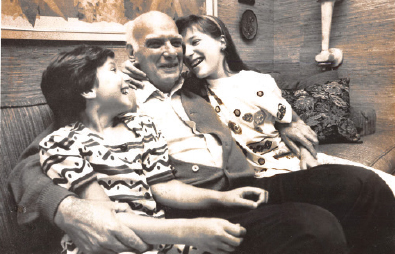

James Rosenbaum, MD, has medicine in the genes: His dad, two brothers, his wife and his daughters—both of them—are doctors.

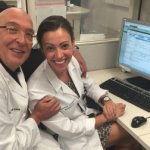

Why medicine? Curiosity, mostly. Dr. Rosenbaum is still wide-eyed to learn, whether it’s in his post as chair of the Division of Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), or as chief of ophthalmology at Legacy Devers Eye Institute, both in Portland, Ore.

He has a unique combination of talents: He’s the only practicing rheumatologist in the world to head a department of ophthalmology. He developed an interest in ophthalmology some 35 years ago when, as a fellow trying to develop a rat model of reactive arthritis, a pathologist told him rats had developed uveitis.

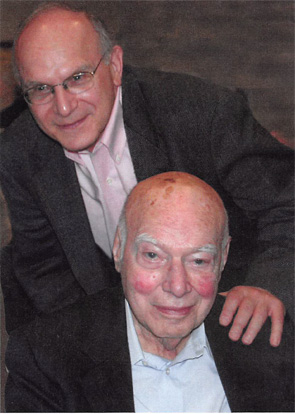

His passion comes from his father, Edward Rosenbaum, MD—the first rheumatologist in Oregon and, later, the author of A Taste of My Own Medicine, a memoir that served as the basis for the screenplay of the 1991 Disney film, The Doctor. Dr. Rosenbaum’s chair is named for his father, who built OHSU’s rheumatology division.

Dr. Rosenbaum’s passion for medicine is something he clearly passed on to his two daughters—Lisa, a cardiologist and noted author who has written for The New England Journal of Medicine, The New Yorker and The New York Times, and Jennifer, who is still choosing a specialty. Dr. Rosenbaum’s wife, Sandra, is a cardiologist.

Dr. Rosenbaum recently talked to The Rheumatologist about his career:

The Conversation

The Rheumatologist: As a kid, did you think you wanted to be a rheumatologist?

Dr. Rosenbaum: Becoming a doctor was sort of the path of least resistance. My parents had four sons, and my dad would take us on rounds. And it was clear that everyone adored him. So he never said to us, ‘Gee, you ought to be a doctor,’ or ‘This is a wonderful life.’ What he showed was that he derived a tremendous amount of gratification from taking care of people. And so my older brother’s a doctor, I’m a doctor, my younger brother’s a doctor, and the black sheep became a lawyer.

TR: You blazed your own trail in combining two specialties. Why have you continued your focus for so many years?

Dr. Rosenbaum: Science doesn’t resolve questions; it finds answers that allow you a platform to ask additional questions. So the more that I discovered or that others discovered about the model that I stumbled on, the more unresolved issues were raised. And that still remains true today. Science is a lot like working on any kind of puzzle—a crossword puzzle, a Sudoku—but you don’t just turn to the answer in tomorrow’s paper, which makes it sometimes more frustrating, but all the more satisfying if you can gain a piece of the resolution.

TR: Over the years, has the endless loop left you frustrated or satisfied, a little of both? Do you still have that same quest to answer more questions?

Dr. Rosenbaum: I don’t think I’ve lost the curiosity. Maybe a little bit of the vigor, but I’m still asking questions. Often, one of the most difficult questions in the lab is knowing when to give up. Nothing ever quite succeeds as planned, and you keep revising and revising, and at some point you think, ‘Well, we just don’t have the tools or the reagents or the insight to answer this question.’ And you kind of put it aside, and then five years later, a decade later or 15 years later, someone’s made some sort of seminal discovery that relates to what you were doing, and you can approach it in a whole new light.

My dad would take us on rounds. What he showed was that he derived a tremendous amount of gratification from taking care of people.

TR: Fifteen years is a long time to wait for payoff. How do you do it?

Dr. Rosenbaum: You keep inching along. You make little small observations, but they’re not necessarily paradigm shifts. So you’re munching away, but every once in a while something happens, and it really makes you see the world in a different light.

TR: It’s difficult enough to keep up with the news and literature in just one set of journals, let alone the time to do two specialties. How do you keep current?

Dr. Rosenbaum: I think each of us is just a little fraudulent. As an ophthalmologist, I have deficiencies, but I have been very fortunate to have talented fellows and faculty members who could help me. And as a rheumatologist, I’m probably not the guy you want to have inject the small joint of your hand. But if you’ve got a patient who’s got an eye inflammation and who’s got a swollen joint, I’m definitely the person you want to discuss the problem with.

TR: What did you set out to accomplish in your career?

Dr. Rosenbaum: I’m not sure that I formulated it. I think there’s a part of my dad’s book that states, ‘I made a house call, and I helped someone out, and then I got paid for it. What could be greater? You do some good, and you’re financially rewarded for it. How can you beat that?’ So I see taking care of patients as a really gratifying way to help someone’s life, and I see research as a way to help multiple people instead of doing it on an individual basis.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.