At the beginning of 2013, Kathleen Ferrell planted an idea in the mind of her husband, Rick Brasington, MD. Ms. Ferrell is the past president of the St. Louis Herb Society and a master gardener at the Missouri Botanical Garden, and she wanted to make honey from the lavender plants in their herb garden.

There was just one key ingredient missing: bees.

One conversation led to another, and Dr. Brasington, a rheumatologist and fellowship program director at Washington University in St. Louis, found himself attending several meetings sponsored by the Eastern Missouri Beekeepers Association. He received a crash course on beekeeping, spoke with others in the profession, read at least 10 books on the subject and became so intrigued with the bee culture that by April, the couple had become beekeepers.

Since then, Dr. Brasington says his learning curve has shot straight up. Despite getting stung several times—once to the point where his right arm became swollen from his elbow to his knuckles—he says bees are basically docile creatures and don’t like to be disturbed. They’re simply too busy working.

Getting Started

The barrier to entry for beekeeping is not only thick skin, but roughly $1,000 for protective gear, equipment and a nucleus of bees, called “nucs,” which is a colony of bees with its own queen and baby bees that are incubating, all prepared by another beekeeper.

Dr. Brasington explains that the process of making honey rests on the wings of the colony’s queen bee.

When the queen makes her virgin flight, drones, or male bees, fertilize her in mid-air. She may mate with up to 10 drones in sequence. After they inseminate her, they pull away, fall to the ground and die. A good queen can lay 1,500 eggs a day.

“The male bees are pretty useless,” Dr. Brasington says. “All they do is inseminate the queen and fall over dead. It’s up to the females to take care of things. The males just can’t be counted on to get things done.”

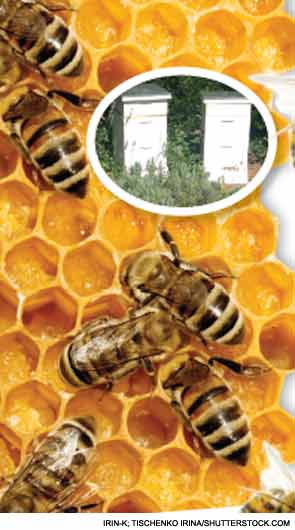

Dr. Brasington describes man-made beehives as white, wooden structures that resemble a filing cabinet with hanging files. Each structure usually contains 10 wooden frames that are vertically dropped inside the structure. Bees build a honeycomb in the middle of each frame, which supports a wax or plastic foundation. The cells in the honeycomb are used for rearing young bees and storing honey.

The first level of the structure houses the bees. The second contains the frames, which are full of honey that bees consume during the winter months. Above that are smaller boxes, referred to as supers, which also store additional honey that can be harvested by the beekeeper.

He says the whole point of being a beekeeper is to help raise a huge colony of bees. During the spring and summer months, when flowers bloom, he explains that beekeepers want an army of bees to gather enough nectar to help them get through the winter months. Bees fan their wings to dehydrate the nectar until it’s composed of 18% water or less. Once it reaches that concentration, it will not ferment, which is why honey can last a long time without refrigeration.

But the bees that make the honey won’t live long enough to eat it, he says. Worker bees only live between six and eight weeks. It’s the welfare bees, those that live during the winter months, that consume it.

“It’s fascinating that the bees manage to do all this stuff without anybody telling them, without having any wars or killing anybody,” he says. “They just do it.”

Long-Term Hobby

So far, Dr. Brasington says one colony is doing great. However, during the first year, he says bees usually don’t produce enough honey to harvest.

He says a beekeeper’s job is minimal. Nothing is required on a daily basis. But every week, he mixes 12 pounds of sugar into 1 gallon of water, then places the syrup into the hives. To prevent the bees from drowning in the syrup, he created rafts or floats made out of chopsticks tied together.

Even better, no work is required during winter. When the temperature drops to 45 degrees, he won’t open their hive to prevent heat from escaping. Cold temperatures will kill bees.

Dr. Brasington’s goal is to keep his bees alive through the winter. Then, if all goes well, he will feed the bees in the spring and fall, let nature take its course when the flowers bloom, allowing the bees to gather nectar, and then harvest the honey in the fall.

Up to now, he has spent more time reading about beekeeping than actually doing it. On average, he only spends several hours each week on his newfound hobby. The hardest part of the job, he says, is figuring out which beekeepers offer the best advice.

“Like physicians, beekeepers can be very opinionated about how to do things,” he says. “Different beekeepers will tell you absolutely opposite things about the same subject. So you have to somehow make your own decisions about which way you’re going to go, because there are a lot of ways to do this.”

At the very least, he says this latest obsession makes for great conversation. When guests come over, Dr. Brasington doesn’t hesitate to don his protective suit, show them the hives and take out the frames.

“They’re absolutely fascinated,” says Dr. Brasington. “It’s a great party trick.”

Listen to excerpts of our interview with Dr. Brasington.

Carol Patton writes the Rheum after 5 column for The Rheumatologist.