It’s not often that rheumatologists name and define a recognized disease entity, but lack a framework to diagnose the disease.

In the recent past, it was conceptually understood that ankylosing spondylitis (AS) patients do not develop radiographic sacroiliitis soon after developing the symptoms of the disease, but we had limited ways to objectively assess such patients. In addition, there was no accepted nomenclature to label their condition. The past few years have witnessed remarkable progress in our understanding of the natural history, epidemiology and genetics of our patients who have axial skeletal inflammation—some of whom may develop structural damage at the sacroiliac joints at a later stage. This process has led to defining axial spondyloarthritis as an umbrella term, which includes AS plus patients with axial inflammation who do not have X-ray changes suggestive of structural damage that currently defines AS.1

This article touches upon the recent developments in this field, tries to clarify some misconceptions regarding the use of the new terminology and discusses new questions raised regarding the appropriate application of the axSpA classification criteria.

Spectrum of Disease

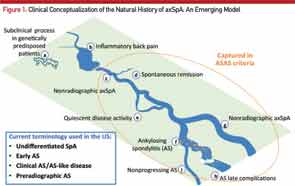

Axial spondyloarthritis is not just the “early stage of AS”: It is the entire spectrum of disease, which includes AS plus those with axial inflammation who may or may not develop the structural damage that defines AS at a later stage.

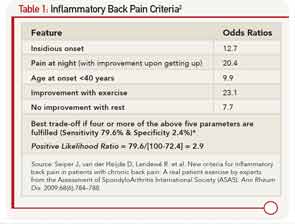

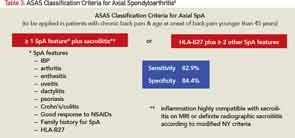

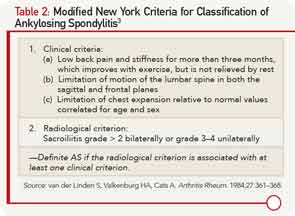

The most common presenting symptom of immune-mediated inflammatory involvement of the axial skeleton is chronic low back pain, most likely inflammatory back pain (see Table 1).2 Clinical features, such as asymmetric oligoarthritis, psoriasis, uveitis or enthesitis, may be present at this early stage, suggesting the presence of spondyloarthritis. Radiographic sacroiliitis would be absent at the early stage, and thus, such a person cannot be classified as AS using the modified New York (mNY) Criteria (see Table 2).3 Observational studies have shown that about 12% of such patients would progress to develop AS over two years and about 70% over the long term.4 High CRP, extensive MRI changes of sacroiliitis, male sex and smoking are risk factors for such a progression.5 The Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) has proposed a new term, axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA), to describe the entire spectrum of this disease in which the condition of patients who fulfill the modified New York (mNY) criteria is called ankylosing spondylitis, and that of patients not fulfilling the X-ray criteria is called nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA)6 (see Table 3, Figure 1).

The ASAS classification criteria require the patient have chronic low back pain (i.e., longer than three months’ duration) starting before the age of 45 years and either the presence of sacroiliitis on imaging (i.e., X-ray or MRI scan) with one typical feature of spondyloarthritis or the presence of HLA-B27 and two features of spondyloarthritis6 (see Table 3).

The obvious advantage of these criteria is to help recognize the nonradiographic forms of the disease so the rheumatologist can initiate early treatment. Although the sensitivity and specificity of these criteria are quoted to be 83% and 84% respectively, inappropriate application of the classification criteria for diagnostic purposes—especially in the absence of any objective signs of inflammation—in clinical practice may lead to errors. It’s imperative to understand that although the same clinical features included in the classification criteria are used in making the diagnosis, in practice, one first needs to rule out other common conditions that may cause similar symptoms. In addition, one needs to take into consideration the pretest probability of axSpA. Checking boxes of the classification criteria set would indeed lead to inaccurate conclusions.

With tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors (TNFi) showing promise in large trials on nr-axSpA patients, such erroneous diagnosis may lead to inappropriate treatment with expensive and potentially harmful medication. The question of how to avoid this over-diagnosis and inappropriate treatment was central during the discussions held at a recent Federal Drug Administration (FDA) advisory committee meeting and led to the denial of approval for both adalimumab and certolizumab for the treatment of nr-axSpA patients. This FDA denial means that there is no approved medication to treat nr-axSpA in the U.S. and has led to new questions:

What should the regulatory pathway be for approval of new agents for nr-axSpA? How can we prevent the unintended use of the classification criteria for diagnostic purposes? Do we need new diagnostic criteria for axial spondyloarthritis? Has the time come to update the Modified New York Criteria that were developed 30 years ago in the pre-MRI era?

MRI’s Role

What is the appropriate role of MRI of the sacroiliac joints and HLA-B27 in daily practice for establishing the diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis? In the era of prudent use of healthcare dollars, it’s important to order expensive investigations only as a part of a thoughtful protocol for diagnostic evaluation. A patient with chronic low back pain (i.e., lasting for three months or longer) starting before the age of 45 has a 5% chance of having axSpA.7 Before ordering expensive investigations, a careful history (including past history and family history) and detailed physical examination may reveal signs and symptoms of spondyloarthritis and would increase these odds dramatically. The presence of inflammatory back pain on history would increase the odds of axial spondyloarthritis to 14%, and an additional one or two SpA features would increase the odds to 35–70%, respectively.7 In this situation, the presence of HLA-B27 or X-ray changes of sacroiliitis should clinch the diagnosis of axSpA or AS respectively.

Here, the course of axial SpA is compared to the course of a river. A) Some people may be genetically predisposed to develop axial SpA but may never develop any clinical manifestations of the condition or may have a subclinical disease. B) According to the recent NHANES study (2009–2010), inflammatory back pain is found in 6% of U.S. population, but only a small percentage of those will develop C) nonradiographic axial SpA (nr-axSpA). D) A small percentage of these people may have a spontaneous remission, and E) some may have a quiescent disease course. F) Studies have shown that up to 12% of nr-axSpA patients develop ankylosing spondyloarthritis (radiographic sacroiliitis) in two years; whereas, others may continue as G) nr-axSpA. Not all ankylosing spondylitis patients have a progressive course, either. Some progress to develop long-term complications H), and others may have a relatively benign but chronic course I). Adapted from van Vollenhoven RF. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011 Apr;7(4):205–215.

MRI of the sacroiliac (SI) joints has emerged as the imaging investigation of choice for patients with suspected axSpA who do not have X-ray evidence of sacroiliitis. On T2-weighted fat-suppressed sequences (called STIR sequences) of the MRI, active inflammatory lesions of osteitis are seen as bone marrow edema (BME). MRI can also detect other lesions, such as synovitis, enthesitis and capsulitis, associated with SpA. Among these, the clear presence of a single osteitis lesion on two consecutive slices or two osteitis lesions on a single MRI slice is considered essential for defining active sacroiliitis.8 Structural damage lesions, such as sclerosis, erosions, fat deposition and ankylosis can also be detected by MRI on T1-weighted images.9

Although an MRI scan of the SI joints is progressively used in the early diagnosis of nr-axSpA, it has several limitations. The BME seen on STIR images used to diagnose sacroiliitis can also be seen in normal adults, young patients with trauma and older patients with degenerative arthritis of the SI joints. Also, because AS patients have intermittent sacroiliac joint inflammation, the absence of BME cannot rule out axSpA. Signs of structural damage on T1-weighted images of the SI joints described above could increase the specificity of the diagnosis,9 although the exact location for structural damage lesions for diagnosis and classification is less clear.

Finally, as with every other diagnosis in rheumatology, expensive investigations can only supplement and not replace the thoughtfulness that goes into making an accurate clinical diagnosis. Ordering HLA-B27 or an MRI scan of the SI joints in patients who have no other features of SpA or whose back pain started after the age of 45 should be avoided.

Prevalence

Axial spondyloarthritis may be as prevalent as rheumatoid arthritis, and nr-axSpA has disease burden comparable to AS.

The 2009–10 National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES) screened 6,684 persons (ages 20–69), and 5,106 were interviewed using a tool specifically designed to survey U.S. adults for the presence of spondyloarthritis.10 It was found that nearly 20% of the U.S. population has chronic low back pain at any given time, and the prevalence of inflammatory low back pain (IBP) was close to 6%. The overall age-adjusted prevalence of axSpA was 0.9% to 1.4% using the Amor and European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group criteria.10 The ASAS classification criteria were not used in the NHANES study because the criteria were not ready when the NHANES study rolled out.

When compared with the recent estimates of the prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) being 0.6 to 1%, these new NHANES data suggest that axSpA may be at least as prevalent as RA in the U.S. population. However, these numbers are not reflected in a typical U.S. rheumatologist’s office, and most rheumatologists do not see as many axSpA patients as RA patients in their practice. This observation may be a reflection of the referral patterns. In contrast to the RA patients, axSpA patients are probably not referred to rheumatologists and are seen by their primary care providers or chiropractors, or could be evaluated by the orthopedic surgeons and neurosurgeons in spine centers for back pain. Clearly, there is an unmet need for early identification and assessment of these patients because appropriate medical treatment can substantially improve quality of life and avoid unnecessary surgical interventions.

Several studies have shown that the disease burden in nr-axSpA patients, measured by such validated instruments as SF-36 questionnaire or Bath AS disease activity index, is comparable to that of AS.11 This observation combined with the prevalence of axSpA in the U.S. population depicts the true burden of this disease on society.

Genetic Markers

Identification of new genetic markers can inform us about the pathophysiology of axSpA.

More than 90% of Caucasian AS patients are known to be positive for HLA-B27, a major disease-susceptibility gene that contributes 40% of the population-attributable risk for AS in Caucasians. Because it’s a major histocompatibility (MHC) class I molecule involved in antigen presentation, it was originally thought to be presenting an arthritogenic peptide. Failure of finding such a peptide led to alternate theories of how the HLA-B27 molecule could be important in the AS pathogenesis. It’s known the molecule tends to misfold (causing an inflammatory unfolded protein response or UPR) and can form covalent heavy chain homodimers on the cell surface that could be recognized by natural killer cells. More recently, it has been proposed that the HLA-B27 can modulate the human microbiome to create a proinflammatory milieu and development of the disease.12

Modern technological advances have led to the identification of several novel non-MHC genes that may hold clues to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of AS. Two of the most promising new genes are the ERAP1 gene encoding aminopeptidase 1, an enzyme present in the endoplasmic reticulum involved in cutting peptides for loading onto class I MHC molecules, and the interleukin 23 receptor (IL-23R) gene that encodes for the IL23R expressed on the TH17 cells.13 The ERAP1 association is seen primarily in HLA B-27–positive patients, bringing back the arthritogenic peptide theory; whereas, the UPR and homodimer formation described above has been shown to increase IL-23 production, implicating TH 17-positive cells in the pathogenesis. In a mouse model, a novel CD3 and ROR γT positive, but CD4 and CD8 negative T cell population bearing the IL-23 receptor was recently described.14 The IL-17 and IL-22 secreted by these cells could explain the inflammatory and the osteoproliferative manifestations of spondyloarthritis, respectively.14 The importance of the IL-17 pathway in the pathogenesis of spondyloarthritis has led to investigations of IL-17 inhibitors in the treatment of AS.

Limited Treatment Options

Compared with RA, axSpA patients have limited treatment options, although the choices are increasing.

Most treatment studies in axSpA have been conducted in AS population and not in nr-axSpA patients. Unlike RA, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have a major role to play in the treatment of axSpA; whereas, the disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have a very limited role.15 A majority of axSpA patients show a very good (50% improvement or better) response to NSAIDs. The only DMARD to show limited efficacy in the treatment of axSpA has been sulfasalazine, which may be useful only in treating peripheral arthritis.15 Methotrexate and leflunomide have shown no efficacy on either axial or peripheral joint disease, but it is not uncommon to find these DMARDs being used to treat AS patients.

After physical therapy and NSAIDs have failed to give sufficient relief to patients, TNFi are used.15 Five TNFi (i.e., etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab and certolizumab) have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of AS, and they all show remarkable similarity in their efficacy in relieving the important symptoms of axSpA. Studies have shown that TNFi improve health-related quality of life, patient-reported outcomes, anemia, sleep quality, fatigue, bone density and even forced vital capacity in patients with AS.16-20 Elevated levels of C-reactive protein and evidence of osteitis on SI joint MRI scan are predictors of a good response to TNFi therapy. However, as mentioned previously, no TNFi has been approved to treat either nr-axSpA or the entire spectrum of axSpA.

Unlike RA, in which the structural damage refers to the catabolic changes of loss of cartilage and bony erosions, axSpA leads to catabolic plus anabolic changes in the form of syndesmophytes and ankylosis of the joints. The initial studies of two years of treatment with TNFi failed to show a reduction in new bone formation, although these studies were criticized for using a historical control group and for being of inadequate duration. It did start a debate on whether the new bone formation is uncoupled from the underlying inflammatory process. Careful analysis of prospective data on spinal MRI shows that, in some patients, the early inflammatory changes of osteitis can progress to fatty infiltration, which can be the precursor of new bone formation. Research has identified several important mediators in this process, such as bone morphogenic proteins, molecules in the SMAD and WNT signaling pathways, that could be targeted for future therapies to prevent osteoproliferation.21 Adequate doses of NSAIDs (blocking prostaglandin E2, a molecule that acts synergistically with WNT) and more recently long-term (i.e., longer than four years) treatment with TNFi (eliminating osteitis before fatty changes) have been shown to reduce the rate of new bone formation in patients with AS, but not in nr-axSpA.22,23

Trials of abatacept, rituximab and tocilizumab, all approved for the treatment of RA, have yielded insignificant results with regard to efficacy in AS patients.24-26 It’s encouraging to note that the IL-17 pathway is now being targeted for manipulation. Secukinumab a monoclonal antibody against IL-17A and ustekinumab blocking the P40 subunit of IL-12/IL-23 have shown efficacy in proof-of-principle studies for the treatment of AS.27-28 Apremilast, a small molecule inhibiting phosphodiesterase E4 (unrelated to the IL-17 pathway), is also being studied in phase 3 trials in AS.

The ACR, the Spondylitis Association of America and Spondyloarthritis Research & Treatment Network are developing treatment recommendations for axSpA, and these are expected to be completed by the end of 2014.

Tasks Ahead

Although significant progress continues to be made in defining the spectrum of axial spondyloarthritis, its epidemiology, genetics and management, several questions remain unanswered.

MRI scan of the SI joints has been vital in early diagnosis, but its role in monitoring disease progression or response to treatment is uncertain.

Whether a combination therapy of NSAIDs with TNFi or new biologics is better in achieving remission and preventing osteoproliferation remains to be seen.

Personalized treatment can be possible only by improved understanding of genetics and baseline characteristics predicting response.

Lastly, although the ASAS classification criteria have helped identify patients with axial inflammatory arthritis who do not fulfill the 30-year-old Modified New York Criteria for Ankylosing Spondylitis, the discussions at the FDA advisory committee and the subsequent FDA decision has raised serious questions about their use in clinical practice. Have these criteria inadvertently hurt the cause of early treatment? Now, the biggest unmet need in this field is how we are going to manage the so-called nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis patients. One of the tasks ahead would be to consider redefining ankylosing spondylitis by not just the sacroiliitis on radiographs, but also by using modern imaging techniques.

Atul Deodhar, MD, is professor of medicine in the Division of Arthritis & Rheumatic Diseases (OP09) at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

References

- Rudwaleit M, Landewé R, van der Heijde D, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part I): Classification of paper patients by expert opinion including uncertainty appraisal. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:770–776.

- Seiper J, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. New criteria for inflammatory back pain in patients with chronic back pain: A real patient exercise by experts from the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):784–788.

- van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:361–368.

- Poddubnyy D, Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, et al. Rates and predictors of radiographic sacroiliitis progression over 2 years in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(8):1369–1374.

- Poddubnyy D, Haibel H, Listing J, et al. Cigarette smoking has a dose-dependent impact on progression of structural damage in the spine in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: Results from the GErman SPondyloarthritis Inception Cohort (GESPIC). Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(8):1430–1432.

- Rudwaleit M, Landewé R, van der Heijde D, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): Validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:777–783.

- Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Khan MA, et al. How to diagnose axial spondyloarthritis early. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:535–543.

- Rudwaleit M, Jurik AG, Hermann KG, et al. Defining active sacroiliitis on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for classification of axial spondyloarthritis: A consensual approach by the ASAS/OMERACT MRI group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(10):1520–1527.

- Weber U, Lambert RG, Pedersen SJ, et al. Assessment of structural lesions in sacroiliac joints enhances diagnostic utility of magnetic resonance imaging in early spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(12):1763–1771.

- Reveille JD, Witter JP, Weisman MH. Prevalence of axial spondyloarthritis in the United States: Estimates from a cross-sectional survey. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(6):905–910.

- Kiltz U, Baraliakos X Karakostas P, et al. Do patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis differ from patients with ankylosing spondylitis? Arthritis Care Res. 2012 Sep;64(9):1415–1422.

- Rosenbaum JT, Davey M. Time for a gut check: Evidence for the hypothesis that HLA-B27 predisposes to ankylosing spondylitis by altering the microbiome. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3195–3198.

- Haroon N, Inman RD. Endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidases: Biology and pathogenic potential. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010 Aug;6(8):461–467.

- Sherlock JP, Joyce-Shaikh B, Turner SP, et al. IL-23 induces spondyloarthropathy by acting on ROR-γt+ CD3+CD4-CD8- entheseal resident T cells. Nat Med. 2012;18(7):1069–1076.

- Braun J, van den Berg R, Baraliakos X, et al. 2010 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):896–904.

- Davis JC Jr, Revicki D, van der Heijde DM, et al. Health-related quality of life outcomes in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis treated with adalimumab: Results from a randomized controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1050–1057.

- Furst DE, Kay J, Wasko MC, et al. The effect of golimumab on haemoglobin levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology. 2013;52:1845–1855.

- Deodhar A, Braun J, Inman RD, et al. Golimumab reduces sleep disturbance in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: Results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:1266–1271.

- Visvanathan S, van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, et al. Effects of infliximab on markers of inflammation and bone turnover and associations with bone mineral density in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(2):175–182.

- Dougados M, Braun J, Szanto S, et al. Efficacy of etanercept on rheumatic signs and pulmonary function tests in advanced ankylosing spondylitis: Results of a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study (SPINE). Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(5):799–804.

- Lories RJ, Schett G. Pathophysiology of new bone formation and ankylosis in spondyloarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2012;38(3):555–567.

- Poddubnyy D, Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, et al. Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on radiographic spinal progression in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: Results from the German Spondyloarthritis Inception Cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1616–1622.

- Haroon N Inman RD Learch TJ, et al. The impact of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors on radiographic progression in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2645–2654.

- Song IH, Heldmann F, Rudwaleit M, et al. Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with abatacept: an open-label, 24-week pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Jun;70(6):1108–1110.

- Song IH, Heldmann F, Rudwaleit M, et al. Different response to rituximab in tumor necrosis factor blocker-naive patients with active ankylosing spondylitis and in patients in whom tumor necrosis factor blockers have failed: A twenty-four-week clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1290–1297.

- Kiltz U, Heldmann F, Baraliakos X, et al. Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis in patients refractory to TNF-inhibition: Are there alternatives? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:252–260.

- Baeten D, Baraliakos X, Braun J, et al. Anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody secukinumab in treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013 Sep 12. pii: S0140–6736(13)61134-4.

- Poddubnyy D, et al. ACR 2013 annual meeting, Abstract #1798.