Leaders in primary care medicine in the U.S. have advocated a model of healthcare delivery called Patient Centered Medical Homes, in which all patients would receive care through primary care practices.1,2 In its realignment of providers, this model calls for major changes in the relationship between primary care providers and specialists. Motivating this initiative are data indicating an association between lower costs and better population health on one hand and more primary physicians and fewer specialists on the other. The association has been documented in health systems of other countries, as well as some areas of the U.S.3-6

Although a cause-and-effect relationship between outcome and provider mix has not been established for the individual patient or for the population, these findings have fueled a drive to create Medical Homes. Pilot testing of this approach is ongoing at present, and has received funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (ARHQ) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Other proposals linked to the Medical Home model include government financing to increase medical school enrollment of primary care providers, forgiving educational loans for primary care physicians, and altering the structure of physician payment mechanisms. Some multispecialty group practices, including our own are implementing this approach even before its effectiveness is established rigorously.

While momentum for the Medical Home model has grown, some physicians and policy experts have questioned the current Medical Home approach and its readiness—indeed, some specialty organizations, including the ACR, have been unwilling to endorse it.7 Concerns about the model include:

- Variable definitions of the Medical Home that may confound the analysis and implementation of this model;8,9

- Unresolved questions about costs and scalability;8

- The complexities and challenges identified in the pilot testing within family practices;10 and

- The lack of evidence for large-scale improvement in outcomes or cost savings.8,9,11

We share these concerns based on our experiences within our own health systems and our work developing system-based rheumatic disease management programs.12,13 As we see it, the central problem in the model concerns the relative roles of subspecialists and primary care Medical Homes in the management of chronic diseases. These diseases account for much of the population morbidity and 70% of healthcare costs in the U.S.14

We are also concerned that our society is being asked to invest time and money in pursuing a solution that seems unlikely on its own to solve the recognized problems that plague healthcare in the U.S. We suggest that system-based chronic disease management is preferable to either traditional healthcare or the Medical Home model.

TABLE 1: Local Health System Requirements for Developing Integrated Chronic Disease Management Programs

- Visionary physician leadership.38-40

- Building consensus among providers.22

- Enhancing communications among providers and patients.14

- Developing a culture of measurement and continuous improvement.41,42

- Shifting from individualism and high process variance to standardization.13,38

- Redesigning the office practice.12,43

- Optimizing patient flow through the health system.16,37,44,45

What Is the Medical Home?

The current Medical Home model proposes that primary care practices should be redesigned as interdisciplinary teams to provide or coordinate all care for all patients, including those needing services for prevention, acute and chronic disease management, and end-of-life care.1 This concept was developed initially during the 1960s in the field of pediatrics; in the past decade, it was expanded to include internal medicine and family medicine as well. The changes considered essential for transforming traditional primary care practices into Medical Homes include:

- Continuous access of patients to a personal physician;

- Responsibility for all of the patient’s acute, chronic disease, preventive, and end-of-life care;

- Coordination of patient care with specialists;

- Adoption of “patient centeredness”; and

- Use of information systems.

Medical Home proposals are generally silent about any active role for specialists in planning or delivering patient care, other than that requested by primary physicians for complex cases and procedures. The American College of Physicians 2006 position paper, “The Advanced Medical Home: A Patient-Centered, Physician-Guided Model for Healthcare,” may have added further confusion by suggesting that, “For most patients, the personal physician would most appropriately be a primary physician, but it could be a specialist or subspecialist for patients requiring ongoing care for certain conditions (e.g., severe asthma,[etc.]).”15

Concerns About Managing Chronic Diseases

We advance the following set of propositions that reflect studies from the literature as well as our personal opinions.

Knowledge and experience of primary care physicians are not sufficient for optimal chronic disease management. In our view, primary physicians often do not possess the depth of knowledge and experience across the spectrum of complex chronic diseases to provide care at the level provided by specialists. Expecting more from primary care providers in the area of traditional subspecialty care is unrealistic. The increase in specialization across a broad range of chronic diseases has been driven not only by an increase in the number, sophistication, and complexity of procedures, but also by the rapid proliferation of knowledge throughout medicine that has led to multiple options for diagnosis and treatment. Advances are too numerous and occur too rapidly for any one physician or specialty to learn about them and then to stay current. This challenge accounts in part for the widely documented problems with diagnosis, timely referral, and optimal treatment, and the 17-year lag to adoption of new discoveries into standard care.14,16 Moreover, the expectation that computer-based decision support will close these gaps seems unrealistic to us.

As one example of the differences in care depending on provider, rheumatology care for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is more effective than primary care, as shown by Catherine MacLean and co-authors in a large insurance company cohort of 1,355 RA patients.17 A yearly physical exam, sedimentation rate, and drug monitoring were provided to 75% of patients receiving rheumatology care and 47% of those managed by primary physicians.

Another example of provider differences in management relates to the initial evaluation of early arthritis; a primary physician’s approach may depend more heavily on laboratory testing for most musculoskeletal pain symptoms instead of using history and physical examination to identify those patients who require early specialty care.18 Lack of knowledge and practice process problems also cause delayed and inappropriate referral decisions for musculoskeletal disease care more generally, and, in certain cases, increased unnecessary, expensive testing, such as overuse of magnetic resonance imaging for evaluation of acute back pain.16,19-21 Finally, the variations among individual primary physicians in their management of patients can preclude efficiency and optimal outcomes at the health system level.

Proactive, interdisciplinary communication is lacking in the current Medical Home model. Multiple studies summarized in a recent metaanalysis suggest that interdisciplinary communication improves chronic disease management.22 While this analysis focused on diabetes and mental health studies, its conclusions can clearly be generalized. Communication is not only important for the care of the individual, it is essential for implementing evidence-based treatment and referral guidelines and for building consensus as to who will do what for whom at the system level.13

The initial experiences, including our own, with the Medical Home have been mixed for managing musculoskeletal diseases. Optimal osteoporosis care has not been supported in systems adopting the Medical Home. At Kaiser Permanente, a highly successful system-based program has been developed instead of using the Medical Home for this purpose.23 Results of a recent study indicate that implementing a Medical Home within the University of Wisconsin Medical Foundation (UWMF) has actually interfered with osteoporosis care that previously was provided effectively and efficiently through a system-based coordination program.24

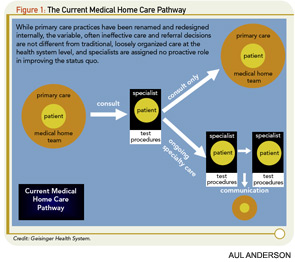

While the goals of the Medical Home are worthwhile, we do not believe that this model adequately addresses the critical problems with patient referral from primary physicians to specialists that are well recognized in traditional healthcare. Figure 1 (above), borrowed from Geisinger Health System’s planning process, outlines its current Medical Home pathway. As currently envisioned, the referral decision is based on the primary physician’s—and often the patient’s—perceptions of the need, timing, and choice of specialty for consultation. In this scenario, the specialist waits passively to be consulted. Only then does he or she provide either advice or ongoing care. The deficiencies of this approach in musculoskeletal disease care have already been reviewed above.

Unaffordable costs and wasteful use of available resources could jeopardize this model. Shortages and maldistributions of services and providers in many U.S. health systems require more efficient use of existing resources if healthcare costs are to decrease and outcomes are to improve. Currently, the primary care work force is often inadequate to implement the Medical Home model, even if teams of physicians, midlevel providers, and nurses are fully utilized. It is not enough to redesign existing primary care practices if, in aggregate, their capacity is insufficient to meet service needs. This situation is true if the practices are asked to take on work that was previously provided by their specialist colleagues, or not at all. Hospitalist programs have exacerbated the shortage of primary physicians by offering physicians an attractive alternative to their currently demanding practice situations. Chronic disease management is further compromised by current and projected shortages of rheumatologists and other nonprocedural subspecialists who share this work with primary physicians, and draw their workforce manpower from the same inadequate pool of trainees.25

Improving outcomes and reducing costs of chronic disease care in the foreseeable future will require effectively utilizing of all of health systems’ existing providers, directing patients to where their care can be provided most effectively, reallocating resources from low- to high-value services, and foregoing the easy and politically correct answer of throwing more resources and dollars at any part of the more globally broken system. We cannot begin to address these urgent problems by waiting years for a train full of new primary physicians to come around the bend.

Implementing the Medical Home model faces other daunting financial barriers and risks. Adding the educational and practice costs for increasing the primary care workforce and implementing the Medical Home to the escalating U.S. healthcare bill is unsupportable, especially in the current economic environment. Projecting future workforce needs based on traditional delivery of care assumptions is flawed. We believe strongly that we should first implement system efficiencies, reduce unnecessary care, and redistribute existing personnel before making these projections.

Proven change management methods also mandate that any proposal as far reaching as the Medical Home should first be tested and refined in clinical improvement pilot projects, and nationally implemented only when, or if, proven. More specifically, we believe that the existing Medical Home pilots should be given sufficient time and resources to determine key process redesigns, resource costs, and the reliability of their evidence-based chronic disease management. Accepting incremental improvements rather than solutions as a basis for change is equally risky.

The Medical Home model could have unintended adverse consequences for primary and specialty physicians. Healthcare redesigns must save physicians time, reduce work, improve patient care, and create equitable and sustainable compensation. The work and costs of managing change must also be considered and compensated. It is not clear that the Medical Home will fulfill these expectations or improve the professional experience of the primary care physician without careful and thoughtful change management and dramatic changes in physician payment mechanisms. Improving primary care compensation without addressing the same problems that plague subspecialists involved in managing chronic diseases is, at best, inequitable. We cannot afford to have a competitive wedge driven between primary care internists and family physicians on one hand and specialty internists on the other. Furthermore, it is not clear that patients with chronic diseases will buy into the Medical Home model either, especially if they sense that their treating specialists are not supporting it, or if their expectations for care are not maintained.

The unintended negative impact of electronic medical records (EMRs) on primary physicians’ workloads is one example of what might compromise implementing the Medical Home in individual practices and local health systems before the concept is tested, refined, and validated. EMR implementation is often launched with insufficient thought to the requirements for practice standardization, consensus and tool building, and changes in workflow. This leads to a physician-centric EMR work model, which is inherently inefficient. As another example of the unintended consequences of premature implementation, the expectation that primary care in the UWMF health system could absorb the coordination of chronic disease care has proven to be unfounded; improved outcomes have not been documented across the spectrum of chronic diseases, and problems with referral management continue as before (JTH personal observations). The prospect of degrading rather than enhancing successful collaborations between primary and subspecialty physicians has also been demonstrated.24

Successes in pediatrics may not translate to adult medicine. In pediatrics, where the Medical Home was first implemented, the mix of preventive, acute disease, and chronic disease service requirements is very different than for adult medicine, as is the mix and distribution of primary care and specialist manpower. These realities make the Medical Home realistic for pediatric care, but they have not obviated the need for more effective management of referrals from primary care to scarce and often remote subspecialists.26 The greater demands for chronic disease management in adults and the different mix of primary physicians and specialists suggest that the pediatric model might not be suitable for adult medicine.

System-based Chronic Disease Management Model

System-based management for chronic diseases organizes patient and disease population care across specialties and over time at the health system level, rather than through any one specialty. This type of model depends on building consensus among all involved providers as to what care is optimal and how it will be organized. Its foundations are evidence-based guidelines and business and resource planning. It relies on disease registries, nurse coordination of care, robust information technology, structured measures of care processes and disease outcomes, and continuous quality improvement. It shifts the emphasis of physician office visits from routine coordination of care that is performed more reliably off-line by others to clinical problem solving for which the physician is uniquely trained. The evolution of programs that meet this definition has been driven by the failures of less structured approaches to achieve effective care productive of excellent, sustainable outcomes. Programs of system-based management have generally evolved in more highly integrated health systems where financial incentives are well aligned, and physician compensation is structured to encourage cooperation.13,27

Multispecialty system-based disease management programs have been implemented for several musculoskeletal diseases and in multiple healthcare environments in the U.S. and other countries.21,23,28-32 They have also been reported for other chronic diseases such as congestive heart failure, diabetes, and mental health problems, among others.22 Such management programs have out- performed traditional care and have generally utilized existing manpower and resources. These experiences suggest that such programs could be disseminated with modest new investments and with immediate impacts on costs and morbidity.12,13 This is where Kaiser Permanente, Geisinger, and other organizations that have already implemented a Medical Home program are heading. We think that this is for the right reasons. It is safe to assume that no increased number of providers and amount of other resources will improve anything if the delivery of care stays the same.

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) have been proposed recently for providing more effective healthcare and shifting how providers are paid from individually through fee-for-service to collectively for “episodes of care.”33,34 CMS is piloting the ACO concept for Medicare within currently integrated health systems, and approaches are being considered for encouraging traditional health systems to evolve into ACOs. The challenges inherent in achieving these changes are well recognized, as is the requirement for effective primary care within ACOs.35 System-based care management for chronic diseases is also required for the success of ACOs, and the Medical Home as currently defined is not sufficient for this task.

The requirements that we consider essential for developing system-based chronic disease programs are listed in Table 1 (p. 17) with informative references related to each. Discussing these requirements in detail is beyond the scope of this article, in which we are focused instead on the advantages of this approach compared with the current Medical Home proposals.

How Do You Stop a Train That Has Already Left the Station?

The Medical Home philosophy is a good one, because its goal is to improve the patient well-being and healthcare experience while simultaneously reducing cost. The Medical Home proposes to do so by taking a holistic approach to the patient, and integrating community resources with medical resources to provide for the total needs of the patient. The problem lies in the management of chronic diseases, where most of the cost and care is done on the specialty side. By not defining the role of the specialist, the Medical Home model in its current design will likely result in restricted or haphazard specialty involvement, and will do nothing in the long term for the cost of care.

Because it appears likely that this model is here to stay in some form, it behooves us to consider, with our knowledge of systems and process redesign, how we can take the Medical Home model to the next level—one where we have successfully integrated specialty care. There is a dearth of information about next steps. Fisher and others have coined the term “medical neighborhood,” implying that the specialists would be a “neighbor” of the Patient Centered Medical Home.36 The designation of a neighbor does not specify the relationship. A neighbor can be someone you may or may not like; you might not invite them to your next party and, when in need, you may either borrow a cup of sugar from your neighbor or you can go to the store. In a neighborhood, the specialist could have a limited or inadequate role, relegated to involvement in patient care only at the behest of the Patient Centered Medical Home. This role is reactive rather than proactive. A more fitting analogy for a new relationship may be the formation of a co-op in which we specialists and our colleagues in primary care work together and are both invested in the efficiency, effectiveness, and outcomes of patient’s and disease populations’ care.

Instead of trying to derail the train, a more effective approach may be to morph the current model into a next iteration. Figure 2 (above) provides some key areas that need to be defined in this new model, including:

- Trigger for Specialty Care: How do we move from a manual process of placing a consult, to a proactive, data-driven approach?

- Mode of Care: How do we move beyond the traditional face-to-face consult to other means of delivering care (such as telemedicine and provider–provider off-line management)?

- Care Pathway: How do we move from gestalt-driven hyper-variable care to using functional and outcome measures and pathways of care with defined roles and responsibilities?

- Communication: How do we move from the phlegmatic communication process where there is a high “noise-to-signal” ratio (a lot of meaningless content, with resulting inability to see what actually needs to be done) to a process that establishes communication guidelines that facilitate transitions and handoffs of care?

Conclusions

Implementing the primary care Medical Home presents daunting problems. Most importantly, we believe that this model in its current form represents an inadequate solution for reducing the costs and improving the outcomes of chronic disease care. In contrast, we propose that integrating this necessary care through system-based accountable programs can be achieved by realigning existing resources and using tested approaches to produce immediate short-term and increasing long-term benefits. Continuous process improvement and industrial work management methods are ideally suited to testing, implementing, and disseminating these positive changes.

The momentum already gained in support of the Medical Home requires that rheumatologists and the ACR become advocates for subspecialty leadership in chronic disease care.37 We believe strongly that we put our patients and our specialty at risk if we do nothing, ignore the current health policy direction, continue to deliver healthcare as has been done for the past 100 years, are not proactively working with our colleagues in primary care to define our role, and do not contribute substantially to redesigning how chronic disease care is implemented. The recently approved ACR Position Statement on the Medical Home is an important first step in the right direction.7

Dr. Harrington is professor in the division of rheumatology at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison. Dr. Newman is director of the department of rheumatology and vice-chair of the division of medicine at Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa.

References

- Patient Centered Primary Care Collaborative. Joint principles of the patient centered medical home. Available at www.pcpcc.net/node/14. Published February 2007. Accessed June 18, 2010.

- Bodenheimer T, Chen E, Bennett HD. Confronting the growing burden of chronic disease: Can the U.S. healthcare workforce do the job? Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:64-74.

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457-502.

- Goodman DC, Grumbach K. Does having more physicians lead to better health system performance? JAMA. 2008;299:335-337.

- Welch WP, Miller ME, Welch HG, Fisher ES, Wennberg JE. Geographic variation in expenditures for physicians’ services in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:621-627.

- Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. Quantifying the health benefits of primary care physician supply in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2007;37:111-126.

- American College of Rheumatology. Position statement: The patient centered medical home. Available at www.rheumatology.org/practice/clinical/position. Published February 2010. Accessed June 18, 2010.

- Sidorov JE. The patient-centered medical home for chronic illness: Is it ready for prime time? Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:1231-1234.

- Carrier E, Gourevitch MN, Shah NR. Medical homes: challenges in translating theory into practice. Med Care. 2009;47:714-722.

- Nutting PA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Jaen CR, Stewart EE, Stange KC. Initial lessons from the first national demonstration project on practice transformation to a patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:254-260.

- Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM. The patient-centered medical home: Will it stand the test of health reform? JAMA. 2009; 301:2038-2040.

- Harrington JT, Newman ED. Redesigning the care of rheumatic diseases at the practice and system levels. Part 1: Practice level process improvement (Redesign 101). Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:S55-S63.

- 13. Newman E, Harrington JT. Redesigning the care of rheumatic diseases at the practice and system levels. Part 2: System level process improvement (Redesign 201). Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:S64-S68.

- Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001.

- American College of Physicians. The Advanced Medical Home: A patient-centered, physician-guided model of healthcare. Available at www.acponline.org/advocacy/where_we_stand/policy/adv_med.pdf. Published January 2006. Accessed June 18, 2010.

- 16. Harrington JT, Walsh MB. Pre-appointment management of new patient referrals in rheumatology: A key strategy for improving healthcare delivery. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45:295-300.

- MacLean CH, Louie R, Leake B, et al. Quality of care for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA. 2000;284:984-992.

- Emery P, Breedveld FC, Dougados M, Kalden JR, Schiff MH, Smolen JS. Early referral recommendation for newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis: Evidence based development of a clinical guide. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:290-297.

- Graydon SL, Thompson AE. Triage of referrals to an outpatient rheumatology clinic: Analysis of referral information and triage. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1378-1383.

- Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2001; 344:363-370.

- Harrington JT, Dopf CA, Chalgren CS. Implementing guidelines for interdisciplinary care of low back pain: A critical role for pre-appointment management of specialty referrals. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2001;27:651-663.

- Foy R, Hempel S, Rubenstein L, et al. Meta-analysis: Effect of interactive communication between collaborating primary care physicians and specialists. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152: 247-258.

- Dell R, Greene D, Schelkun SR, Williams K. Osteoporosis disease management: The role of the orthopaedic surgeon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:188-194.

- Harrington J, Lease J. Primary care compared to system-based coordination of post-fracture osteoporosis care. Arthritis Rheum. 2010: in press.

- Deal CL, Hooker R, Harrington T, et al. The United States rheumatology workforce: Supply and demand, 2005-2025. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:722-729.

- Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Recommendations for improving access to pediatric subspecialty care through the medical home. Available at www.mchb.hrsa.gov. Published December 2008. Accessed June 18, 2010.

- Gawande A. The cost conundrum. The New Yorker. 2009. June 1:36-44.

- McLellan AR, Gallacher SJ, Fraser M, McQuillian C. The fracture liaison service: Success of a program for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:1028-1034.

- Bogoch ER, Elliot-Gibson V, Beaton DE, Jamal SA, Josse RG, Murray TM. Effective initiation of osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment for patients with a fragility fracture in an orthopaedic environment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:25-34.

- Harrington JT, Barash HL, Day S, Lease J. Redesigning the care of fragility fracture patients to improve osteoporosis management: A healthcare improvement project. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:198-204.

- Newman ED, Ayoub WT, Starkey RH, Diehl JM, Wood GC. Osteoporosis disease management in a rural healthcare population: Hip fracture reduction and reduced costs in postmenopausal women after 5 years. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:146-151.

- Newman ED, Matzko CK, Olenginski TP, et al. Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis Program: A novel, comprehensive, and highly successful care program with improved outcomes at 1 year. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:1428-1434.

- Shortell SM, Casalino LP. Healthcare reform requires accountable care systems. JAMA. 2008;300:95-97.

- Fisher ES, McClellan MB, Bertko J, et al. Fostering accountable healthcare: Moving forward in Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:w219-w231.

- Mechanic D. Replicating high-quality medical care organizations. JAMA. 2010;303:555-556.

- Fisher ES. Building a medical neighborhood for the medical home. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:1202-1205.

- Harrington JT. A view of our future: The case for redesigning rheumatology practice. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:716-719.

- Fisher ES, Bynum JP, Skinner JS. Slowing the growth of healthcare costs—lessons from regional variation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:849-852.

- Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining healthcare: Creating value-based competition on results. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press; 2006.

- Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in healthcare. JAMA. 2003;289:1969-1975.

- Phillips LS, Twombly JG. It’s time to overcome clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:783-785.

- Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA. 2008;299:1182-1184.

- Harrington J, Newman E. Streamlining rheumatology practice. Int J Clin Rheumatol. 2010;5:177-185.

- Maddison P, Jones J, Breslin A, et al. Improved access and targeting of musculoskeletal services in northwest Wales: Targeted early access to musculoskeletal services (TEAMS) programme. BMJ. 2004; 329:1325-1327.

- Newman ED, Harrington TM, Olenginski TP, Perruquet JL, McKinley K. “The rheumatologist can see you now”: Successful implementation of an advanced access model in a rheumatology practice. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:253-257.