Dr. Kahlenberg and her son, Adyn, enjoy a huge sweet potato harvest.

How are Annie and Abby?

That’s a question some patients ask J. Michelle Kahlenberg, MD, PhD, a rheumatologist and assistant professor in the school of medicine at the University of Michigan, who also runs a lupus research lab at the University of Michigan Health System. Patients aren’t asking about her children, but family members of another kind.

Since 2010, Dr. Kahlenberg and her husband have owned and managed a nearly 80 acre farm on the outskirts of Ann Arbor, Mich., which grows organic vegetables and is inhabited by free-range cattle, chickens, sheep and pigs. Annie and Abby are the 450 lb. resident sows.

Dr. Kahlenberg’s husband, Mark, who holds a master’s degree in environmental science and worked for the Western Reserve Land Conservancy in Cleveland, manages the farm and performs most of the grunt work. Still, Dr. Kahlenberg spends many evenings, weekends and even some of her vacation time tending to her large organic garden and farm animals. Despite the early morning hours and physical labor involved, she says the experience is a respite from the stressful encounters from her job as a physician-scientist—and helps her recapture her childhood. She grew up on a farm.

Planting Her Feet on the Ground

After graduating medical school and obtaining her MD and PhD in 2006 at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Dr. Kahlenberg completed her internal medicine residency at University Hospitals of Cleveland. In 2009, her young family—which by now included a 3-year-old son, Adyn, and 6-month-old daughter, Emerson—moved to Ann Arbor for her rheumatology fellowship.

“We were trying to figure out our life plans,” Dr. Kahlenberg says. “We talked a lot about how we wanted to live on a farm, so we bought a semi-working farm that had been involved in various types of operations since the 1800s but wasn’t in the best of shape. It required a lot of work to get things functional.”

Since then, Dr. Kahlenberg has devoted most of her personal time to her four-legged patients and organic vegetable garden. Each spring, she spends two weeks of vacation time planting her garden from dawn until dusk. Throughout the year, she also vaccinates the farm animals and stitches them up as needed. She says she learned on the fly, from YouTube, which demonstrates various techniques, from animal birthing to insemination.

Dr. Kahlenberg and her daughter, Emerson, collecting eggs. They get 80 every day.

Although an animal lover, much of her satisfaction comes from her garden, which includes heirloom tomatoes, garlic, potatoes, onions, sweet corn, different types of squash, beets, kale, chard, and basil and other herbs. The whole idea, she says, is to grow and sell a wide variety of vegetables that people can use to create fresh, healthy and interesting meals.

She describes a typical summer weekend that could be the focus of a Norman Rockwell painting: On Saturday, she and her husband wake up at 6 a.m. to pick vegetables that he sells that day at the nearby farmer’s market, and then they eat breakfast with their children. For the rest of the day, Dr. Kahlenberg tends her garden, doing everything from weeding to planting to moving crops. When her husband returns around 4 p.m., she helps him unload the truck and feed the wilted greens to the pigs and chickens.

On Sundays, the farm is open to visitors. Children can hold baby chicks and pet sheep while their parents scout out which vegetables they want to buy and serve for dinner.

During the winter months, the farm is less busy. Most of her time is spent delivering and vaccinating “our babies,” she says, mainly referring to piglets, lambs and calves.

Teaching Lessons, Trading Stories

The farm is an active and lively home for 24 sheep, five cows, two steer, 80 chickens that lay eggs, 200 others referred to as “meat” chickens, 11 pigs, including a large black hog who’s an endangered farm animal, and—during summer—20 turkeys, not to mention five barn cats and the family dog, Emma, an English Shepherd.

“You start to learn the personalities of the animals,” says Dr. Kahlenberg. “We keep the breeding animals for a long time and give them names. Although you don’t want to get cuddly with a 600 lb. sow; that would be dangerous.”

She believes the farm is a master teacher, especially for her young children. They’re not only learning responsibility, but also compassion, she says, explaining that it’s a farmer’s job to provide animals being raised for meat with a healthy and happy life before they end up on the dinner table.

Likewise, it’s important to purchase quality food—without antibiotics—for farm animals, which is very costly. She points to a truckload of quality feed for pigs. The month’s supply is almost equivalent to a mortgage payment—approximately $1,000.

“Operating a small farm like ours is not easily financially viable without one person working outside the home,” she says.

Relishing the fruits of her labor, Dr. Kahlenberg carves home-grown pumpkins with her children.

Dr. Kahlenberg takes pleasure in the views and the cows.

Happy as pigs on pasture.

Unpredictable weather can also be costly by damaging crops—and lower backs. Back in 2012, she says it didn’t rain from roughly May to mid-August. Since the vegetable garden isn’t set up with a costly drip irrigation system, Dr. Kahlenberg recalls watering each plant for 10 seconds by hand several times a week. As the weeks passed, the farm’s well, which supplies water to the house, barn and garden, was running dry.

Still, she was determined not to lose any plants. So she saved the family’s bath water. Every night, she bucketed five gallons at a time, carrying it downstairs and across the backyard to the garden to water less crucial vegetables, like pumpkins.

While the drought tested her resolve as a farmer, she says farming is also her salvation, both as an individual and physician.

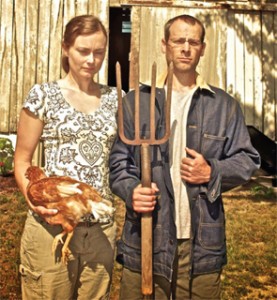

Dr. Kahlenberg and her husband, Mark Skowronski, run an organic vegetable and pasture-raised meat farm.

“What surprises me is the satisfaction that I get from farming,” she says. “As a kid, my parents would tell me to go weed the garden, which ended up being a chore. But the peace and stress relief I get now from dirtying my hands and doing physical labor is really something that I love. That was a pleasant surprise.”

It also helps build better patient–doctor relationships. Visiting a renowned academic medical center, such as the University of Michigan, can be intimidating for rural patients, she says. But when they realize their doctor is also a farmer, it seems to ease some of their anxiety. More likely than not, they end up swapping stories about farm life.

Many patients ask about the animals and seem happy to address something else other than their condition.

“It really gives me a way to communicate with people besides talking about their diseases,” she says. “Patients enjoy that—getting to know their physician in a way they can relate to.”

Carol Patton, a freelance writer based in Las Vegas, Nev., writes the Rheum after 5 column for The Rheumatologist.