Rheumatology’s Supply Side

The most important factor affecting the supply of rheumatologists in practice today and in the future is the number completing fellowships each year. The workforce study therefore examined data from adult and pediatric rheumatology fellowships for the past 10 years. Both the number of positions and the number of applicants have increased during this period, and rheumatology has a high rate of fellowship completion overall. There are still a number of existing fellowship positions not filled each year, however, and the overall number of fellows completing programs needs to be even higher to meet the predicted demand.

In the official ACR response to the Workforce Study, Neal S. Birnbaum, MD, president of the ACR said, “The expansion of current training capacity in rheumatology would require not only an increase in salary support for fellows but also meaningful growth in training resources including academic faculty, dedicated space for academic endeavors, and increased clinical opportunities.” In addition, “the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education [ACGME] has created rigorous program requirements that help ensure the quality of training programs to overcome at start-up,” he notes. “In the face of all of these substantial challenges it seems unlikely that we will see any significant growth of rheumatologists entering the workforce anytime soon.”

The specialty has made good use of available training positions. “Our ability to recruit rheumatologists is better than it was 10 years ago and the number of applicants has gone up significantly,” says Walter G. Barr, MD, immediate past chair of the ACR Committee on Training and Workforce Issues, which spearheaded the workforce study advisory group. “There has been a major increase in the quality of those applying.” Dr. Barr contends that managed care’s gatekeeper model was in large part the cause of a move away from rheumatology and other specialties in the last decade. “Students were told by their deans until the late 1990s that managed care would limit their salary abilities,” he says, but the influence of managed care is waning.

Money is certainly an issue for upcoming medical students who have a large debt to repay after graduation, says Christy Park, MD, a young rheumatologist at Northwestern University in Chicago, and a member of the ACR’s young investigators subcommittee. It is also clear, she says, that there are limitations to the expansion of fellowship programs and that one in particular is the challenge of maintaining research funding to establish or support an academic research career. But Dr. Park and other young investigators see a brighter picture for their profession, if not five years out, then seven to 10 years from now.

“There are big sacrifices in the beginning, but overall I am happy with what I am doing and hope that in a few years I will catch up financially,” says Giovanni Franchin, MD, who recently completed his rheumatology fellowship at Columbia University in New York City.

A recent survey of rheumatology fellows across the country shows that these young physicians are happy with their choice but have lingering concerns about financial issues that may arise, says survey author John Fitzgerald, MD, an adult rheumatologist at UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, and a member of the ACR young investigator subcommittee.

Residency and Fellowship Trends

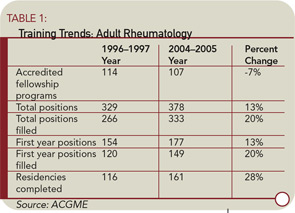

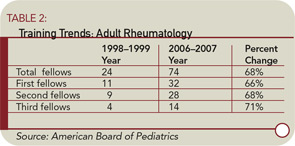

The workforce study takes a retrospective review of adult and pediatric rheumatology positions for the past 10 years, beginning in 1996. See Tables 1 and 2 for a summary of rheumatology training trends.

“In our supply model, our baseline assumption is that rheumatology fellowship positions and fill rates will remain constant at the 2004–2005 level,” according to the workforce study report. “Comparing the number of first-year fellows to the number completing the program between 1996 and 2005 suggests that adult and pediatric rheumatology have a high completion rate, approaching 100%,” says Dr. Birnbaum. “These data indicate that about 161 fellows in adult rheumatology and nine fellows in pediatric rheumatology entered the market in 2005.”

Dr. Birnbaum notes that another important supply issue is the number of international medical school graduates (IMGs) who fill these fellowship programs. The study report shows that the percentage of IMGs has decreased significantly in both adult and pediatric rheumatology from 1997 to 2005, from 52% to 33% among adult fellowships and from 33% to 20% in pediatrics. IMGs represented a high of 63% in the 1998–1999 group of adult fellowships and a high of 57% in the 2000–2001 group of pediatric fellowships.

Dr. Birnbaum says the key question is whether these IMGs remain in the U.S. after completing their residency training. “While we do not have detailed information concerning fellows in rheumatology, per se, based on data from August 2004 reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association [2005;294:1129-1136], about 50% of IMGs are, in fact, U.S. citizens or have permanent residency status across all graduate medical education programs,” the report surmised. “While there is no data on precisely what proportion of IMGs do, in fact, ultimately practice in the United States, the consensus view of experts is that most ultimately do remain in the United States,” the report said. “Based on our discussions with experts at the Bureau of Health Professions and elsewhere, we estimate that about 80% of IMGs practice in the United States,” it concluded.

Insight from Young Investigators

What can longtime rheumatologists do to continue to draw bright young doctors to the specialty? New rheumatologists share similar reasons for making this their life’s work, and two stand out: great scientific cases that intrigued them and wonderful mentors. Dr. Franchin says he came to rheumatology by coincidence: “My original career path was infectious diseases, but during the first year of my residency I had a wonderful mentor and met several rheumatologists who were doing research. The science was new and promising and very interesting to me.”

Dr. Park encourages those in leadership positions in medical schools to “make rheumatology more enticing by using case studies.” During medical school she took an elective course in rheumatology that piqued her interest. “We need to attract candidates to rheumatology early in medical school,” she contends.

Randy Cron, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, had a doctoral degree in immunology when he decided to apply for a pediatric rheumatology fellowship. “It really gives me the opportunity to champion the evaluation and treatment of ailments that make children the victims,” he says. Dr. Cron completed his residency in 1997. Science has continued to improve since then, he notes, making his specialty very rewarding.

Pediatric rheumatology is a relatively new specialty, however, says Dr. Cron, and “one-third of the medical schools in the country do not offer pediatric rheumatology in the curriculum.” The number of role models is limited as well, he notes, and even among the practicing pediatric rheumatologists, as many as half are understaffed and overworked. “That doesn’t make the field attractive,” says Dr. Cron.

Pediatric rheumatology work settings offer additional challenges in recruitment and retention of candidates. “Pediatric rheumatologists must work in an academic medical center and do research,” says Dr. Cron. “Because we work in academia rather than community practice, we also make less money.”

New rheumatologists share similar reasons for making this their life’s work, and two stand out: great scientific cases that intrigued them and wonderful mentors.

Rheumatology’s Strengths Draw Young Docs

Although money is an issue for young rheumatologists, those who have chosen this specialty say it is not the most important issue. Dr. Fitzgerald says his survey of current fellows shows many rheumatologists are torn between working in an academic medical center at the cutting edge of medical research and working in a community practice, where the perception is that working hours are shorter and salaries are higher.

Many young rheumatologists also wonder if they will be able to obtain funding for an academic medical career. “After attracting enthusiastic individuals and providing research training, another limitation is the challenge of maintaining research funding to establish or support an academic research career,” says Dr. Park. “Given the current funding environment, there will be more attrition at this stage than before, without additional support or measures to protect this group, who will need to be responsible for training future rheumatologists.”

Younger investigators are at a disadvantage when it comes to obtaining financial support for research. “In the current funding environment, the money has to go to retain the senior people,” Dr. Park says, “but this means that the junior people get shut out.”

However, upcoming doctors who choose rheumatology for a specialty will have exciting and rewarding work, say Dr. Park and her colleagues. They urge senior leaders to step up efforts to promote the positive aspects of the specialty, such as flexibility for young doctors with a family. As Dr. Franchin points out, rheumatologists do not see emergency patients, so it is possible to have a more flexible schedule. Dr. Fitzgerald says the fellows who responded to his survey noted that family and child care issues, work hours, and mentoring all influenced their specialty choice.

All the young rheumatologists interviewed for this article agree that exposure to the field is critical in making a career choice. Dr. Cron says the ACR is doing more to encourage medical students to come to professional meetings to hear about fellowship opportunities and about transitioning into rheumatology practice. “This is a good time to be a rheumatologist,” says Dr. Park. “We are a valuable commodity, with all of the new treatments and the complexity of new drugs.”

As for the need for continuing emphasis on training for the specialty, senior rheumatologists can also increase their commitment, says Paul Caldron, DO, a rheumatologist in community practice in Paradise Valley, Ariz., who served on the ACR Workforce Study Advisory Group. “Community practices are an excellent base for training,” he says. “We are joining with the University of Arizona to begin fellowship training and we encourage more private practices and academic medical centers to do the same.”

Terry Hartnett is writing the workforce study series.