PHILADELPHIA—Health disparities, as defined by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, are “preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or opportunities to achieve optimal health that are experienced by socially disadvantaged populations.”1 Addressing health disparities is challenging and demands creative research approaches that directly solicit insight and feedback from affected patient populations.

At ACR Convergence 2022, Cheryl Barnabe, MD, MSc, FRCPC, professor of medicine and community health sciences, University of Calgary Cumming School of Medicine, Alberta, Canada, and Leanne Te Karu, MH, Department of General Practice, University of Auckland, New Zealand, provided examples of how community-engaged research has guided improvements in rheumatic disease care delivery to Indigenous populations with rheumatoid arthritis and gout.

Background

About 5% of the global population (370 million people) identify as being part of an Indigenous community, “distinct social and cultural groups that share collective ancestral ties to the land and natural resources where they live, occupy or from which they have been displaced.”2 These communities are particularly affected by health disparities. For example, across North America, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affects two to three times as many Indigenous people as it does people in the general population, and Indigenous people with RA have a higher burden of disease.3,4

Accessible RA Care in Canada

Dr. Barnabe took care to note that this discrepancy is not solely attributable to lack of access. Data from the Canadian Early Arthritis Cohort (CATCH) confirmed that even when early optimal RA care was delivered, a huge discrepancy still exists in the odds of achieving a Disease Activity Score-28 (DAS28) remission, with someone who identifies as Indigenous having 61% lower odds (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.38, 95% confidence interval 0.25–0.62).5

Why might this be? The answer isn’t simple. Dr. Barnabe explained, “At the patient level, arthritis is a very significant issue. But it exists within the social context in which they’re living, a high burden of other comorbidities which may take precedence, and sometimes prior experiences of racism that make it so that they don’t come for arthritis care.”

As they started to think about how to address health disparities in RA, Dr. Barnabe and colleagues realized their current triage system was making it harder for patients to see rheumatologists. For example, referrals and lab requirements barred many from evaluation. In response, they started a rheumatology self-referral clinic within a primary care clinic.

They ran this model in two locations. Dr. Barnabe shared, “We saw a significant [number] of people with inflammatory arthritis [who] hadn’t ever been referred, despite these models functioning in parallel with typical referral systems. There were also several who hadn’t received care in many years, but when they heard about the clinic they were willing to return to care.”

Patients in the self-referral clinic were followed for several years. Dr. Barnabe explained, “Over time, pain, function and patient global assessments actually didn’t improve and were trending toward worse. So we went back to the patients and asked them what we could do better.” The general response was something like this: “You’re not considering all the things that I need to support my health—spiritual, emotional and mental support that are part of holistic well-being.”

In response, the team focused on identifying other factors affecting patients’ health and livelihood, such as obtaining appropriate housing and accessing adjunctive arthritis services (e.g., physical and occupational therapy). With the Indigenous community, the team co-developed a new “patient care facilitator model of care, termed arthritis liaison, to support culturally relevant patient-centered care plans.” The arthritis liaison was a person from the Indigenous community who “served as a bridge between clinicians and patients, and fostered continuity, helping patients receive coordinated care within the community.” The model was valued by both patients and care providers.6

Dr. Barnabe looks forward to further data that will permit continued tailoring of interventions to best help these communities. “Partnership, trust and active reflection are what’s needed to best help these communities,” she concluded.7

Accessible Gout Care in New Zealand

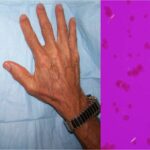

Ms. Te Karu spoke about her work to improve health equity in Indigenous patients with gout in New Zealand. The prevalence of gout in New Zealand is high. “We have the dubious honor of being a gout hotspot of the world,” she said. In the Indigenous Maori population, gout may develop as early as the second decade of life, and the prevalence rises to as high as 45–50% by age 80 in men, and 25–30% by age 80 in women.8 This is considered an undercount.

As in other parts of the world, gout in New Zealand isn’t well-managed. Only 56–59% of patients in New Zealand with gout are dispensed urate-lowering therapy (ULT), with only 36–44% receiving regular dispensing.9

“This is a good demonstration of equity vs. equality,” Ms. Te Karu commented. Nearly equivalent percentages of patients (whether Maori, Pasifika or non-Maori/Pasifika) were dispensed ULT, but if you consider that prevalence is three to seven times higher among Indigenous populations, something very apparent comes out of this data.”

To improve health equity, Ms. Te Karu sought to optimize gout medication therapy via a multi-layered initiative that included community meetings, a decision support tool embedded in the practice management system, staff education, community health worker involvement, nurse standing orders, point-of-care urate testing, evening clinics and community-developed health literacy resources.

“I incorrectly thought that gout was low-hanging fruit,” she shared.

Access was a focal point of the initiative. More than half of patients had limited or no access during clinic open hours, and an additional 20% had transport/disability access issues. Ms. Te Karu shared personal examples from patients to illustrate her point. “One man had a history of drunk driving for which he was incarcerated in his 20s, so job security was a particularly important issue for him. Others worked 13-hour days as laborers,” she said.

To conclude, Ms. Te Karu spoke to the importance of acknowledging that the phenotype of gout is different among Indigenous populations that may have a higher prevalence of risk factors for the development of gout. “It’s so important that we don’t have a workforce who judges people and thinks the default is around lifestyle or food intake,” she said. “That’s crucial to how we move forward.”

Samantha C. Shapiro, MD, is the executive editor of Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. As a clinician educator, she practices telerheumatology and writes for both medical and lay audiences.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health disparities. Last reviewed 2020 Nov 4. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/disparities/index.htm.

- The World Bank. Indigenous peoples. Last updated 2022 Apr 14. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/indigenouspeoples.

- McDougall C, Hurd K, Barnabe C. Systematic review of rheumatic disease epidemiology in the Indigenous populations of Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017 Apr;46(5):675–686.

- Hurd K, Barnabe C. Systematic review of rheumatic disease phenotypes and outcomes in the Indigenous populations of Canada, the USA, Australia and New Zealand. Rheumatol Int. 2017 Apr;37(4):503–521.

- Nagaraj S, Barnabe C, Schieir O, et al. Early rheumatoid arthritis presentation, treatment, and outcomes in Aboriginal patients in Canada: A Canadian early arthritis cohort study analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018 Aug;70(8):1245–1250.

- Umaefulam V, Loyola-Sanchez A, Chief VB, et al. At-a-glance—Arthritis liaison: A First Nations community-based patient care facilitator. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2021 Jun;41(6):194–198.

- Lin CY, Loyola-Sanchez A, Boyling E, et al. Community engagement approaches for Indigenous health research: Recommendations based on an integrative review. BMJ Open. 2020 Nov 27;10(11):e039736.

- Winnard D, Wright C, Taylor WJ, et al. National prevalence of gout derived from administrative health data in Aotearoa New Zealand. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012 May;51(5):901–909.

- Health Quality & Safety Commission New Zealand. Atlas of Healthcare Variation. Gout. https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/our-data/atlas-of-healthcare-variation/gout/.