Image Credit: Stepan Kapl/shutterstock.com

SAN FRANCISCO—Let’s say your radiologist comes to you and says that an angiogram gives a diagnosis of CNS vasculitis on four patients, all with acute onset of headache and stroke: One is a 25-year-old woman who is three months pregnant. Another is a 50-year-old man using excessive doses of nasal decongestants. Another is a 40-year-old woman with uncontrolled migraines. And then there’s a 30-year-old man who snorts cocaine.

There’s a problem here, said Julius Birnbaum, MD, MHS, assistant professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins, who is board certified in both rheumatology and neurology: “These patients do not have clinical features which are typical of CNS [central nervous system] angiitis.” Instead, he said, they likely have reversible vasoconstriction syndrome (RVCS), in which the underlying pathophysiology is a vasospasm, not vasculitis.

The unreliability of angiogram diagnoses was one of the points Dr. Birnbaum emphasized in his talk on rheumatic diseases that are manifest in the central nervous system, part of a clinical review course held at the 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting. He discussed primary angiitis of the CNS (PACNS), CNS syndromes in neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NPSLE) and demyelinating syndromes in Sjögren’s syndrome (SS).

PACNS

Dr. Birnbaum

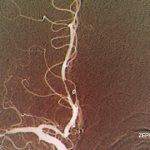

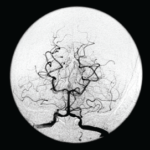

Angiograms, Dr. Birnbaum said, are “notoriously non-specific,” and the same signs “can be seen in a plethora of non-inflammatory vasculopathies.”

“Every time your radiologist says that they’ve done an angiogram [that] is diagnostic of a CNS angiitis, your first step should be to assume the diagnosis of a primary angiitis is incorrect,” he said. Instead, investigation of other mimics should be pursued, he advised.

Angiograms for PACNS and RVCS look similar, but the key is that the angiograms in RVCS can reverse to normal within three months. Treatment for RVCS is not an immunosuppressant, but calcium channel blockers with glucocorticoids as an adjunct, not for immunosuppression, but to help with the vasospasm, Dr. Birnbaum said.

Other mimics of PACNS include amyloid angiopathy, often seen in the context of patients older than 65 or with lobar hemorrhage; CNS atherosclerosis; and a cardioembolic source, such as infective endocarditis, which might be signaled by strokes with a multi-vessel distribution.

Four key components of a PACNS diagnosis are an abnormal brain MRI, seen in 90% of cases; inflammatory lumbar puncture, which is also seen in 90%; an abnormal CNS angiogram, seen in 50–90% of cases; and brain biopsy, which carries a 50–75% sensitivity and 60% specificity. Having four of those, it has been proposed, represents a “definite” PACNS diagnosis, and three is “probable.”