Knowledge and experience of primary care physicians are not sufficient for optimal chronic disease management. In our view, primary physicians often do not possess the depth of knowledge and experience across the spectrum of complex chronic diseases to provide care at the level provided by specialists. Expecting more from primary care providers in the area of traditional subspecialty care is unrealistic. The increase in specialization across a broad range of chronic diseases has been driven not only by an increase in the number, sophistication, and complexity of procedures, but also by the rapid proliferation of knowledge throughout medicine that has led to multiple options for diagnosis and treatment. Advances are too numerous and occur too rapidly for any one physician or specialty to learn about them and then to stay current. This challenge accounts in part for the widely documented problems with diagnosis, timely referral, and optimal treatment, and the 17-year lag to adoption of new discoveries into standard care.14,16 Moreover, the expectation that computer-based decision support will close these gaps seems unrealistic to us.

As one example of the differences in care depending on provider, rheumatology care for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is more effective than primary care, as shown by Catherine MacLean and co-authors in a large insurance company cohort of 1,355 RA patients.17 A yearly physical exam, sedimentation rate, and drug monitoring were provided to 75% of patients receiving rheumatology care and 47% of those managed by primary physicians.

Another example of provider differences in management relates to the initial evaluation of early arthritis; a primary physician’s approach may depend more heavily on laboratory testing for most musculoskeletal pain symptoms instead of using history and physical examination to identify those patients who require early specialty care.18 Lack of knowledge and practice process problems also cause delayed and inappropriate referral decisions for musculoskeletal disease care more generally, and, in certain cases, increased unnecessary, expensive testing, such as overuse of magnetic resonance imaging for evaluation of acute back pain.16,19-21 Finally, the variations among individual primary physicians in their management of patients can preclude efficiency and optimal outcomes at the health system level.

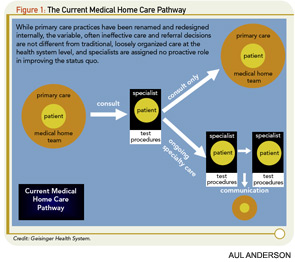

Proactive, interdisciplinary communication is lacking in the current Medical Home model. Multiple studies summarized in a recent metaanalysis suggest that interdisciplinary communication improves chronic disease management.22 While this analysis focused on diabetes and mental health studies, its conclusions can clearly be generalized. Communication is not only important for the care of the individual, it is essential for implementing evidence-based treatment and referral guidelines and for building consensus as to who will do what for whom at the system level.13

The initial experiences, including our own, with the Medical Home have been mixed for managing musculoskeletal diseases. Optimal osteoporosis care has not been supported in systems adopting the Medical Home. At Kaiser Permanente, a highly successful system-based program has been developed instead of using the Medical Home for this purpose.23 Results of a recent study indicate that implementing a Medical Home within the University of Wisconsin Medical Foundation (UWMF) has actually interfered with osteoporosis care that previously was provided effectively and efficiently through a system-based coordination program.24