What some people won’t do for love.

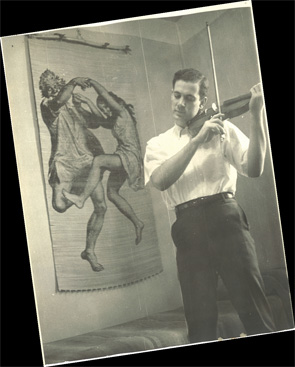

Allen Steere, MD, had his first crush on a girl at age 12. Her name was Gretchen. She was a bit different than most young girls at his school: She played the violin.

At the time, Dr. Steere, now professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a rheumatologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston, played the piano. But he liked Gretchen more than he liked playing the piano, so he took up the violin in hopes of spending more time with her and impressing her with his musical ability.

Over the years, it was Dr. Steere’s love of the violin that flourished. He studied and performed with some of the world’s greatest musicians and teachers. At age 28, however, he was forced to give up his life’s passion due to focal dystonia, a disorder involving involuntary contractions. With no cure or treatment available, he learned to compensate for his disability and returned to his musical roots—the piano. After hundreds of performances, he says he needs to make music just as much as he needs to heal patients, and he feels grateful for the opportunity to do both. [Audio clip: Listen to Dr. Steere’s thoughts on what music contributes to his life, his practice and to medicine.]

Practice Pays Off

Dr. Steere says he chose the violin because it’s a very important instrument in an orchestra, partially because it’s really the only one that mimics the human voice. “It’s a very expressive instrument, as the human voice is an expressive instrument,” he explains.

After countless hours of private violin lessons and daily practice, Dr. Steere was a fairly accomplished violinist by age 18. He began performing with the orchestra in his hometown in Indiana—The Fort Wayne Philharmonic Orchestra.

While attending Columbia College and then Columbia Medical School during the 1960s, Dr. Steere became the concertmaster of the college’s orchestra, performing a concerto each year. Even in medical school, he made time to piece together an orchestra that was largely composed of other medical students. Every year, he also played a concerto with the orchestra, and every month, he gave solo performances at recitals throughout the city.

Dr. Steere possessed both the talent and good fortune to study privately with Ivan Galamian for eight years. Galamian taught violin at The Julliard School and is recorded by history as the greatest violin teacher of the 20th century. Galamian founded a summer program called Meadowmount School of Music in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York, which Dr. Steere and other exceptional music students attended.

It was there—at Meadowmount—where Dr. Steere played with David Garvey, the pianist for Mary Violet Leontyne Price, a famous American soprano. He also performed in the same string quartet as then 15-year-old violin virtuoso Itzhak Perlman.

“Itzhak Perlman was unique,” says Dr. Steere, who attended the Meadowmont school for five summers. “He had a fabulous technique, and there was a beauty in his playing. Already by age 15, he could play anything written for the violin.”

Misfortune & Opportunity

Dr. Steere continued with both his passions—music and medicine—until he reached age 28. He was in his medical residency when he began experiencing trouble with the fourth finger on his left hand. It began moving on its own, beyond his control, which is devastating for any violin player.

“At the time I developed [focal dystonia], no one understood what it was,” he says, adding that it developed slowly over time. “Much more is known about it now. It happens to about one in 200 musicians. Still, there’s very little that can be done about it. It’s often career ending.”

Unfortunately, that was the case with Dr. Steere, who hasn’t been able to play the violin since then. However, he had no intention of surrendering his musical career. Instead, he returned to playing the piano, simply picking up where he left off when he was almost a teenager.

“With the piano, you can play with your fingers flatter than with the violin, where they have to be curved,” he says, adding that Leon Fleisher, a famous American pianist and conductor, also developed the same condition. “It’s having them curved that becomes a problem.”

It didn’t take long before he began performing classical music by all the great composers, such as Bach, Beethoven and Mozart. He has performed at two meetings sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology and for students attending a summer music program in Chautauqua, N.Y., where Dr. Steere owns a vacation home. He says Marlena Malas, the chair of the voice department at the Chautauqua Institute and faculty member of the Julliard and Manhattan schools of music, invites her students to the summer program.

Now at age 71, Dr. Steere still performs. In August 2013, during the sing-out at the close of the Chautauqua summer music school season, he was the pianist for singer Julian Arsenault, a baritone, who now performs with the Dresden Opera Company in Germany. (Note: A video of the performance is available.)

Dr. Steere is also the pianist for his church choir.

“I’m a member of the Wellesley Congregational Church choir, so that’s a regular and active way of expressing music in my life now,” he says.

Some people may feel cheated after a disorder partially robs them of a promising musical career. But when Dr. Steere looks back, there’s no bitterness or anger, just fond memories and extreme gratitude.

Whether playing the violin or the piano, he says music has always offered balance in his life, enhanced his listening skills as a physician and served as the backdrop for many of his long-term friendships.

He still remains good friends with Perlman and other famous violinists he grew up with, such as Pinchas Zuckerman, following their careers with great interest. Roughly 60 years later, he also keeps in touch with Gretchen, perhaps the person most responsible for his musical journey.

“It has worked out for the best,” says Dr. Steere. “It wasn’t the way I envisioned [my life] when I was younger, … but on the other hand, I feel I’ve been able to lead a very rewarding life in medicine.”

Carol Patton, a freelance writer based in Las Vegas, Nev., writes the Rheum after 5 column for The Rheumatologist.