3D rendering of immune checkpoint molecules on a T cell and a dendritic cell.

Alpha Tauri 3D Graphics / shutterstock.com

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as anti-programmed cell-death 1/programmed death-ligand 1 (anti-PD-1/PD-L1) or anti-CTL-associated protein (anti-CTLA-4), have dramatically changed the treatment of advanced cancers over the past decade. ICIs block T cell inhibition, thus increasing the anti-tumor immune response. ICIs are used not only for metastatic cancer, but also as adjuvant treatment for some stage 3 cancers, and they are most effective for tumors with a high mutational burden.

However, these agents often cause immune-related adverse events (irAEs). Of all such adverse events, 6–7% are rheumatic in nature.1 Given the growing use of ICIs, particularly for common malignancies, such as non-small cell lung cancer, most rheumatologists will evaluate and manage such patients in routine clinical practice. This field is in its infancy, so the evidence guiding treatment decisions is sparse. What follows are some typical case scenarios and our answers to questions that often arise.

Case 1

A 71-year-old man with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer treated with three months’ of nivolumab (an anti-PD-1) develops joint pain, swelling and stiffness, most severe in the right knee. Knee arthrocentesis is consistent with an inflammatory arthritis. After one month of relief from an intra-articular steroid injection, he presents to you with bilateral, symmetrical arthritis in his metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, wrists, shoulders and knees. How should you treat him?

ICI-arthritis

This patient has developed an inflammatory arthritis, ICI-arthritis, precipitated by anti-PD-1 treatment. ICI-arthritis occurs in 4% of patients treated with an ICI.2 The median time to onset is four months; however, it can occur days after the first infusion of ICI or even months after ICI treatment has been discontinued.3

Patients with ICI-arthritis may present with mono- or oligoarthritis, often involving the knees; a rheumatoid arthritis-like, polyarticular pattern that may overlap with polymyalgia rheumatica; or more rarely, a spondyloarthritis pattern (see Table 1,4).

Over time, a lower extremity oligoarthritis may evolve to a symmetrical, polyarticular pattern. Less common presentations, including a tenosynovitis-only pattern and osteoarthritis exacerbations, have been described.

Evaluation of these patients should include bloodwork, arthrocentesis, if possible, and imaging. Other causes of inflammatory arthritis, such as infection, crystal disease or reactive arthritis, should be ruled out. Rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody are positive in about 10% of patients, but it is unknown whether this reflects post-ICI treatment seroconversion or persistence of pre-treatment seropositivity.3

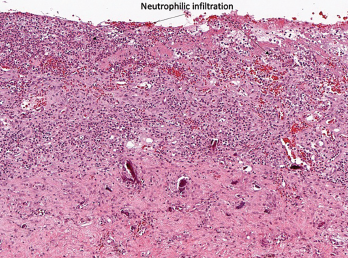

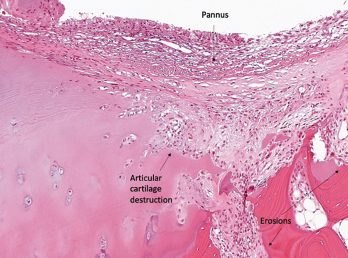

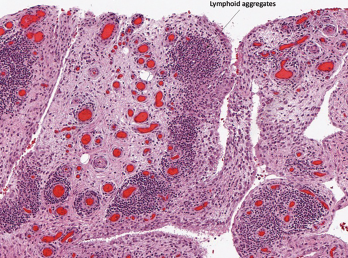

Although ICI-arthritis is often too acute for erosive disease to be noted on X-ray imaging, erosions have been demonstrated by ultrasound in some patients, and proliferative pannus formation and bone erosions can also be seen pathologically (see Figures 1A–C, opposite).5 Review of patients’ surveillance positron emission tomography (PET) scans can help identify bone metastases, if they are present, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be used for patients with atypical presentations.

irAEs are assigned a grade as determined by the Common Terminology for Cancer Adverse Effects (CTCAE) criteria.6 Grades 1 and 2 are defined as mild and moderate pain, respectively, and inflammation that does not interfere with activities of daily living (ADLs); to achieve grade 3, severe pain must interfere with ADLs.

ICI-myositis tends to occur within two months of ICI initiation, although it can occur later as well. As with other irAEs, the most severe cases most frequently occur soon after treatment with the ICI begins.

CTCAE grading does a poor job of distinguishing the severity of arthritis activity. Thus, clinicians may find it useful to monitor response to therapy using rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures, such as the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), the Disease Activity Score for 28 Joints (DAS28) and the Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3).

Treatment Approaches

Figure 1A

No universal guidelines for the treatment of ICI-arthritis exist, but some suggestions follow. Management should always be discussed with the patient’s treating oncologist, especially if the patient is enrolled in a clinical trial.

For mono- or oligoarticular arthritis, intra-articular steroid injections can be helpful. For grade 1 arthritis, acetaminophen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be used. Low-dose corticosteroids (5–20 mg prednisone equivalent) can also be considered, tapering to the minimum required dose for symptom relief. (Note: Most oncology trial protocols allow patients to use the equivalent of up to 10 mg of prednisone daily and remain in the study.)

Figure 1B

Immunomodulating disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), such as hydroxychloroquine or sulfasalazine, can also be used to help taper corticosteroids, with the goal of bringing daily prednisone down to 10 mg or less.7 ICI therapy does not need to be held in mild, grade 1 cases.

For grade 2 arthritis, prednisone doses as high as 20–40 mg daily may be required. ICI treatment should generally be held until the arthritis has been controlled to a grade 1 level and prednisone has been tapered to 10 mg or less daily.

Grade 3 arthritis requires up to 40–60 mg of prednisone daily, and the ICI should be discontinued. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend rheumatology consultation and DMARD use for arthritis that does not respond to corticosteroids alone—after four

Figure 1C

Histopathology from bilateral total knee arthroplasty of a patient with bilateral ICI-arthritis. A) There is synovial infiltration by neutrophils and macrophages and fibrin deposition, but no necrosis. B) Pannus containing neutrophils, macrophages and few lymphocytes and plasma cells. There is articular cartilage destruction and bone erosion. C) Second knee explant with papillary processes of synovium showing many lymphoid aggregates, a few germinal centers and some neutrophils in the lining layer.

weeks for grade 2 arthritis and after two weeks for grade 3 arthritis.8

We favor early tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibition for high-grade arthritis because ICI-arthritis tends to persist for many months, and TNF inhibitors can significantly reduce corticosteroid exposure.9 Methotrexate can also be used, but its delayed onset of action and broad, rather than targeted, immunosuppressive effects are disadvantages. IL-6R blockers have also been used successfully, but less data are available on their safety and efficacy.10

Future studies should compare the safety and efficacy of corticosteroids vs. TNF inhibitors vs. methotrexate in the context of ICI-arthritis.

Case 2

A 53-year-old woman with metastatic renal cell carcinoma presents to the emergency department with neck weakness, ptosis and severe proximal myalgias shortly after her second pembrolizumab (an anti-PD-1) infusion. How should you evaluate and manage her?

ICI-Myositis & Myocarditis

Rheumatologists may not immediately recognize this patient’s atypical presentation, but the muscle weakness and myalgias should raise suspicion of a potential myositis. ICI-myositis has been described in 0.4% of patients treated with ICIs.11

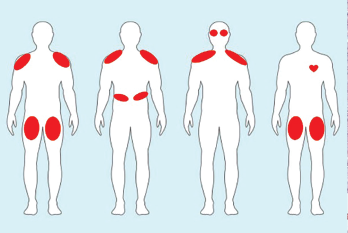

In contrast to the usually painless, subacute proximal muscle weakness seen in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, ICI-myositis is often characterized by severe myalgia, sometimes with a lesser degree of weakness. Creatinine kinase (CK) elevation varies. A myasthenia-like distribution of muscle weakness, including ocular, bulbar and/or paraspinal muscles, can be present, but patients do not typically respond to pyridostigmine (see Figure 2).12,13

Muscle biopsy specimens demonstrate infiltrating T cells, myophagocytosis and necrotic myofibers.12

For patients with ICI-myositis, death is most commonly due to respiratory failure, presumably due to involvement of respiratory muscles; however, interstitial lung disease is uncommon.11 In addition to having features of myasthenia, ICI-myositis patients can have concomitant myocarditis, leading to conduction abnormalities and/or acute heart failure with fatality rates well over 50%.11,14

ICI-myositis tends to occur within two months of ICI initiation, although it can occur later as well. As with other irAEs, the most severe cases most frequently occur soon after treatment with the ICI begins. ICI-myositis, myasthenia and myocarditis are more common in those treated with combination ICIs (e.g., concurrent use of an anti-PD-L1 and an anti-CTLA-4) than in those treated with monotherapy.

ICI-Myositis & Myocarditis Management

Figure 2. Examples of ICI-myositis muscle involvement. From left: 1) Symmetric, proximal large muscle involvement. 2) Proximal upper arm with diaphragmatic involvement leading to respiratory distress. 3) Proximal upper arm with neck weakness and ocular muscle ptosis resembling myasthenia gravis. 4) Bilateral thigh involvement with myocarditis.

In the case presented, the key first step in management is prompt recognition of the problem and its potential for severe morbidity and mortality, including concomitant myocarditis. This patient should be hospitalized and managed by a multidisciplinary team that optimally includes a neurologist and a rheumatologist, as well as a cardiologist if troponin levels are elevated.

CK and troponin should be tracked over time, even if the patient has no cardiac complaints on initial presentation. An electrocardiogram and an echocardiogram should also be performed. In patients with suspected myocarditis, cardiac MRI and endomyocardial biopsy are often performed.

When bulbar symptoms are present, a swallowing evaluation is indicated. Pulmonary function tests with inspiratory and expiratory pressures are helpful when diaphragmatic or intercostal muscle involvement is suspected. If the diagnosis is unclear, electromyography and nerve conduction studies can help distinguish a neuropathic process from true ICI-induced myasthenia gravis.

Patients should be treated with high-dose corticosteroids, sometimes pulse dosed, depending on the severity of presentation. IVIG and plasmapheresis are the most commonly used steroid-sparing agents, but rituximab, TNF inhibitors, mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus have also been used.11,12

In patients with myocarditis, early treatment with very high-dose corticosteroids is associated with better outcomes.15 TNF inhibitors are often used in refractory cases. Clinicians successfully used abatacept, a CTLA-4 agonist, in one refractory case; however, given its mechanism of action, some have expressed concern that the therapy may also promote tumor growth and negatively affect cancer outcomes.16

Case 3

A 57-year-old woman with a long history of rheumatoid arthritis in remission on methotrexate and adalimumab has developed a new diagnosis of metastatic melanoma. Her oncologist wants to know if she can be treated with an ICI and also asks for input on her rheumatoid arthritis medications.

Rheumatic Patients Requiring ICIs

Patients with known autoimmune diseases were excluded from early trials of ICIs, so we lack prospective data regarding their safety or efficacy in rheumatic disease patients. However, in retrospective studies, these patients seem to fare as well as those without underlying autoimmune disease.17 Thus, ICI therapy should not be withheld just because a patient has an underlying autoimmune condition.

However, about 50% of rheumatic disease patients have a flare of their underlying condition after ICI initiation.18 Clinicians need to consider the severity of autoimmune disease; arthritis flares, for example, can be mild and treatable.18 They must also consider the stage and aggressiveness of the cancer, as well as the availability of other cancer treatment options such as targeted therapies.

About one-third of patients with autoimmune disease develop a de novo irAE after treatment with an ICI (i.e., an autoimmune complication other than their underlying disease). This rate is lower if patients are on baseline treatment or immunosuppression.

However, some data suggest that patients on immunosuppression at the time of ICI initiation have less robust cancer responses.19,20 Therefore, discontinuing immunosuppression prior to ICI should be strongly considered, especially if the autoimmune disease is not life-threatening.

In this case, the patient’s rheumatoid arthritis had been in remission for a long time. We would recommend stopping both the methotrexate and adalimumab prior to ICI initiation. The clinician could manage any rheumatoid arthritis flare with corticosteroids, resumption of her TNF inhibitor and potentially methotrexate, as needed.

Case 3 Continued

The patient is started on combination ipilimumab/nivolumab (an anti-CTLA-4 and an anti-PD-1). After two months of treatment, she has a severe arthritis flare (grade 3) involving multiple joints that requires resumption of adalimumab as well as a short course of high-dose prednisone. Could the addition of these agents impact her cancer survival?

Impact of Immunosuppression on Cancer

There’s a paucity of high-quality data on the impact of immunosuppression on cancer survival in ICI-treated patients. A retrospective study of patients with ICI-related hypophysitis demonstrated that high-dose corticosteroids were associated with a significant reduction in survival compared with low-dose corticosteroids.21

Retrospective and preclinical studies examining the impact of TNF inhibitors on survival in patients with ICI-colitis give reassuring safety signals with respect to cancer response.22,23 But one retrospective study of 1,250 ICI-treated melanoma patients from 2012–17 found that those treated with TNF inhibitors for high-grade irAEs had worse survival than those treated with corticosteroids alone.24

However, confounding by indication may have impacted these results because the vast majority of TNF inhibitor-treated patients received the treatment for colitis following ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) monotherapy and not anti-PD-1 therapy, during a period when ICI-colitis fatality rates were higher than they are now. In addition, ICI-colitis, which is frequently treated by TNF inhibitors in this setting, tends to occur earlier than other irAEs, and this may have introduced a time-dependent bias.

None of the published prospective ICI-arthritis cohorts have been powered to address the impact of treatment for irAEs on survival.9,25 Collaborative efforts are underway to pool ICI-arthritis patient data prospectively to answer questions about the impact of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs on survival.

Table 1: Key Differences Between RA & ICI Arthritis

| Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | ICI Arthritis | |

|---|---|---|

| Acuity of arthritis | Subacute (>6 weeks) | Acute (days–weeks) |

| Seropositivity | Very common (70–80%) | Uncommon (10%) |

| Shared epitope (SE) | Both more likely to have at least one SE allele compared to general population, though homozygosity more common in RA4 | |

| Steroid treatment | Can often be managed with steroid doses less than 20 mg | High doses sometimes required for relief (40 mg+) |

| Erosive disease | Common | Can occur |

| Synovial biopsy | Lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, germinal centers, few neutrophils | Macrophage and neutrophil infiltration, germinal centers may be present |

Case 3 Continued

The patient’s arthritis is brought under control on adalimumab, and prednisone is tapered off. Can her ICI be resumed?

Resuming ICI

In general, ICI rechallenge is not considered after life-threatening irAEs, such as myocarditis or pneumonitis. A study of patients who had positive tumor responses prior to experiencing a severe event found no difference in cancer outcomes between those who resumed ICI therapy vs. those who permanently discontinued the ICI.26 Thus, ICI resumption may not always be necessary.

Clinicians may consider resuming an ICI once a patient’s irAE has been downgraded to grade 1, requiring minimal immunosuppression (i.e., prednisone equivalent to ≤10 mg).

Results from rechallenge have been mixed, ranging from no recurrence to severe recurrence to completely different irAEs. Recurrence is more common when the original irAE occurred soon after ICI initiation.27 Class switching (e.g., anti-CTLA-4 to anti-PD-1), if appropriate, has also been shown help prevent recurrence in some cases.

If her cancer warrants ongoing treatment, one could consider rechallenging this patient with anti-PD-1 monotherapy with concomitant adalimumab. This decision should be made jointly with the patient and her oncologist.

Other irAEs

In addition to ICI-arthritis, several other rheumatic irAEs can occur with ICI use. ICI-polymyalgia rheumatica is common and can present independently or in conjunction with ICI-arthritis. ICI-sicca is a rarer event, which predominantly involves the mouth rather than the eyes.

ICI-fasciitis is rare, but carries the potential for severe morbidity. It manifests initially as swelling and nonpitting edema of the legs and forearms, causing pain and stiffness, and can progress to severe fibrotic disease if not treated promptly. MRI imaging and/or biopsy can be helpful in making a fasciitis diagnosis.

Vasculitis and sarcoidosis have also been reported as uncommon rheumatic irAEs. Interestingly, systemic lupus erythematosus does not seem to occur as an irAE, although subacute cutaneous lupus does rarely manifest as an irAE.

Regardless of presentation, rheumatologists may be called upon to aid patients and physicians in the management of irAEs, given their autoimmune nature. Symptom recognition, prompt treatment and coordinated care with the oncologist, as well as other specialists, can minimize a patient’s organ damage and improve their quality of life.

Nilasha Ghosh, MD, MS, is a rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, with special interests in education and the intersection of rheumatology and oncology.

Nilasha Ghosh, MD, MS, is a rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, with special interests in education and the intersection of rheumatology and oncology.

Anne R. Bass, MD, is a rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and a professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. She leads a multidisciplinary team studying the clinical and biological characteristics of checkpoint inhibitor-associated autoimmunity.

Anne R. Bass, MD, is a rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and a professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. She leads a multidisciplinary team studying the clinical and biological characteristics of checkpoint inhibitor-associated autoimmunity.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Dr. Edward DiCarlo (Hospital for Special Surgery) for providing the histopathology images relevant to this publication.

References

- Angelopoulou F, Bogdanos D, Dimitroulas T, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal manifestations. Rheumatol Int. 2021 Jan;41(1):33–42.

- Kostine M, Rouxel L, Barnetche T, et al. Rheumatic disorders associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with cancer—clinical aspects and relationship with tumour response: A single-centre prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Mar;77(3):393–398.

- Ghosh N, Tiongson MD, Stewart C, et al. Checkpoint inhibitor–associated arthritis: A systematic review of case reports and case series. J Clin Rheumatol. 2021 Apr 25;10.1097/RHU.0000000000001370.

- Cappelli LC, Dorak MT, Bettinotti MP, et al. Association of HLA-DRB1 shared epitope alleles and immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019 Mar 1;58(3):476–480.

- Albayda J, Dein E, Shah AA, et al. Sonographic findings in inflammatory arthritis secondary to immune checkpoint inhibition: A case series. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2019 Jun 12;1(5):303–307.

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0. National Cancer Institute. Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. 2017.

- Roberts J, Smylie M, Walker J, et al. Hydroxychloroquine is a safe and effective steroid-sparing agent for immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced inflammatory arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019 May;38(5):1513–1519.

- Thompson JA, Schneider BJ, Brahmer J, et al. Management of immunotherapy-related toxicities, version 1.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019 Mar 1;17(3):255–289.

- Braaten TJ, Brahmer JR, Forde PM, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced inflammatory arthritis persists after immunotherapy cessation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Mar;79(3):332–338.

- Kim ST, Tayar J, Trinh VA, et al. Successful treatment of arthritis induced by checkpoint inhibitors with tocilizumab: A case series. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Dec;76(12):2061–2064.

- Aldrich J, Pundole X, Tummala S, et al. Inflammatory myositis in cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 May;73(5):866–874.

- Touat M, Maisonobe T, Knauss S, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related myositis and myocarditis in patients with cancer. Neurology. 2018 Sep 4;91(10):e985–e994.

- Moreira A, Loquai C, Pföhler C, et al. Myositis and neuromuscular side-effects induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2019 Jan;106:12–23.

- Anquetil C, Salem JE, Lebrun-Vignes B, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated myositis: Expanding the spectrum of cardiac complications of the immunotherapy revolution. Circulation. 2018 Aug 14;138(7):743–745.

- Mahmood SS, Fradley MG, Cohen JV, et al. Myocarditis in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Apr 24;71(16):1755–1764.

- Salem JE, Allenbach Y,Vozy A, et al. Abatacept for severe immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jun 13;380(24):2377–2379.

- van der Kooij MK, Suijkerbuijk KPM, Dekkers OM, et al. Safety and efficacy of checkpoint inhibition in patients with melanoma and preexisting autoimmune disease. Ann Intern Med. 2021 Sep;174(9):1345–1346.

- Abdel-Wahab N, Shah M, Lopez-Olivo MA, Suarez-Almazor ME. Use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of patients with cancer and preexisting autoimmune disease. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Jul 17;169(2):133–134.

- Menzies AM, Johnson DB, Ramanujam S, et al. Anti-PD-1 therapy in patients with advanced melanoma and preexisting autoimmune disorders or major toxicity with ipilimumab. Ann Oncol. 2017 Feb 1;28(2):368–376.

- Arbour KC, Mezquita L, Long N, et al. Impact of baseline steroids on efficacy of programmed cell death-1 and programmed death-ligand 1 blockade in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Oct 1;36(28):2872–2878.

- Faje AT, Lawrence D, Flaherty K, et al. High-dose glucocorticoids for the treatment of ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis is associated with reduced survival in patients with melanoma. Cancer. 2018 Sep 15;124(18):3706–3714.

- Wang Y, Abu-Sbeih H, Mao E, et al. Immune-checkpoint inhibitor-induced diarrhea and colitis in patients with advanced malignancies: retrospective review at MD Anderson. J Immunother Cancer. 2018 May 11;6(1):37.

- Perez-Ruiz E, Minute L, Otano I, et al. Prophylactic TNF blockade uncouples efficacy and toxicity in dual CTLA-4 and PD-1 immunotherapy. Nature. 2019 May;569(7756):428–432.

- Verheijden RJ, May AM, Blank CU, et al. Association of anti-TNF with decreased survival in steroid refractory ipilimumab and anti-PD1-treated patients in the Dutch melanoma treatment registry. Clin Cancer Res. 2020 May 1;26(9):2268–2274.

- Chan KK, Tirpack A, Vitone G, et al. Higher checkpoint inhibitor arthritis disease activity may be associated with cancer progression: Results from an observational registry. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020 Oct;2(10):595–604.

- Santini FC, Rizvi H, Plodkowski AJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of re-treating with immunotherapy after immune-related adverse events in patients with NSCLC. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018 Sep;6(9):1093–1099.

- Simonaggio A, Michot JM, Voisin AL, et al. Evaluation of readministration of immune checkpoint inhibitors after immune-related adverse events in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Sep 1;5(9):1310–1317.