In November 2017, I went to Lucknow, India, where I would spend my time as an exchange fellow at the Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences (SGPIMS) as part of the ACR International Visiting Fellows Exchange Program.

Where I Come From

I completed my medical degree at Mahatma Gandhi Missions Medical College, Navi Mumbai in Mumbai, India, and emigrated to the U.S. in 2000. I completed a residency in internal medicine at Mt. Sinai in New York in 2004. After graduation and over the past 15 years, I practiced in six states, and I have had exposure to different practice settings. During my residency and while working as a hospitalist, I saw the practice of medicine transition from direct patient care to an over-reliance on technology.

Zoran Milic / SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

I found that I enjoy following and taking ownership for my patients’ care over the long term, and I was increasingly concerned about the fragmentation of care. I decided to pursue a rheumatology fellowship because I was fascinated by the tremendous advancements in this field. I completed my fellowship (Louisiana State University, Shreveport) in July 2017 and started working as a community rheumatologist in Richland, Wash.

Dr. Bhatt attended the 33rd Annual Conference of the Indian Rheumatology Association, hosted by the Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences in Lucknow, India.

During my fellowship, I learned about the ACR’s International Visiting Fellows Exchange Program, which allows fellows to rotate to rheumatology practices in different countries. I applied for the ACR exchange program to India during my fellowship. When I learned I had been selected to participate in the Exchange Program, my first thought was that I wanted to see how medicine in India has changed since I left it 20 years ago.

Going Back to India

After the 2017 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting in San Diego, where I met the Indian rheumatology team, I traveled to India. Usually the exchange happens in October, but I went later so that my trip would coincide with the annual Indian Rheumatology Association conference. The conference was held from Nov. 30–Dec. 3, 2017, at SGPIMS.

At the annual Indian Rheumatology Association conference, I was impressed by the doctors trying to do registry studies and research within the most resource-limited settings. I attended the ultrasound course at the conference. Education in India is more affordable than in the U.S.: the ultrasound course cost just $100. The ACR also had a presence at the conference.

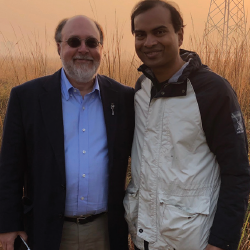

Toward the end of the conference, I met with Sharad Lakhanpal, MBBS, MD (past president of ACR), and David Daikh, MD, PhD (current ACR president), who were visiting India for the annual rheumatology conference. We also went bird watching in the forest beside the hospital. I had an enjoyable discussion with both of them regarding the future of rheumatology care.

Getting Started

Dr. Bhatt (right) went bird watching on the Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences campus with ACR President David Daikh, MD, PhD.

On arrival at SGPIMS, I was greeted by a very pleasant rheumatology fellow. My living arrangements had been prearranged. My transition was seamless. During the first week, I rotated through the outpatient department, inpatient floors and the ultrasound clinic.

I was very impressed by the fellows’ fund of knowledge. One of them even knew all the authors’ names for Harrison’s Rheumatology chapters. The fellows practice both adult and pediatric rheumatology, and have a good fund of knowledge in infectious diseases, as well. Infectious diseases often mimic rheumatologic disease in that part of the world. The fellows also rotate through the immunology lab and, as a result, have a good knowledge of diagnostic tests.

Rheumatology in India is a three-year fellowship instead of the two years in the U.S. and involves extensive rotations in pediatric rheumatology, as well as immunology. The fellows have to be virtually top of the line to make it into rheumatology, because it is highly selective.

The Care

India has an enormous population and very few doctors. The patient volume tends to be high, but the waiting period for patients is only one day, and patients can come in as walk-ins at SGPIMS. Currently, the patient volumes are 3,500–3,600 patients a month in outpatient clinics and about 140–150 patients a month in the inpatient setting. This is counterbalanced by less onerous documentation requirements in India. Using electronic medical records, as is typical in the U.S, takes valuable face-to-face time away from patient care.

Dr. Bhatt (right) went bird watching on the Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences campus with ACR President David Daikh, MD, PhD.

I had the chance to observe direct patient care with no computer barriers. Each patient maintains a personal diary. This is updated at every patient encounter and serves as a portable medical record.

The patient care is value driven, because of limited resources. In India, doctors don’t run tests merely because they are available. Justification must be made before further tests can be ordered.

The doctors have a wide repertoire of knowledge, not only because they see pediatric rheumatology cases as well as adult, but also because the patients come in with a wide variety of diseases. Infectious diseases are very common. Because India’s population is very large, rheumatology fellows have a good chance of seeing rare diseases as well. I saw two to three vasculitis patients a day. To put this in perspective, I had seen about seven active vasculitis cases during the course of my entire fellowship.

The doctors talk to the patients about spiritual and religious beliefs, because that is a big factor in patients’ compliance with modern medications. They also instruct patients on basic physical therapy.

I was also very impressed with the telemedicine services. SGPIMS does a lot of telemedicine outreach for rural areas and also has periodic medical vans reach out to patients in the community.

There is good face-to-face collaboration between fellows and different departments. I had a chance to observe the doctors’ lounge, which has long since disappeared in most of our U.S.-based hospitals, having been replaced by in-basket messaging within the electronic medical record.

Once a month, rheumatology fellows meet with fellows from a neighboring institution for dinner to discuss interesting cases. It was very encouraging to see not only interdisciplinary collaboration, but also collaboration within the same discipline from different institutions.

SGPIMS has taken the concept of doctor wellness to a whole new level. The 400 acre campus on the outskirts of the city is home to 200 species of birds that are found nowhere else in India. There is an emphasis on coexisting with nature. There are excellent sports facilities for doctors, including swimming pools and tennis courts.

Challenges in India

Healthcare issues that India has tackled very well: Generics in India are very affordable; biosimilars have made inroads. There is no pay for delay that makes long-standing drugs ever more costly in the U.S. Methotrexate and plaquenil are affordable; therefore, triple therapy is optimized before resorting to biologics.

Biologics and biosimilars are also much cheaper in India and affordable to the middle class. A few examples of price points: secukinumab costs less than $2,000 a year; apremilast, $20 a month.

Dr. Bhatt performs a bedside musculoskeletal ultrasound.

Dr. Bhatt (left side, striped shirt) and the Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences rheumatology fellows at a farewell dinner.

Dr. Bhatt and the rheumatology fellows were treated to a local puppet show at his farewell dinner.

The Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences rheumatology fellows, Dr. Bhatt (front row in the striped shirt), as well as Professor of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology Able Lawrence, MBBS, MD, DM, and Latika Gupta, MBBS, MD, DM, the ACR/IRA exchange fellow from India to the U.S.

India has a very good patient-support program for certain biologics. Nurses make home visits and fax records to the primary care doctor or the rheumatologist at different time points.

India does have several issues hindering rheumatology care. From the medication standpoint: Although generics are inexpensive, a substantial proportion of patients cannot afford them. Biologics are also cheaper than in the U.S., but a substantial proportion of patients cannot afford them, either. I was distressed to see several patients with spondyloarthropathy unable to afford even cheaper biosimilars and ending up being on NSAIDs chronically, with no options, in spite of concomitant heart or kidney disease. Those conditions would have contraindicated such treatment here in the U.S.

From the provider standpoint: There are only 30 rheumatology training positions in India for a population that is four times the size of the U.S. At SGPIMS itself, 50 students apply annually for four positions. As a result, many doctors do not qualify for training spots, although they might be completely capable of providing excellent care. Due to economics and an inability to hire labor, the fellows spend unnecessary time performing administrative duties instead of clinical, such as calling patients when beds are free or physically performing routine lab tests.

From the patient standpoint: Patients may take alternative medicines for many years and suffer progressive joint deformities before seeing a rheumatologist in person. With no clear enforcement of regulations, anyone can practice quackery. Patients may encounter a physician (who may not be a rheumatologist) prescribing long-term steroids or a “snake oil salesman” who never graduated from high school.

Rheumatologists do not have an advocacy committee, and politics plays a major role in deciding institutional and rheumatology care (more so than in the U.S.). Political attitudes can change on a whim; as a result, you have constructions and medical projects that were started with good intentions but have been stalled.

Back Home in the U.S.

I came home from India with lasting friendships and memories, in addition to a unique educational, cultural and personal experience. I saw rare rheumatologic diseases that I otherwise would probably have seen only once in a lifetime. It is fascinating to explore the practice of medicine in a completely different environment.

The exchange also has given me an entirely new perspective into international health. I would highly encourage current fellows to apply for the ACR International Visiting Fellows Exchange Program.

I plan to implement the following into my own practice:

- Resist technology’s interference with direct patient care. Optimize my EMR so I can spend more face-to-face time with patients.

- Try to understand patients’ spiritual and religious beliefs.

- Ask patients about alternative medications and encourage an open discussion.

- Remember the primary reason I entered medicine and practice empathy.

- Interact more with colleagues, have face-to-face discussions, share down time and foster in-person friendships. Have a collaborative attitude, rather than a competitive attitude.

- Seek help with patient care, if needed, and be curious and open. Always feel free to consult with other colleagues in case of a diagnostic dilemma.

- Continually evaluate myself for self-improvement and knowledge advancement.

- Take time to devote to personal interests including family and hobbies to prevent burnout.

Rajat Bhatt, MD, completed his rheumatology fellowship in 2018 and is board certified in both rheumatology and internal medicine. He is now a community rheumatologist with Providence Health Systems/Kadlec Medical Center, Richland, Wash.