Image Credit: Stepan Kapl/shutterstock.com

SAN FRANCISCO—Let’s say your radiologist comes to you and says that an angiogram gives a diagnosis of CNS vasculitis on four patients, all with acute onset of headache and stroke: One is a 25-year-old woman who is three months pregnant. Another is a 50-year-old man using excessive doses of nasal decongestants. Another is a 40-year-old woman with uncontrolled migraines. And then there’s a 30-year-old man who snorts cocaine.

There’s a problem here, said Julius Birnbaum, MD, MHS, assistant professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins, who is board certified in both rheumatology and neurology: “These patients do not have clinical features which are typical of CNS [central nervous system] angiitis.” Instead, he said, they likely have reversible vasoconstriction syndrome (RVCS), in which the underlying pathophysiology is a vasospasm, not vasculitis.

The unreliability of angiogram diagnoses was one of the points Dr. Birnbaum emphasized in his talk on rheumatic diseases that are manifest in the central nervous system, part of a clinical review course held at the 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting. He discussed primary angiitis of the CNS (PACNS), CNS syndromes in neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NPSLE) and demyelinating syndromes in Sjögren’s syndrome (SS).

PACNS

Dr. Birnbaum

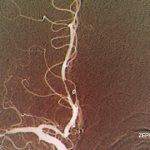

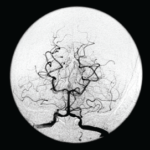

Angiograms, Dr. Birnbaum said, are “notoriously non-specific,” and the same signs “can be seen in a plethora of non-inflammatory vasculopathies.”

“Every time your radiologist says that they’ve done an angiogram [that] is diagnostic of a CNS angiitis, your first step should be to assume the diagnosis of a primary angiitis is incorrect,” he said. Instead, investigation of other mimics should be pursued, he advised.

Angiograms for PACNS and RVCS look similar, but the key is that the angiograms in RVCS can reverse to normal within three months. Treatment for RVCS is not an immunosuppressant, but calcium channel blockers with glucocorticoids as an adjunct, not for immunosuppression, but to help with the vasospasm, Dr. Birnbaum said.

Other mimics of PACNS include amyloid angiopathy, often seen in the context of patients older than 65 or with lobar hemorrhage; CNS atherosclerosis; and a cardioembolic source, such as infective endocarditis, which might be signaled by strokes with a multi-vessel distribution.

Four key components of a PACNS diagnosis are an abnormal brain MRI, seen in 90% of cases; inflammatory lumbar puncture, which is also seen in 90%; an abnormal CNS angiogram, seen in 50–90% of cases; and brain biopsy, which carries a 50–75% sensitivity and 60% specificity. Having four of those, it has been proposed, represents a “definite” PACNS diagnosis, and three is “probable.”

The brain biopsy is “particularly important,” Dr. Birnbaum said.

“The role of a brain biopsy is not only to secure the diagnosis of a primary angiitis of the central nervous system, but also potentially uncover occult CNS mimics,” he said.

CNS Syndromes in NPSLE

Dr. Birnbaum described a three-step process for diagnosis and treatment of NPSLE: identifying whether a CNS syndrome is due to SLE or another co-morbidity; defining the spectrum of the syndrome; and understanding when to use immunosuppressive treatment rather than symptomatic treatment.

A key point, he said, is to “always suspect that, when you have a lupus patient presenting with neurological complications, that neurological disease is not attributable to lupus.” Up to 40% of SLE patients will have a CNS syndrome not due to SLE.1 It’s important to be aware of the “lurking possibility of an infection,” he said.

“The differential diagnosis can be vast,” he said. “You can formulate a very, very comprehensive differential diagnosis using a mnemonic called VITAMIN.” This, he joked, was a distillation of three years of neurology residency into one slide.

VITAMIN

- Vascular/stroke: These include septic emboli, subarachnoid hemorrhage from mycotic aneurysms, septic thrombophlebitis;

- Infections: These should be classified as bacterial, fungal or viral source and by anatomic region, whether parenchymal, meningeal or vascular;

- Traumatic: This just means the experience is traumatic for the patient and is not very relevant to the diagnosis, Dr. Birnbaum said;

- Autoimmune or inflammatory syndromes;

- Metabolic: This includes derangements from renal insufficiency or posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES);

- Iatrogenic: Complications, potentially from corticosteroid or immunosuppressive therapy; and

- Neoplastic causes.

He hammered home the point that “none of these causes, obviously, from competing co-morbidities, require immunosuppressive therapy.”

Once competing co-morbidities are excluded, the clinician has to assess whether the syndrome is seen more frequently in lupus than in non-SLE controls, he said. Headache, mood disorders, anxiety disorder and mild cognitive impairment are syndromes seen with similar frequency within lupus and without, and can be dealt with as though the patient does not have lupus. Treatment should not include immunosuppressants, Dr. Birnbaum said.

Once a syndrome is actually determined to be neuropsychiatric SLE, the clinician has to decide whether to use immunosuppressants.

But, he said, in the absence of extra-neurological activity, immunosuppressants are rarely warranted—not in the case of cerebrovascular disease, which is seen in 5–15% of SLE patients; not for seizures presenting later into the SLE course, with seizures seen in 5–20%; not in cognitive impairment, seen in up to 80% of SLE patients; and usually not in psychosis, which is seen in up to 5% of patients.

SLE myelitis is the only example that calls for immunosuppression. In gray matter myelitis—characterized by an irreversible flaccid paraplegia that comes on very quickly—corticosteroids can be given in the prodromal period, otherwise they won’t work, Dr. Birnbaum said. In white matter myelitis—which comes with milder weakness and is relapsing—immunosuppressive therapy is called for, he said.

Demyelinating Syndrome in Sjögren’s Syndrome

Again, Dr. Birnbaum advised clinicians to be skeptical, even when an MRI suggests a demyelinating syndrome in SS. There must be clinical evidence, such as optic neuritis, myelitis or brainstem syndrome, he said.

“It’s not enough to have vague neurological complaints,” Dr. Birnbaum said. “If your Sjögren’s patient does not have a demyelinating syndrome, no matter what the MRI is showing, it’s very unlikely the patient has an underlying demyelinating disease.”

Two potential candidates for an underlying demyelinating disease are neuromyelitis optica (NMO) and multiple sclerosis (MS).

In MS, spinal cord inflammation comes in a transverse pattern; however, it’s longitudinal in NMO; the clinical features of MS are initially sensory with mild motor weakness, and in NMO there is greater weakness; there are no autoantibody markers for MS, but NMO is marked by the NMO-IgG antibody. And MS treatment typically involves immunomodulatory medication, and NMO calls for immunosuppressants.2

In recent years, about half of Sjögren’s patients were defined as having NMO, but there have been only sparse reports of MS in Sjögren’s, he said. Most of the literature on MS as a Sjögren’s complication was published before NMO was recognized as its own entity.

He noted that the aquaporin 4 protein—antibodies to which (NMO-IgG) are a marker of NMO—is enriched in the end organs targeted in Sjögren’s.

“It really, really suggests that neuromyelitis optica, and not multiple sclerosis, is the salient demyelinating syndrome seen in Sjögren’s,” he said. “And further study is warranted to see whether this is a causative relationship.”

Second Chance

If you missed this session, it’s not too late. Catch it on SessionSelect

Thomas R. Collins is a medical writer based in Florida.

References

- Hanly JG, McCurdy G, Fougere L, et al. Neuropsychiatric events in systemic lupus erythematosus: attribution and clinical significance. J Rheumatol. 2004 Nov;31(11):2156–2162.

- Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pitock SJ, et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2006 May 23;66(10):1485–1489.