Toward the end of the conference, I met with Sharad Lakhanpal, MBBS, MD (past president of ACR), and David Daikh, MD, PhD (current ACR president), who were visiting India for the annual rheumatology conference. We also went bird watching in the forest beside the hospital. I had an enjoyable discussion with both of them regarding the future of rheumatology care.

Getting Started

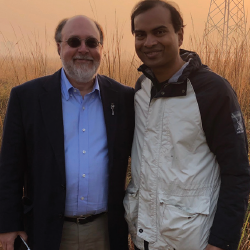

Dr. Bhatt (right) went bird watching on the Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences campus with ACR President David Daikh, MD, PhD.

On arrival at SGPIMS, I was greeted by a very pleasant rheumatology fellow. My living arrangements had been prearranged. My transition was seamless. During the first week, I rotated through the outpatient department, inpatient floors and the ultrasound clinic.

I was very impressed by the fellows’ fund of knowledge. One of them even knew all the authors’ names for Harrison’s Rheumatology chapters. The fellows practice both adult and pediatric rheumatology, and have a good fund of knowledge in infectious diseases, as well. Infectious diseases often mimic rheumatologic disease in that part of the world. The fellows also rotate through the immunology lab and, as a result, have a good knowledge of diagnostic tests.

Rheumatology in India is a three-year fellowship instead of the two years in the U.S. and involves extensive rotations in pediatric rheumatology, as well as immunology. The fellows have to be virtually top of the line to make it into rheumatology, because it is highly selective.

The Care

India has an enormous population and very few doctors. The patient volume tends to be high, but the waiting period for patients is only one day, and patients can come in as walk-ins at SGPIMS. Currently, the patient volumes are 3,500–3,600 patients a month in outpatient clinics and about 140–150 patients a month in the inpatient setting. This is counterbalanced by less onerous documentation requirements in India. Using electronic medical records, as is typical in the U.S, takes valuable face-to-face time away from patient care.

Dr. Bhatt (right) went bird watching on the Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences campus with ACR President David Daikh, MD, PhD.

I had the chance to observe direct patient care with no computer barriers. Each patient maintains a personal diary. This is updated at every patient encounter and serves as a portable medical record.

The patient care is value driven, because of limited resources. In India, doctors don’t run tests merely because they are available. Justification must be made before further tests can be ordered.