Rheumatologists have growing concerns about how we manage rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and the disease outcomes we are achieving.1 Over the past two years, clinician rheumatologists have begun working together to address these problems through the Rheumatoid Arthritis Practice Performance (RAPP) Project, a nationwide clinical quality-improvement initiative. The RAPP Project has now grown to 168 participants managing more than 80,000 RA patients. We will describe the problems RAPP clinicians have identified within our current RA management and highlight several high-impact improvements we are testing and implementing.

Disease Registry

When the RAPP Project initially asked its participants how many RA patients they manage, what percentages of their RA population have active disease or controlled disease and what percentage are overdue for intended office visits, they had no answers. When they then began using a simple disease registry to manage their RA populations as part of this quality-improvement project, most identified many more RA patients than they had imagined. They also learned that the frequencies of their assessments for patients with controlled, low, moderate and high disease activity fell far short of those recommended by the Treat-to-Target Task Force, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR).2-4 Evidence of these disease assessment gaps was presented at the 2014 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting (see Figure 1).5,6

(Click for larger image)

Figure 1: Multi-biomarker assessment data from the aggregated populations of 44 RAPP Project rheumatology practices: Unassessed and overdue patients.

Treat-to-Target RA Management under Current Practice Models

The population management registries of RAPP Project participants have documented that assessing RA disease activity during physician office visits creates an unmanageable workload. We not only lack the visit capacity to see, assess and manage our RA patient populations at the recommended frequencies, but we are also unable to consistently do all the necessary work ourselves for individual patients during these scheduled visits.

Consider the evidence. RAPP Project practices have, on average, 585 RA patients per rheumatologist full-time equivalent (range 67–1,800), representing about 40% of the established patients seen in a typical week.5 Practices with mid-level providers predictably manage more patients per rheumatologist, but experience similar visit capacity issues.

The Treat-to-Target Task Force recommends assessing patients with moderate and high disease activity monthly, and those with controlled and low disease activity every three to six months.2 Many RAPP clinicians feel it’s appropriate to perform assessments at intervals of three months for patients with moderate or high disease activity and six months for those with controlled or low disease activity, allowing that some patients will be scheduled more or less frequently as their needs require. Yet even with these more lenient disease assessment frequencies, our median percentage overdue for the moderate and high cohort is 66% and for the controlled and low cohort is 52%.6 Moreover, these percentages overdue remain stable from month to month within individual practices, despite RAPP physicians fully intending to perform assessments at every scheduled visit and having access to lists of overdue patients from our registries.

Many of us initially saw these persistent performance gaps as either our own individual failure or as a failure on the part of our patients to keep scheduled appointments. To systems analysts, however, these persisting gaps instead suggest a classic systems capacity bottleneck in which available resources (in this case visit slots) are too few to allow timely performance of required work (in this case disease activity assessments) at the recommended intervals.7 This visit capacity bottleneck causes a stalemate wherein the number of patients reassessed each month is equal to the number that become overdue. In any business, meeting basic customer needs is fundamental to success; our registry data suggest that we are not achieving this standard in our RA management.

Population management enables clinicians to provide timely disease activity measurement & recommended care.

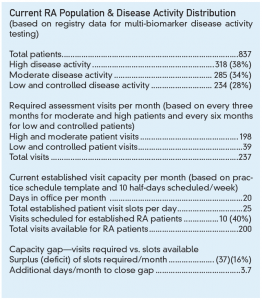

This problem was confirmed by more detailed capacity analyses of 20 RAPP Project practices (see Figure 2, for an example). The magnitude of the visit capacity bottleneck among these practices is influenced by RA population numbers, days practiced per month, numbers of patients scheduled per day, percentage of visits allocated to managing established RA patients, and finally distribution of disease activity in the disease population. When physicians schedule additional out-of-office activities, our capacity bottleneck worsens. Simply put, this bottleneck compromises our RA disease assessments and management—and we were all blind to the problem until we analyzed the data from our population management registries.

(Click for larger image)

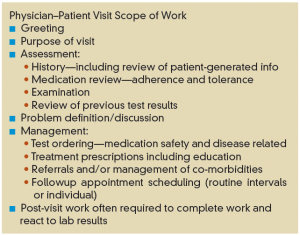

Figure 3: Typical scope of work associated with an RA established patient visit.

The evidence for time constraints during individual visits is equally sobering. The time scheduled, typically 20 minutes, is generally insufficient for the physician to perform all the necessary work (see Figure 3). The infrequent use of composite disease activity assessments by RAPP physicians and other rheumatologists is due at least in part to the lack of time available to perform them.5 However, scheduling longer visits just worsens the bottleneck, and, too often, an urgent patient need trumps the intended disease assessment and management.

The Visit Capacity Bottleneck Is a System-Design Problem

Once RAPP clinicians realized that working harder wouldn’t help close our care gaps, we were faced with four seemingly stark options: 1) accept our current performance as being the best we can do; 2) severely reduce our patient panel sizes to fit available provider appointment slots; 3) add additional rheumatologists to our practices; or 4) change how we assess RA disease activity and who does it.

For most rheumatologists and patients, the first two options are nonstarters. The third option is fraught with obstacles, including a shortage of rheumatologists in many locales.8 Most RAPP clinicians now agree that the fourth option, changing how we assess disease activity, is a breakthrough opportunity for improving our efficiency, costs and quality of care.

What is clear to us is that population management is the key to resolving the visit capacity bottleneck. Evidence for this has been generated by exemplar practices in other medical specialties that also manage chronic diseases in diverse practice environments.9 Population management enables clinicians to provide timely disease activity measurement and recommended care. It requires adopting better-defined systems of care that include:

- Disease registries to track required work, performance and disease outcomes;

- Clinical workflow standardization and care algorithms;

- Standardized disease activity measures; and

- A team approach within health systems and practices.

Of the 168 busy rheumatology practices participating in the RAPP Project, about 90 to date are implementing population-management capabilities, and the number continues to grow as clinicians are able to resolve practice- and system-level barriers.

To begin, we are each fully enrolling our RA population into a disease registry and subsequently identifying all of our patients who are overdue for disease activity assessments. Then to further address the bottleneck, many of us are reorganizing our practice care teams and assessments in innovative ways. Here are a few examples:

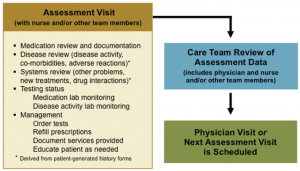

- Some practices are scheduling assessment visits with nurses and/or mid-level providers at least two weeks before physician visits to collect each physician’s preferred disease activity data and medication safety data (see Figure 4). These visits provide a more complete, consistent and well-organized dataset for the physician-patient encounter.

- Based on these disease activity data, rheumatologists, mid-level providers, and nurses are determining at the point of service who will see which patients. Physicians focus on more complex patients, other team members provide care for established patients with less complicated needs, and the practice’s total visit capacity increases significantly.

- In fact, once this division of effort is implemented, some physicians are hiring additional mid-level providers to right size their teams.

- Once a patient’s lab results are returned (see first bullet above), some care teams are reviewing their assessment visit data and deciding whether the patient requires a provider visit at all. Patients with well-controlled RA and no other problems are being rescheduled instead for a future assessment visit. This is freeing physician visit slots, enabling the physician to promptly see patients with high disease activity and other pressing management needs. (These reviews can be completed in batches rather than one patient at a time.)

- Embedding a pharmacist as an additional provider within the practice team is one highly intriguing option being implemented by some RAPP physicians. By managing medications, solving medication-related problems, and educating patients the pharmacist further reduces the physician’s workload.

As a result of these improvements, RAPP practices are beginning to report positive revenue impacts through an increase in visits and other services that address previously unmet patient needs. Moreover, some are adding technician-performed ultrasound and other clinical and educational services as individual patients require.

Removing the Physician Visit Bottleneck Enables Treat-to-Target Care

Many RAPP physicians, our practice teams, and most importantly our RA patients are enthusiastic about the benefits population management is providing for care and disease outcomes. We are now able to say with confidence, “My team manages this number of RA patients, their assessments are up to date, their treatments are necessary and safe, and their disease activity reflects the best we can possibly do for them.”

Drs. Erin Arnold, William Arnold, Conaway, Crump, LaCour, Mossell, Parris, Thomas, Sikes and Winkler are clinician rheumatologists participating in the RAPP Project. Dr. Harrington and Mr. Bower are partners in Joiner Associates LLC, the RAPP Project coordinator.

Disclosure Statement

Joiner Associates received consulting fees from Crescendo Bioscience for designing and coordinating the project—without any influence from the company. Crescendo Bioscience has also provided support for participant advisory board meetings for this quality-improvement initiative. The participating clinician authors have reported no other individual disclosures.

References

- Harrold LR, Harrington JT, Curtis JR, et al. Prescribing practices in a US cohort of rheumatoid arthritis patients before and after publication of the American College of Rheumatology treatment recommendations. Arthritis Rheum. 2012:64(3);630–638.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: Recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631–637.

- Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, et al. 2012 Update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs ad biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:625–639.

- Smolen JS, Landwew R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573.

- Sikes D, Crump G, Thomas K, et al. Population management of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in rheumatology practices: A quality improvement project. Arthritis Rheumatol: Abstract Supplement. 2014;66(11):S596.

- Winkler A, Mossell J, MacLaughlin E, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) disease activity assessment and population management processes used by clinician rheumatologists. Arthritis Rheumatol: Abstract Supplement. 2014;66(11):S594.

- Koster MBM de. Capacity Oriented Analysis and Design of Production Systems. Ed. Beckmann M, Krelle W. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 1989.

- Deal CL, Hooker R, Harrington T, et al. The United States rheumatology workforce: Supply and demand, 2005–2025. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Mar;56(3):722–729.

- Harrington JT, Newman ED. Great Health Care: Making It Happen. Ed. Harrington JT, Newman ED. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media, 2012.