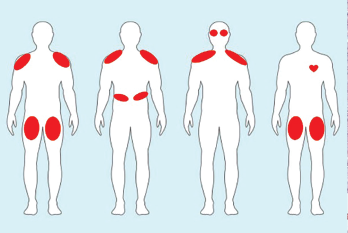

Figure 2. Examples of ICI-myositis muscle involvement. From left: 1) Symmetric, proximal large muscle involvement. 2) Proximal upper arm with diaphragmatic involvement leading to respiratory distress. 3) Proximal upper arm with neck weakness and ocular muscle ptosis resembling myasthenia gravis. 4) Bilateral thigh involvement with myocarditis.

In the case presented, the key first step in management is prompt recognition of the problem and its potential for severe morbidity and mortality, including concomitant myocarditis. This patient should be hospitalized and managed by a multidisciplinary team that optimally includes a neurologist and a rheumatologist, as well as a cardiologist if troponin levels are elevated.

CK and troponin should be tracked over time, even if the patient has no cardiac complaints on initial presentation. An electrocardiogram and an echocardiogram should also be performed. In patients with suspected myocarditis, cardiac MRI and endomyocardial biopsy are often performed.

When bulbar symptoms are present, a swallowing evaluation is indicated. Pulmonary function tests with inspiratory and expiratory pressures are helpful when diaphragmatic or intercostal muscle involvement is suspected. If the diagnosis is unclear, electromyography and nerve conduction studies can help distinguish a neuropathic process from true ICI-induced myasthenia gravis.

Patients should be treated with high-dose corticosteroids, sometimes pulse dosed, depending on the severity of presentation. IVIG and plasmapheresis are the most commonly used steroid-sparing agents, but rituximab, TNF inhibitors, mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus have also been used.11,12

In patients with myocarditis, early treatment with very high-dose corticosteroids is associated with better outcomes.15 TNF inhibitors are often used in refractory cases. Clinicians successfully used abatacept, a CTLA-4 agonist, in one refractory case; however, given its mechanism of action, some have expressed concern that the therapy may also promote tumor growth and negatively affect cancer outcomes.16

Case 3

A 57-year-old woman with a long history of rheumatoid arthritis in remission on methotrexate and adalimumab has developed a new diagnosis of metastatic melanoma. Her oncologist wants to know if she can be treated with an ICI and also asks for input on her rheumatoid arthritis medications.

Rheumatic Patients Requiring ICIs

Patients with known autoimmune diseases were excluded from early trials of ICIs, so we lack prospective data regarding their safety or efficacy in rheumatic disease patients. However, in retrospective studies, these patients seem to fare as well as those without underlying autoimmune disease.17 Thus, ICI therapy should not be withheld just because a patient has an underlying autoimmune condition.

However, about 50% of rheumatic disease patients have a flare of their underlying condition after ICI initiation.18 Clinicians need to consider the severity of autoimmune disease; arthritis flares, for example, can be mild and treatable.18 They must also consider the stage and aggressiveness of the cancer, as well as the availability of other cancer treatment options such as targeted therapies.

About one-third of patients with autoimmune disease develop a de novo irAE after treatment with an ICI (i.e., an autoimmune complication other than their underlying disease). This rate is lower if patients are on baseline treatment or immunosuppression.

However, some data suggest that patients on immunosuppression at the time of ICI initiation have less robust cancer responses.19,20 Therefore, discontinuing immunosuppression prior to ICI should be strongly considered, especially if the autoimmune disease is not life-threatening.

In this case, the patient’s rheumatoid arthritis had been in remission for a long time. We would recommend stopping both the methotrexate and adalimumab prior to ICI initiation. The clinician could manage any rheumatoid arthritis flare with corticosteroids, resumption of her TNF inhibitor and potentially methotrexate, as needed.

Case 3 Continued

The patient is started on combination ipilimumab/nivolumab (an anti-CTLA-4 and an anti-PD-1). After two months of treatment, she has a severe arthritis flare (grade 3) involving multiple joints that requires resumption of adalimumab as well as a short course of high-dose prednisone. Could the addition of these agents impact her cancer survival?

Impact of Immunosuppression on Cancer

There’s a paucity of high-quality data on the impact of immunosuppression on cancer survival in ICI-treated patients. A retrospective study of patients with ICI-related hypophysitis demonstrated that high-dose corticosteroids were associated with a significant reduction in survival compared with low-dose corticosteroids.21

Retrospective and preclinical studies examining the impact of TNF inhibitors on survival in patients with ICI-colitis give reassuring safety signals with respect to cancer response.22,23 But one retrospective study of 1,250 ICI-treated melanoma patients from 2012–17 found that those treated with TNF inhibitors for high-grade irAEs had worse survival than those treated with corticosteroids alone.24

However, confounding by indication may have impacted these results because the vast majority of TNF inhibitor-treated patients received the treatment for colitis following ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) monotherapy and not anti-PD-1 therapy, during a period when ICI-colitis fatality rates were higher than they are now. In addition, ICI-colitis, which is frequently treated by TNF inhibitors in this setting, tends to occur earlier than other irAEs, and this may have introduced a time-dependent bias.

None of the published prospective ICI-arthritis cohorts have been powered to address the impact of treatment for irAEs on survival.9,25 Collaborative efforts are underway to pool ICI-arthritis patient data prospectively to answer questions about the impact of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs on survival.

Table 1: Key Differences Between RA & ICI Arthritis