequently occur soon after treatment with the ICI begins. ICI-myositis, myasthenia and myocarditis are more common in those treated with combination ICIs (e.g., concurrent use of an anti-PD-L1 and an anti-CTLA-4) than in those treated with monotherapy.

ICI-Myositis & Myocarditis Management