Image Credit: Richard Bowden/shutterstock.com

I am a few weeks post-retirement. Having written thank you notes and completed urgent home projects, I swing in a hammock at our currently fire-threatened cabin north of Winthrop, Wash., and reflect.

I feel like a young boy while freely flipping pages of a hand-scribed picture book, The Principles of Uncertainty, by Maira Kalman. She begins the book, “How can I tell you everything that is in my heart?” She offers stories from history, her travels and family, then pauses and observes, “My brain is exploding. Trying to make sense … What can I tell you? The realization that we are all (you, me) going to die and the attending disbelief—isn’t that the premise of everything? It stops me dead in my tracks.”

I think of my 40 years in medicine—Alabama, England, public health, health services research, health plan medical director, international clinic and travel volunteer, internal medicine and rheumatology practice—then stop the swing as my last day comes into focus with activated senses.

The more I think about the day, the more I savor what had been so good for so long, but then I wonder what a similar day will look like in 10 years. How will healthcare reform, large data computing, social media and transformative technologies change the day?

Cases in Point

We learn from our patients and colleagues, and then find the evidence that supports our gestalt. Here are several stories from my last day and the questions they raise:

Alice (a longtime patient) sends me an e-mail from Yellowstone as she heads east for graduate art school. I wrote her a letter to help her obtain financial support. The day before, Alice had left a painting for me of a Siberian man, whose big smile was activated only because she asked if she could take his photograph. Due to her juvenile inflammatory arthritis and pleuritis, autoimmune polyendocrinopathy, myasthenia gravis and immune deficiency syndrome, she had never thought she would be stable enough to go back to school. I was hopeful and now smile as I think of two of the many bullets she has dodged: Although she didn’t meet guidelines, we had won a long rituximab preauthorization appeal and were hopeful for remission: Anakinra, cyclosporine, mycophenolate, IVIG and prednisone had only reduced her recurring flares. Prior to that, she was hospitalized for a week because an emergency room nurse didn’t believe in patient-centered care. While being evaluated for pneumonia, Alice quietly noted, “I can feel my myasthenia flaring. Here, in my purse, is the medicine I need.” The power-centered nurse discounted Alice’s self-assessment. Alice stopped breathing and spent the next week in the ICU.

Does true patient-centered care support self-diagnosis and treatment? How did evidence-based guidelines kidnap and hold hostage true patient-centered, personalized care? What patients say and believe are of equal importance to patient-centered care as their genetic make-up is to personalized care. Care cannot be recommended based on a population average. How are we going reestablish ourselves with our patient as the first and last arbiter of patient-centered, personalized care decisions?

Just before lunch, I see Sue, who has been my patient since she transitioned from the pediatric clinic, 35 years ago. She lost function in her right shoulder and arm strength several weeks ago—greater than can be explained by her ultrasound-proven, completely torn rotator cuff. An MRI of her previously fused neck is planned for this afternoon. As we say our final, emotion-laced goodbyes, she utters those words that have terrorized many physicians, “By the way, one more thing.” She shows me forearm lesions—two red, nodular areas about each about 3×1″, one medially and the other laterally. A no-charge, ‘part of my exam’ ultrasound, showed only swollen fat tissue and normal muscle. My semi-retired brain draws a blank, so I use one of my shout-outs to interrupt my esteemed partner, Julie Carkin, MD.

Armed with her subconscious awareness that history is 90% of the diagnosis, Julie carefully examines Sue and then comes to the question, “Sue, have you been trimming roses recently?” Sue hesitates and then confirms the likelihood that is my first case of sporotrichosis.

Will the future system revalue the diagnostic utility of her astute history and exam that prevented an MRI? How will the system break the trend of increasing physician dissatisfaction in order to attract and support the best docs and staff who are willing to Choose Wisely, by listening to and looking at patients, rather than perform procedures and diagnostics?

During lunch, I take a picture with my necktie-wearing staff, who acknowledge my daily uniform of Snoopy, smiley face, Road Runner and Mickey Mouse ties. I am interrupted by a phone call from a pain doc at the university, who acknowledges my retirement letter and thanks me. She appreciates our integrated-care approach (dietician and counselor on staff) and my focus on recurrent inflammation in many of her chronic pain patients.

Will rheumatology contribute its full potential in solving our chronic pain epidemic? What are the unique or valued contributions we can make?

After lunch, I see 22-year-old Grant and his parents for the first follow-up visit to summarize a transition plan. Although closed to new patients for some time, I had seen him as a favor to a friend. Grant’s chronic fatigue of five years started with a very stressful freshman year in college. Although recent tests from a non-accredited laboratory raised his parents’ hope of a chronic Lyme diagnosis, I focus on his recurring GI symptoms, mild abdominal tenderness and recently elevated CRP. I discuss how the gut and the immune system are interrelated, the work our dietician has done with food sensitivities, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and the paper about serotonin modulation of the immune system.1 I tell Grant how hard small intestinal inflammatory illnesses are to diagnose, but that medication trials might be of diagnostic/therapeutic utility. I also explain how the combined effects of low-dose antidepressant medications, quality sleep and self-care activities will be important to balancing his immune system. He brightens as I make clear this is not “just in your head” and feels hopeful as I lay out a plan.

How do we help these patients with poorly understood illnesses find hope? What are the new clinical tools and systems that will help us assess and modulate factors affecting immune system imbalance?

Stormy drove more than 200 miles to be my official last patient in the mid-afternoon. She brought me handmade, embroidered and personalized snack pouches for every rider on TeamOverman, who would soon be cycling the People’s Coast Classic the length of Oregon in support of the Arthritis Foundation.2 This visit is to be a time for stories and hugs, but her pre-visit questionnaire shows major dysfunction on the RAPID questionnaire, and her pain is 10/10. She limps, and her left forefoot is swollen. Neither X-ray nor ultrasound confirms her self-diagnosis of a stress fracture. Ultrasound demonstrates a swollen, inflamed metatarsal-cuneiform joint directly in the area of tenderness. After a bupivacaine and triamcinolone injection, she walks across the room without pain.

In 10 years, will ultrasound be used by all rheumatologists? Will this be done by her primary physician and interpreted via a telemed visit, saving her the painful three-hour drive?

[Patients with musculoskeletal disorders] invite new innovations in patient-centered, comprehensive, conservative care services.

I finally catch up with the very active listserv that is focused on the frustrations of time-consuming Medicare documentation requirements, the costs of preauthorization advocacy and the strategies for fighting or working with big insurance companies. We are burdened by complex patients, required data elements for each moderately complex patient (a listserv math major calculates 5,376) and healthcare administrators who discount physicians. Members are encouraged to support the ACR advocacy efforts, to form super groups, to diversify away from the infusion business and to take responsibility for self-regulation. As an example of such efforts, Howard Kenney, MD, describes how the Washington Rheumatology Alliance, under the leadership of Jeff Peterson, MD, has launched a Rheumatology Medical Home Demonstration Project to work with insurers and primary care physicians to “refine our delivery of rheumatic disease care within a rheumatology care model.”3

What is the “rheumatology care model,” and will it meet the needs of an evolving healthcare system focused on value? What collaborations are you building for the future?

That evening, I toast my nurse, Claudia, and all our patients who want to stay with her and her new doctor. In the words of the Arthritis Foundation (AF) and its new brand, our nurses are the champions of yes. “Yes, I care; yes, I will get your refills; yes, I understand how stressed you are; yes, I will get you the answers; yes, I will get you worked in; yes, we will appeal the denial; and yes, I am here for you.”

What do we need to champion now for the future? Will our teams change? Will the ACR and AF need to rejoin forces to be a more effective voice for doctor and patient together?

As you reflect on these stories and similar ones from your current day, think of your rheumatology model of care and if/how you see it evolving. Might the following ideas be found in your future rheumatology care model?

- Care contacts that move away from physician office schedules to on-demand care at their place of work or via the Internet;

- Care management that tracks patient performance and facilitates movement along a comprehensive, personalized care plan;

- Individualized programs that support your patients’ emotional, physical, social and spiritual concerns and conditions;

- Care extenders that reach out to individuals at risk of musculoskeletal morbidity; and

- New care strategies that reduce costs.

What Is the Current Rheumatology Care Model?

Rheumatologists work in a variety of settings, such as solo, single-specialty group and multi-specialty group practices. However, common characteristics of rheumatologists and our practices do exist.

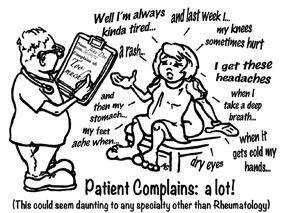

We are a patient-centered specialty. We take care of complex patients with multiple symptoms and multiple-organ involvement that dramatically affect their lives. Few algorithms exist for integrating all the factors we use to make care decisions. I was once told that a rheumatologist knows when he/she has trained successfully when they can look patients in the eye all day long and comfortably say, “I don’t know.”

We are mostly a referral specialty, with our patient population defined by referring providers and our clinical interests and availability. For years, a rheumatology badge of honor has been how much we are needed, symbolized by our long new-patient wait times. Given these access/demand issues, some practices have closed to patients with fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue—or limited the number of such patients they will see. There are few financial or system incentives to see complex, time-consuming patients, although they are common in most practices. Even for classic inflammatory disease patients, there are frequent delays between onsets of symptoms and treatment initiation.4

Pain management is part of rheumatology care, but there is wide variation in how often opioids are prescribed, behavioral care is offered and self-management coached. Localized musculoskeletal problems, even when there is joint swelling and signs of inflammation, commonly are first seen by orthopedists due to PCP referral patterns and lack of rheumatology availability.

Businesses are demanding greater value for their healthcare expenditures, in ways that will help employees be healthier & more productive, & miss work less often.

Infusion-therapy units are now common components of rheumatology practices because they offer patients convenience, rheumatologist oversight and a profitable ancillary service line. Pharmaceutical companies have a high profile in many offices by supporting the preauthorization coordinator, the nurse educators and the samples program. Many practices offer pharmaceutical research studies, and many clinicians take part in company advisory panels or speaking bureaus.

Clinical information systems vary widely, and for most practices, the outcomes have not yet met expectations and hopes.5 The ACR has facilitated the development of registries, and individual rheumatologists and electronic health record companies have created systems individualized for rheumatologists’ practices.6

Forces That May Effect Change

New healthcare organizations, such as accountable care organizations (ACOs), are being formed as strategies to move our system toward three goals formulated by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), also known as Triple Aim: Improve the patient experience of care (including satisfaction and quality), improve the health of populations and reduce the per capita cost of healthcare.7,8 You may be in an ACO now or are aware of ones developing around you. ACOs are incentivized to lower per capita costs, but still pay physicians on a fee-for-service or salary basis.

Businesses are demanding greater value for their healthcare expenditures, in ways that will help employees be healthier and more productive, and miss work less often. Consultants, such as Mercer, offer white papers, such as Taking Total Health Management (THM) to a New Level, which lists six best practices for companies: data-driven solutions, engagement-focused strategies, clinically focused care management, supportive work environment, integration among functions and resources (medical, health and wellness, safety, risk management), evaluation and continuous improvement.9

Under clinically focused care management, THM needs to deal with the critical needs of the chronically ill, who account for the majority of employer expenses. Holistic care management will require cross-functional care teams experienced in motivational coaching; offer individuals the behavioral and social support they need; address emerging health issues, such as stress and sleep; and offer telemedicine and onsite health services.

Currently, insurance companies offer care or disease management support for their beneficiaries separate from and without coordination with our office systems. Each individual insurance company assists only its insured patients. Their programs are not available to other patients in our office and may actually compete with office-based programs. These disparate, external efforts by multiple insurance companies can work against our practice’s efforts at building our own care-management systems, which would be available to all of our patients. What if each insurance company and each pharmaceutical company that interfaced with your office contributed to a care-management and education program fund in your office so that you could offer these uncompensated services to all of your patients in an unbranded way?

Edward H. Wagner, MD, MPH, developed a model for chronic illness called the Chronic Care Model (CCM). The CCM was important to the development of the Primary Care Medical Home (PCMH) and the Patient-Centered Specialty Practice (PCSP).10,11 The CCM identifies the essential elements of healthcare that encourage high-quality chronic disease care: the community, the health system, self-management support, delivery system design, decision support and clinical information systems.12

The PCMH, also called patient-centered primary medical homes, has five attributes:

- Comprehensive care: PCMH is accountable for meeting the large majority of each patient’s physical and mental healthcare needs, including prevention and wellness, acute care and chronic care. Providing comprehensive care requires a team of care providers. This team might include physicians, advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, nurses, pharmacists, nutritionists, social workers, educators and care coordinators;

- Patient centered: The PCMH focuses on the whole person, understanding and respecting each patient’s unique needs, culture, values and preferences, and supports patients in learning to manage and organize their own care;

- Coordinated care: The PCMH coordinates care across specialty care, hospitals, home healthcare, community and transition-of-care support services;

- Accessible services: The PCMH delivers accessible services with shorter waiting times for urgent needs, enhanced in-person hours, around-the-clock telephone or electronic access to a member of the care team and alternative methods of communication, such as e-mail and telephone care; and

- Quality and safety: The PCMH demonstrates a commitment to quality and quality improvement via ongoing engagement in such activities as using evidence-based medicine and clinical decision-support tools to guide shared decision making with patients and families, engaging in performance measurement and improvement, measuring and responding to patient experiences and patient satisfaction, and practicing population health management.

For specialty physicians, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) now has recognition requirements to become a PCSP:

- Track and coordinate referrals with other specialists and PCPs to coordinate testing and care of shared patients;

- Provide access and communication via timely appointments, telephone and secure electronic messages during and after office hours, and training team members to be patient centered;

- Identify and coordinate patient populations by capturing key clinical and administrative data to facilitate reporting on specific populations, using evidence-based tools to manage care for those populations and providing follow-up when care is needed;

- Create and manage a patient-centered care plan that includes patients’ medications and referrals to educational resources and community services;

- Track and coordinate care, such as hospital transitions, lab, imaging and other specialty referrals with other practices from the point of request through receipt and patient notification; and

- Improve performance by measuring clinical processes, outcomes and patient experience, showing improvement over time and demonstrating transparency by sharing data within the practice and with external organizations.

Currently, most rheumatology practices are influenced by the community and healthcare system they are in but do not incorporate such models into their practices. However, the Washington Rheumatology Alliance demonstration project is moving in this direction.

What if you designed & offered a two-month musculoskeletal consultation & care package for patients being considered for surgery or expensive spine procedures?

Increasing Musculoskeletal Population & Costs

In the future, rheumatologists’ value to the system and compensation will likely correlate with the contribution they make to the organization’s overall success. If success is the Triple Aim, then we will need to help optimize patient satisfaction and quality of care, help attain the highest level of musculoskeletal health for the population in question and help reduce the per capita musculoskeletal expenditures.

What will it take? We will first need to be able to identify and evaluate the population.

Currently, our populations are those patients who come into the clinic. Possible populations around which data might be collected and evaluated are: all PCP office populations in your referral network; all employees of a single or several businesses; all enrollees in a closed-model ACO or HMO; and all people in a geographic community.

From a community perspective, Lawrence et al reported in 2008 that an estimated 27 million Americans had osteoarthritis, 3 million had gout, 5 million had fibromyalgia, 59 million and 30 million had back pain and neck pain, respectively, in the prior three months.13

From a business perspective, musculoskeletal disorders are associated with high absenteeism, lost productivity and increased healthcare, disability and worker’s compensation costs.14 Worker’s compensation care management has led to the development of physician medical and treatment guidelines, which are specific about objective parameters that must be met to proceed with MRI diagnostics, spine injections and a variety of surgeries.15 One usual criterion to be met before authorizing a procedure or surgery is “failure of conservative care,” but there is little specificity as to what that means other than duration of care. This population invites new innovations in patient-centered, comprehensive, conservative care services.

A Premera medical director recently stated that there are three areas for Triple Aim focus: oncology care, cardiovascular care and musculoskeletal care. Richard A. Deyo, MD, MPH, reported that spine-related expenditures increased substantially from 1997 to 2005, without corresponding improvement in self-assessed health status.16 The cost of total knee arthroplasty and spine fusion surgery each tripled during these years. Musculoskeletal complaints account for over 30% of primary care visits.17

Costs of arthritis care have skyrocketed with dramatic increases in some generic drugs and the pervasive high costs of biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Many factors affect a patient’s financial bottom line, including basic coverage, deductibles, donut holes, co-pays and pharmaceutical support programs. The updated Arthritis Foundation website offers in-depth support for patients regarding healthcare costs and pharmaceutical support programs.18 The Rheumatologist has reviewed these issues.19 Drug pricing is outside the control of our practices, but therapy selection is not. Our choices are being scrutinized not only from the perspective of the public good and the cost to health plans, but more commonly by our patients with large deductibles.20

Why Rheumatology?

This brings me back to my last day. The stories of Alice, Sue, Grant, Stormy, Claudia, Drs. Carkin, Peterson and Kenney, and all the patients who need us to be their champions of yes prime me to give you the 10 reasons why I think rheumatologists are best suited to lead the changes needed to meet the challenges of attaining the three aims for a population with musculoskeletal illness risks and care needs.

Our nurses are the champions of yes. ‘Yes, I care; yes, I will get your refills; yes, I understand how stressed you are; yes, I will get you the answers; yes, I will get you worked in; yes, we will appeal the denial; & yes, I am here for you.’

How many times have you heard, “I saw a dozen doctors and multiple therapists before getting in to see you”? How frequently have you seen individuals who have run the gauntlet of spine injections and surgery before getting their spondyloarthritis syndrome diagnosed? How many arthroscopies and MRIs are still done before anyone considers inflammatory synovitis? How many X-ray reports state “degenerative joint or disc disease,” suggesting this is an aging or wear-and-tear process, rather than an arthritic condition?

Letterman is gone, so I won’t give my 10 in reverse order. Rheumatologists are prepared to lead the way because they:

- Are great docs: Dr. Carkin reminds me that rheumatologists are the best at history taking and pattern recognition—patterns that don’t show up on imaging studies, but when identified will reduce the use of diagnostic tests and procedures.

- Are collegial: Sue reminds me that a problem too tough for one rheumatologist may not be too tough for two. Because we associate with other greater clinicians and aren’t afraid to ask, building networks of excellence won’t be difficult.

- Understand complexity: Alice reminds me that we take care of some of the most complicated, costly patients in outpatient medicine. Are you adequately compensated for all of the elements of decision making and care you provide for such patients?

- Have a need to be accountable: Grant reminds me that many undiagnosed patients need access to our care. Only by committing to a system of population management may we ensure this happens.

- Understand inflammation in disease: Stormy’s 10/10 pain reminds me of the extreme pain that inflammatory chemicals create. Rheumatologists’ understanding and treatment can be of high value in settings where others treat only what they can see (i.e., anatomic abnormalities—acute lumbago pain [possible discitis], acute post-op rotator cuff surgical pain [possible post-inflammatory sensitization], knee sprain ‘meniscus’ pain [possible inflammation and sensitization], acute TMJ pain [possible arthritis], sacroiliac dysfunction pain [possible sacroiliitis], forefoot degenerative joint disease pain [possible inflammatory arthritis], post-op swelling and pain possible [possible acute pseudogout] or “fibro flare” pain [possible enthesitis/bursitis]).

- Understand multifactorial illness models: Grant reminds me that stress, the microbiome and the environment may trigger inflammatory disorders, and inflammatory disorders can be associated with metabolic problems, possibly causing weight gain, sleep apnea, chronic fatigue and chronic central sensitization. We have many inroads for making a difference.

- Understand collaborative care and combination therapies: The university pain doc reminds me that not only can central sensitization be associated with the generalized pain of fibromyalgia, it can also be part of the tenderness to touch in patients with OA knee pain. Combination strategies for treating pain may help delay arthroscopic and joint replacement surgeries.

- Can make early diagnosis programs available: Population management will offer rheumatologists opportunities to diagnose inflammatory illnesses sooner, using low-cost screening and ultrasound diagnostic tools. These have been developed and studied.

- Have ultrasound & technology savvy: Ultrasound could become the rheumatologist’s stethoscope, used in every patient. It can help identify and direct treatment to inflammatory contributors to carpel tunnel syndrome (peri-tendinitis), shoulder pain (intra-articular vs. bursitis), heel and elbow pain (enthesitis), metatarsalgia (synovitis) and knee pain (Baker’s cyst/effusion). Hip MRIs and fluoroscopy exposure, missed work and treatment delays are frequently avoided when ultrasound diagnosis and guided injections are performed during the scheduled office visit. Ultrasound will facilitate earlier diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis and spondylitis, leading to improved outcomes.21

- Provide patient-centered research and care: Self-management program development and research have been in the purview of rheumatology since Kate Lorig, DrPH, developed and tested the Arthritis Self-Management Program (ASMP) more than 30 years ago. The ASMP has been translated into other languages and promoted by the CDC.22 Population management will incentivize rheumatologists to use this tool, which we too frequently have left on the sideline. If we consider Ed Wagner’s description of an activated patient, I think he raises the bar for all of us. An activated patient a) has insight into the condition and can cope with it; b) makes lifestyle adjustments; c) is committed to following the therapy and/or pharmacotherapy; d) is capable of detecting and interpreting signals from their own body; e) is capable of adjusting medications according to fluctuations during the course of the illness; and f) has meaningful activities during the day.23 An activated patient may not only manage better, but may also calm their overly activated immune system.

Ultimately, it’s all about the patient. Yes, this seems obvious, but watch out for when we start thinking too hard.24 I recently listened to a physiatrist present a one-hour, 30-slide PowerPoint discussion on musculoskeletal integration and care management for a large hospital system ACO—not once was the word “patient” stated or written. The diversity of providers seeing musculoskeletal conditions makes vertical integration and guideline development more complex than for oncology and cardiovascular illness. This elevates the importance of physicians who understand the most complex pathophysiology and current medical therapies, mechanics and rehabilitation principles, and most of all—who listen closely to the patient’s story, values, desires, self-care activities and emotional needs.

Within a Medicare HMO population, enhancing conservative care by listening to and treating the whole patient by trained specialists in rheumatology and sports medicine has been shown to reduce costs significantly.25

What patients say & believe are of equal importance to patient-centered care as their genetic make-up is to personalized care. Care cannot be recommended based on a population average.

Possible New Service Line Strategies & Offerings

Many discussions on listservs and at meetings are necessarily focused on fighting today’s battles while tossing out new ideas. A recent book I received from the RAND Corp., Redefining Healthcare Systems, by Robert H. Brook, MD, concludes with an essay, “Why Not Big Ideas and Big Interventions.” He asks 10 what-if questions, and I share four. What if:

- All communities had a health plan that promoted an environment in which all people could thrive and provided a totally integrated set of social and health services to aid people in need?

- Educational and health policies were replaced with people policies that targeted the interaction between health and education as the way to improve a community’s health?

- Many face-to-face physician visits were replaced by video encounters, encounters with computers and people in the community, or self-directed care—approaches that would be as effective as the traditional patient-clinician interaction but would lower costs?

- Medical expertise was shared so that by means of broadband Internet all people had immediate access, when needed, to world experts—without boarding a plane?

What if your rheumatology office offered a variety of new services with the intention of creating a new dialogue with insurers, employers and patients?

What if you designed and offered a two-month musculoskeletal consultation and care (MCC) package for patients being considered for surgery or expensive spine procedures? If it included initial consultations and up to two follow-up visits by you, a psychologist and a physical therapist, how much would you have to charge at a fixed rate to make this viable? Of course, you would need to include the face-to-face assessment, record review, care coordination and integration of other evaluations, phone and e-mail, and final report preparation time. As with research studies, an administrative overhead and program evaluation time would be built into the case fee, or for a fixed fee as a part of the annual contractual addendum. This is not an independent exam forced by the insurance company, but rather a new benefit they offer. Employers or insurers might incentivize patients to use this new care pathway by offering no co-pays.

Dr. Overman

What if you offered musculoskeletal complex care and case management (MCCCM) for high-expense patients? The setup for this might be similar to an MCC plan, with insurers incentivizing patients to see you for a committed period of time—minimum six months. I would see this as a two- or three-visit fee-for-service assessment and care plan development, with a required sign-off commitment by the patient so the insurer will waive co-pays and/or deductibles for these office services. MCCCM would require patient activation and support care services, care coordination, accessible communication and visits, as well as performance measurements toward agreed-upon goals.

What if your office or network of rheumatologists became an NCQA-accredited patient-centered rheumatology practice? Would your ACO, hospital, local employers or health plans help fund the development through grants or grantees on increased fee-for-service reimbursement plus rewards for transparent reporting? This network strategy may be similar to or an add-on to the pilot program started by the Washington Rheumatology Alliance. The key seems to be the development of collaborative relationships and identification of win-win opportunities.

We are a patient-centered specialty. We take care of complex patients with multiple symptoms & multiple-organ involvement that dramatically affect their lives. Few algorithms exist for integrating all the factors we use to make care decisions.

Finally, what if you organized a group of musculoskeletal providers around your PCSP or PCMH, which offers population data analysis, tracking, care pathways and coordination, accessible early diagnosis, and comprehensive conservative care with a personalized care program for each patient? The care plan would integrate all providers’ recommendations into one plan, set performance milestones and be tailored to the patient’s phase of illness and prioritized on the basis of value (effectiveness/cost). The care activities would be billed on a fee-for-service basis. Rewards would be negotiated annually and be based on performance objectives and cost-sharing of per capita expenditures.

Conclusion

Dr. Overman and TeamOverman, who completed the People’s Coast Classic in September, raised $47,000 for the Arthritis Foundation.

We start our careers in pursuit of the patient story and end the same way. In between, we try to make sense of stories we hear and create a system that allows us to be the most effective, compassionate physician we can be.26

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has stated that over 50% of our healthcare costs are for problems related to patient behaviors. How many patients do you see each day for whom you wished you and your team could offer more education, teach more skills, listen longer, comfort better or better support their pursuit of wellness? I have been blessed to work with a patient to better understand this journey.27 Whether a patient can be their own best-quality advocate (e.g., Alice) or doesn’t have the skills, confidence or emotional resources, each of our patients deserves the possibility of having an illness coach or advocate. I think this alone would move us significantly toward achieving the Triple Aim, but we would need to add system support based on education system principles.

Richard DeLorenzo, a disabilities teacher who was the superintendent of the first school system to ever be awarded the Baldridge Award, transformed his school system from being time based and teacher focused to performance based and student focused.28 Delivering on the Promise: The Education Revolution tells this story, and if you read it, you may see it parallels with our healthcare system crisis. Student focused meant every student had their personalized learning plan that helped them attain the performance goals necessary to advance. Students with similar performance goals worked together, regardless of age, supported by a teacher who focused on where each student was, not where they had been in previous years’ lesson plans/book chapters. In other words, students would advance based on successful attainment, not grade by grade, which only averages success between good performance in one area with barely passing in another. As the student advances grade to grade, the deficiencies never get corrected. In Mr. DeLorenzo’s model, teachers become responsible to each student in helping them succeed in each part of their individualized plan.

If we created a truly patient-centered, performance-based office, what would it look like? What would happen if you became really committed to change?

In the chapter, “Commitment and Moral Purpose,” Mr. DeLorenzo encourages the shift from taking small steps to engaging decisive action by quoting from a passage from The Scottish Himalayan Expedition by William H. Murray:

Until one is committed there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffectiveness. Concerning all acts of initiative (and creation), there is one elementary truth, the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one’s favour all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance, which no man could have dreamt would have come his way.

Through consulting and helping many systems change, Mr. DeLorenzo has concluded and states that transformation can’t occur unless the students/families, teachers and administrators are all committed from the beginning. This may be an important lesson for us—only when patients, providers and payers come together at the population level will we be able to change.

Now, back to my hammock!

Steven S. Overman, MD, MPH, FACR, is associate medical director of QualisHealth, founding member (retired) of The Seattle Arthritis Clinic and professor of clinical medicine at the University of Washington.

Steven S. Overman, MD, MPH, FACR, is associate medical director of QualisHealth, founding member (retired) of The Seattle Arthritis Clinic and professor of clinical medicine at the University of Washington.

Possible Future Rheumatology Care Model

- Care contacts that move away from physician office schedules to on-demand care at their place of work or via the Internet;

- Care management that tracks patient performance and facilitates movement along a comprehensive, personalized care plan;

- Individualized programs that support your patients’ emotional, physical, social and spiritual concerns and conditions;

- Care extenders that reach out to individuals at risk of musculoskeletal morbidity; and

- New care strategies that reduce costs.

References

- Sacre S, Medghalchi M, Gregory B, et al. Fluoxetine and citalopram exhibit potent antiinflammatory activity in human and murine models of rheumatoid arthritis and inhibit toll-like receptors. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Mar; 62(3):683–693.

- 2015 People’s Coast Arthritis Bike Classic presented by Amgen. An Arthritis Foundation Special Event.

- Washington Rheumatology Alliance. The Rheumatology Medical Home Demonstration Project.

- Villeneuve E, Nam JL, Bell MJ, et al. A systematic literature review of strategies promoting early referral and reducing delays in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jan;72(1):13–22. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201063.

- Byyny RL. The tragedy of the electronic health record. Pharos Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Med Soc. 2015 Summer;78(3):2–5.

- RISE: Rheumatology informatics system for effectiveness. American College of Rheumatology. 2015.

- Top questions about ACOs & accountable care. Accountable Care Facts. 2011.

- The IHI Triple Aim. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 2015.

- Taking health management to a new level. Mercer. 2014 Jan 27.

- Patient-centered medical home recognition. National Committee for Quality Assurance. Accessed 2015 Sep.

- Patient-centered specialty practice recognition. National Committee for Quality Assurance. Accessed 2015 Sep.

- The Chronic Care Model. Improving Chronic Illness Care. Published 2006. Updated 2015.

- Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Jan;58(1):26-35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176.

- Workplace health promotion. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013 Oct 23.

- Medical treatment guidelines. Washington State Dept. of Labor & Industries.

- Martin BI, Deyo RA, Mirza SK, et al. Expenditures and health status among adults with back and neck problems. JAMA. 2008;299(6):656–664.

- Hing E, Cherry DK, Woodwell DA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2004 Summary. DHHS Publication No. 2006-1250, No. 374. 2006 Jun 23.

- Pharmaceutical company programs that help lower the cost of medication. Arthritis Foundation. 2015 Jan 27.

- Goodlier R. Rising costs of biologics in the U.S. suggest need for negotiation ability. 2015 May 21. The Rheumatologist website. .

- Pollack A. Cost of treatment may influence doctors. The New York Times. 2014 Apr 17.

- Aslanyan E. Challenges to early diagnosis in spondyloarthritis: A look at two recent studies. Spondylitis Association of America. 2015 Aug 6.

- Self-management education: Arthritis self-management (ASMP). Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. 2012 Dec 17.

- Workshop summary: The activated patient. 14th Dutch Congress of Physiotherapists.

- Hoff B. (1983). The Tao of Pooh. New York: Penguin Books.

- verman SS, Kent DL, Uslan DW, Lewis RS. Cost of care and patient-satisfaction from routine referral to nonsurgical musculoskeletal specialists in a medicare risk plan. J Clin Rheumatol. 1998 Jun;4(3):120–128.

- Overman SS. Compassionate care: A more affordable approach to patient care. King County Medical Bulletin. 2013 Apr.

- Selak J, Overman SS. (2012) You Don’t Look Sick: Living Well with Chronic Invisible Illness (2nd Ed). New York: DemosHealth.

- From Baldrige Performance Excellence Program. 2015. 2015–2016 Baldrige Excellence Framework: A Systems Approach to Improving Your Organization’s Performance. Gaithersburg, MD: U.S. Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology.