John P. Atkinson, MD, is a great detective. But instead of solving murder mysteries, he unravels the mysteries behind diseases—diagnosing them, understanding their origin or cause, and identifying effective treatments.

As director of the rheumatology division at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo., Dr. Atkinson is also the Samuel B. Grant Professor of Medicine. It’s his lab work that has kept him active in the field of medicine at age 71 and that earned him the Human Immunology Research Award from the American Association of Immunologists in 2012. The lifetime achievement award recognizes his “significant and sustained contributions to the understanding of immune processes underlying human disease pathogenesis, prevention and therapy.”

“I like to do research because I want to figure out the cause of human disease,” says Dr. Atkinson. “I’m very interested in the basic science of what drives inflammation, as well as trying to suppress it in patients. Rare diseases that lead to inflammation are very exciting to me.”

Studying Birds, Then Human Proteins

While growing up in Kansas, Dr. Atkinson had no plans of being a physician or medical researcher. As an active athlete, he attended the Kansas University (KU) on a basketball scholarship. But at 6’3″, he wasn’t quite tall enough to go pro. He says “big time” basketball eluded him (“I wasn’t good enough”), so he pursued a different career mainly due to a “remarkable” fifth grade teacher who taught him and his classmates how to identify the birds and trees of Kansas. Identifying rare birds or, in one case, a new bird (i.e., the pine grosbeak) for the state list became a passion, just behind sports.

From that point on, he became an avid ornithologist (i.e., a bird watcher) and planned on obtaining a doctoral degree in the field. But when a colleague passed away from Hodgkin’s disease, his focus changed, and he enrolled in medical school, graduating from KU in 1969.

His medical journey was just beginning. Focused on becoming an allergist, he served as an intern and assistant resident at Massachusetts General Hospital between 1969 and 1971. For the next three years, he worked at the National Institutes of Health, Laboratory of Clinical Investigation, dealing with many rare diseases that were rheumatology based, such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis. It was that job that piqued his interest in becoming a clinical immunologist. Then in 1974, he went to Washington University for a two-year postdoctoral research fellowship.

“Upon my arrival at then Barnes Hospital as an Allergy and Clinical Immunology Fellow, the program was short on rheumatology fellows, so I filled in,” he says. “In those old days, immunologists were becoming directors of many of the rheumatology programs in the country, [because] it was discovered that immune phenomena mediated many types of rheumatic diseases. Many of us were, thus, appointed heads of rheumatology divisions.”

He’s stayed put ever since.

During his career, he has trained more than 70 predoctoral students and postdoctoral fellows from not only the U.S., but also England, Thailand, Germany, India and China. He says many have since accepted independent research positions and launched distinguished careers in academia, government, or the biotechnology or pharmaceutical industries. He takes significant pride in their accomplishments, which is the ultimate reward for any good teacher.

However, Dr. Atkinson’s own career is just as impressive. He started out as an immunologist/cell biologist and then evolved to biologic chemistry, molecular biology and molecular genetics to study how the complement system functions in health and human disease.

His medical, teaching and research honors are too numerous to list, but the Arthritis Foundation honored him in 2012 as a Research/Medical Hero. In 2009, he received the Thai-American Physicians Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award, and he received Master distinction from the ACR in 2008.

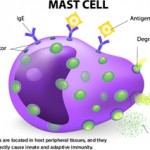

Regulatory Proteins

Dr. Atkinson’s joy, his passion, is studying the structure, function and genetics of human and mouse complement receptors regulatory proteins. Over the past decade, researchers in his lab have focused on defining the functional consequences of rare variants in regulators in human diseases (atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and age-related macular degeneration), along with characterizing virulence factors synthesized by poxviruses and flaviviruses that modulate the host’s complement system.

“Fellows in the laboratory discovered several novel proteins in the 1980s, and then they cloned them in the 1990s, but we had to wait until we had the power of human genetics to find out what diseases these proteins were actually involved in,” Dr. Atkinson says. “Most of the [diseases] we and others had considered were wrong, [which] came as quite a surprise to us. We would have never looked. Now, we have identified common and rare genetic variants in diseases in which the proteins we worked on in the ’80s and ’90s are predisposing.

“Over the years, we have helped identify several new rare diseases—thanks to very bright graduate students and postdoctoral fellows—including a vasculopathy caused by the DNase TREX1 that mimics a systemic rheumatic disease,” says Dr. Atkinson.

More Excitement Than Ever

After 45 years of conducting research, Dr. Atkinson’s appetite for discovering the unknown hasn’t shrunk a bit. Neither has his love of sports: He recently stopped playing basketball only because he couldn’t find an “over 70” league.

With no plans to retire anytime soon, he will continue doing targeted, deep sequencing to find the cause of more diseases.

“Thanks to modern genetics, we are now more easily able to figure out human diseases,” says Dr. Atkinson. “This is the major reason I’m still active. It’s more exciting than ever to be a basic and translational scientist than at any time in my career.”

Carol Patton is a freelance writer based in Las Vegas, Nev., and writes the Rheum after 5 column for The Rheumatologist.