In addition to seeing patients and managing their conditions, Edward Fudman, MD, a rheumatologist in Austin, Texas, has recently been doing a great deal of something else—rewriting a prescription he’s already written because of a drug shortage.

Patients more and more frequently have been going to the pharmacy only to be told that the prescribed drug is unavailable. When Dr. Fudman finds out that the brand-name drug is available, he often has to write another prescription.

“It’s just one more hassle in the day in a long list of hassles that don’t really have to do with taking care of patients,” Dr. Fudman says.

An Increasing Problem

The rate of drug shortages has been rising steadily in recent years, due to quality questions at manufacturers, consolidation in the drug-manufacturing industry, and other factors, according to data from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other sources.

Much of the attention to the problem has centered on the shortage in cancer drugs, but rheumatology has seen its share of shortages, too, forcing patients to struggle in their search for medications, and sometimes adding to their pain and discomfort.

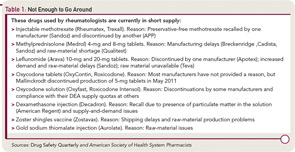

Drugs frequently prescribed by rheumatologists that were in short supply as of September 2011 include leflunomide tablets, injectable methotrexate, and metylprednisolone tablets. And there are many others in short supply now or that have been in short supply recently.

Kathryn Dao, MD, a rheumatologist at the Baylor Research Institute in Dallas and co-editor of the ACR’s Drug Safety Quarterly (DSQ), says it’s a worsening problem in rheumatology.

“We have been encountering more drug shortages lately,” she says. “Currently, it has been more of an annoyance than a problem, but I foresee this becoming a larger issue. We have been able to work around the shortages by finding appropriate substitutes that have similar efficacy, similar side effect profiles, and similar costs; however, I wonder how much longer we would be able to do this.”

John J. Cush, MD, co-editor of DSQ and director of clinical rheumatology at the Baylor Research Institute, says the shortages have been a source of headache for patient and physician.

“You have to find new ways to write for the drug, like different doses or use the original trade name to get the prescription filled,” he says. “It’s a major inconvenience for the patients and for the prescribing doctors.”

DSQ frequently lists drugs used in rheumatology that are in short supply.

One Patient’s Struggle to Get Leflunomide—without Breaking the Bank

Roxie Greenway has been on leflunomide for 11 years. It’s been a crucial medication for her rheumatoid arthritis. When she tried the first-line treatment, methotrexate, she developed pneumonia-like “methotrexate lung.”

When she tried to get leflunomide refilled in June, her insurance company told her it was going to cost her $600 for the three-month supply, rather than the usual $30.

The generic, which she normally used, was out of supply, so she would have to get the brand-name drug—and pay for it.

“The brand is exorbitantly expensive, so it’s extremely difficult to get the prescription filled and not have to pay a $600 co-pay,” says Greenway, who lives in Austin, Texas.

Greenway says she has gotten used to haggling with the insurance company to get the co-pay reduced. “It usually takes three layers of approval,” she says. “Usually you have to go through several layers.”

Greenway ended up having to pay $80—still more than the usual $30 but much less than $600—and it took 25 days from the time she first tried to have the prescription refilled. She went without the drug for three or four days, but it takes about two weeks without it to start feeling any ill effects, she says.

Greenway’s physician, Dr. Fudman, says patients should not have to haggle with pharmacies and insurance companies if a generic is not available but the brand is. He says he notes “product selection permitted” on the prescription, but that often doesn’t work.

“When you sign the form ‘product selection permitted’ it should mean just that,” he says. “If it’s written as a generic name and all they have available is the brand then that’s what they should dispense. And insurance companies shouldn’t penalize patients for it as they do when patients want the brand drug instead of a generic version, if in fact there is no generic drug available.”

Kevin Schweers, a spokesman for the National Community Pharmacists Association, says there is no easy solution in a situation like Greenway’s.

“First, if a particular generic isn’t immediately available, a community pharmacist will work with their wholesaler and backup wholesaler(s) to get it in stock,” he said in e-mailed remarks. “If, after exhausting those options, it is still not obtainable, substituting a brand-name for a generic, as you describe, can be difficult. The bottom line is the patient’s insurance almost certainly would reject the claim.”

Dr. Dao says, “some patients have been resourceful.”

Some, like Greenway, have been dogged with insurance coverage, with mixed success. Others have managed to buy their drug from hospital pharmacies and others have warily bought their medication online. If their attempts fail, they check with the doctor about alternatives.

Greenway seems to have been fortunate. She says she now has the name of a helpful supervisor with the insurance company she hopes will allow her to circumvent much of the frustration next time. “It’s not my fault that they’re not making the generic,” she says. “But, unfortunately, it’s my problem.”

Rheumatology Feeling the Lack

Dr. Cush emphasizes that drug shortages in rheumatology, while a serious problem, have not risen to a catastrophic level. He says that none of his patients has suffered permanent harm or damage due to a drug shortage, as has been seen with cancer patients.

“While there are certain patients who’ve been inconvenienced by this, I would not say this has been a show-stopper for rheumatology,” he says. “We have enough alternatives that short supply has not shut down patient care.”

Dr. Fudman says that, for many patients, there is only one optimal drug.

“There’s not such a wide variety of drugs in rheumatology that it’s easy to switch off of various things,” he says. “If somebody’s on methotrexate, they’re on methotrexate. If they’re on leflunomide, they’re on leflunomide. These are drugs that take a long time to build up their efficacy. It’s not something you can switch back and forth.”

The FDA says it confirmed 178 cases of drug shortages in 2010—a record number. That was up from 55 shortages five years ago.1

According to the University of Utah Drug Information Service, there were 120 shortages reported in the U.S. in 2001—but that number has risen to 211 in 2010.

Through September of this year, 200 shortages were reported.2

Senate Bill Would Require Advance Notice of Potential Shortage

If rheumatologists and pharmacists were to get early warning that a drug might soon be in short supply, they may be able to better prepare their patients and help them adapt, perhaps pursuing other medications sooner, if possible.

Advance notice, though, is often more of a wish than a reality.

But a bill (S. 296) proposed in the U.S. Senate by Sens. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) and Bob Casey (D-Pa.) would require that drug manufacturers notify the U.S. Food and Drug Administration of factors that might lead to a drug shortage.

Advocate groups are pushing for a notification at least six months ahead of time.

The law would give the FDA the ability to impose penalties for not reporting such circumstances, although what those penalties would be is not yet determined.

The bill so far has stalled in committee, but its supporters hope legislation to tackle the shortage problem can eventually be passed.

“Often, the first time pharmacists even learn about something not being available is when they order it and they get a notice back from the drug wholesaler or the company that it’s back-ordered,” says Michael Cohen, the president of the nonprofit Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP).

The FDA’s ability to avoid drug shortages is limited because there is no such advance-warning requirement. The FDA also does not have the ability to force a drug manufacturer to make a drug, although it can intervene in cases where a drug considered medically necessary is facing a shortage. In those cases, the FDA can work with manufacturers to boost production, expedite the approval process, or help with finding alternative sources of raw materials.

Without saying outright that the agency supports the legislation, FDA spokeswoman Yolanda Fultz-Morris said, in an e-mail, “Early notification helps us in many cases to avoid shortages and we continue to encourage manufacturers to notify us when they experience any issue which could lead to a change in supply.”

Dr. Dao says notification should be required when a drugmaker ceases manufacturing of a drug, noting that the FDA reports that 38 shortages were prevented last year because companies voluntarily informed the FDA about circumstances that may have led to shortages. “Makes one wonder,” she says, “how many more could have been prevented if there was mandatory reporting.”

“In the past couple of years, it’s just been exponential,” says Diane Ginsburg, the immediate past president of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and clinical professor and assistant dean for student affairs at the University of Texas’ College of Pharmacy in Austin.

According to the FDA, 77% of the shortages in 2010 involved sterile injectable drugs.

“There are fewer and fewer firms making these older sterile injectables, and they are often discontinued for newer, more profitable agents,” FDA spokeswoman Yolanda Fultz-Morris says in an email. “When one firm has a delay or a manufacturing problem, it is extremely difficult for the remaining firms to quickly increase production.”

The biggest cause for the shortages in those drugs has been product quality issues, namely microbial contamination and newly identified impurities, according to the FDA. From January to October of 2010, 42% of drug shortages were due to quality problems.

Eighteen percent were due to product discontinuation by the manufacturer and another 18% were due to delays and capacity problems. Nine percent were due to difficulties getting raw materials and 4% of the sterile injectable shortages were due to increased demand because there was a shortage of another injectable medication—in other words, one shortage led directly to another.

Kevin Schweers, a spokesman for the National Community Pharmacists Association, says generic drugs, especially schedule II substances, have been in short supply. But there can be problems even when one generic is available to replace another generic.

An example, he says, is when a “new generic substituted in place of the old one is made by a different manufacturer and may come in a different color or shape. That can leave patients wondering and asking the pharmacist why their medication is different or if a mistake was made.”

Some healthcare professionals say patient safety has been affected, according to 1,800 healthcare practitioners who participated in a survey last year conducted by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), a nonprofit group. Twenty percent of the respondents said drug shortage–related errors were made, while 32% says they had “near misses” related to drug shortages. Nineteen percent said there had been adverse patient outcomes as a result of drug shortages.

The study noted two instances where patients died when they were switched to dilaudid because morphine was in short supply; both patients were given doses appropriate for morphine instead of doses adjusted for dilaudid.

Dr. Fudman says that the extent of the health effects on his rheumatology patients is pain and swelling if there is a delay in getting their medications. They also may have to take two pills rather than one, if a certain strength is in short supply, or get more frequent injections, as was the case when triamcinolone (Aristospan, Amcort, Aristocort) experienced a shortage.

“Aristospan is by far the best injectable steroid for joint injections, and the longest-lasting response,” he says. “When we don’t have that available, we inject with Kenalog or something else, and they don’t get as long lasting a response,” requiring another injection sooner.

Dr. Dao says one of the most potentially significant problems is with the shortage in the shingles vaccine, often given before a patient is started on biologic therapy to prevent that side effect.

“There are patients who would benefit from the shingles vaccine before they start biologic therapy,” she says. “Due to the unavailability of the vaccine, some have foregone the vaccine and started their biologics. It unclear whether this decision will significantly increase their risk for shingles in the future.”

Lack of Notice a Problem

Physicians in rheumatology and other fields say that they often are not notified about a drug shortage before their patients experience it themselves.

Dr. Fudman and others say that they get their information about shortages, including the cause and the expected date when the drug will again be easily available, from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists website (www.ashp.org/DrugShortages/Current).

He does get e-mails about shortages from the ACR, but almost always after a patient has already told him about the shortage after he or she tried unsuccessfully to get a prescription filled, he says.

But, he says, he isn’t sure how useful advance notice would be anyway, because it probably wouldn’t affect what he prescribes—there’s a chance the drug would still be available on the shelf.

“Even if they told us that ahead of time, I’m not sure what we would do, other than tell patients, ‘If your pharmacy says they don’t have it, try another pharmacy,’ which is what we do anyway,” Dr. Fudman says.

Dr. Cush says that while he thinks the effects of shortages will continue to be felt mostly outside rheumatology, the overall problem isn’t likely to improve soon—because manufacturers have so much discretion in what they produce.

“The problem is it’s a free-wheeling environment when it comes to generics, in what they will make and what they won’t make,” he says. “I think it’s going to get worse before it gets better.”

Thomas Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drug Shortages. Available at www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/drugshortages/default.htm. Accessed September 21, 2011.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Drug Shortages: Current Drugs. Available at www.ashp.org/Drug Shortages/Current. Accessed September 21, 2011.