Figure 1: Bullous lesions on the finger extending to the elbow.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a heterogeneous disease associated with multiple acute or chronic cutaneous manifestations, including the relatively rare category of bullous lupus. The development of vesiculo-bullous lesions may be associated with a high morbidity, hence they warrant an urgent investigation, including a skin biopsy to identify the diagnosis and initiate prompt treatment.

With this case, we are going to describe the occurrence of progressive bullous skin lesions in the absence of fever and leukocytosis in a patient with known SLE and discoid lupus on immunosuppressive therapy. This case highlights the importance of considering a broad differential diagnosis as the treatment can be vastly different.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is caused by an exotoxin released by the Staphylococcal bacteria. It attacks the desmosomes, causing detachment of the epidermal layer.

Case

A 46-year-old African-American woman was diagnosed with SLE and discoid lupus in 1999. She was being treated with hydroxychloroquine 400 mg, prednisone 35 mg, mycophenolate mofetil 1,000 mg and cyclosporine 100 mg daily at the time of presentation. She had previously been unresponsive to rituximab and belimumab.

The patient presented to the hospital with generalized malaise, polyarthralgia, alopecia and acute worsening of her chronic skin disease with a flare of her malar rash and discoid lesions on the face, chest, hands and feet. On presentation, she was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. Blood work revealed anemia, lymphopenia with normal liver and renal function and a normal urinalysis. She had reduced complement levels—the C3 was 32.1 mg/dL (normal 83–193 mg/dL), and the C4 was 2.9 mg/dL (normal 15–53 mg/dL)—and an elevated anti-ds-DNA (87 IU/mL) (normal

Given the severity and the extent of her skin lesions, she was started on pulse-dose intravenous steroids. She had responded well to this therapy in the past. High-dose steroids led to resolution of some lesions, but within a few days, new lesions appeared, involving her limbs, abdomen and thighs (see Figure 1), with morphological evolvement of the rash to form painful desquamating bullous lesions filled with serous fluid. The malar rash did involve the naso-labial fold (see Figures 2a, 2b). Nikolsky’s sign was positive. There was also purulent discharge from both eyes, with inflammation of the iris, and bullous lesions were visible on the external ear. Importantly, there was the notable absence of oropharyngeal or vaginal mucosal involvement.

Figures 2a and 2b: Vesiculo-bullous lesions on the face and neck after the patient received steroids on admission.

Given the evolution of her skin lesions despite steroids, the differential diagnosis included infectious vs. autoimmune conditions, such as bullous lupus, which can be resistant to steroid treatment. Dapsone was initiated while awaiting the result of skin biopsies.

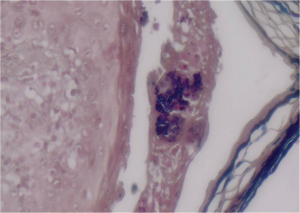

Figure 3: (Gram stain 60x) Gram-positive cocci aggregated in colonies within the vesicle.

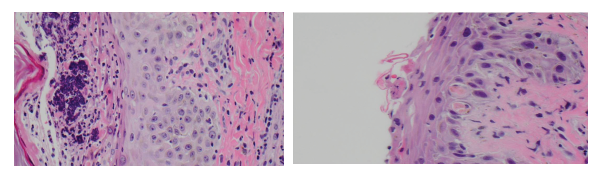

Microbiological examination of serous fluid from the cutaneous blisters grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (see Figure 3). Histopathology from the skin biopsies revealed the presence of interface vacuolar dermatitis (see Figure 4) with cytoid bodies, as can be seen in autoimmune conditions and superficial and mid epidermal acantholysis (see Figures 5 and 6), for which the differential diagnoses were pemphigus foliaceous and Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Direct immunofluorescence showed a continuous granular reaction for both IgG and IgM at the dermo-epidermal junction (positive lupus band). ELISA was negative for Desmoglein 1 and 3. The final pathology result suggested a combined presence of a flare of lupus erythematosus with a Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

The patient was receiving intravenous and topical antibiotics including coverage for MRSA, but given the lack of an immediate response, she went on to receive intravenous immunoglobulins, which led to a significant improvement of her rash (see Figure 7).

Discussion

Acute-onset bullous lesions in any patient need to be addressed with due caution, with considerable emphasis on ruling out life-threatening dermatological emergencies, such as Stevens Johnson syndrome (SJS) or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and consideration of an infectious etiology (especially in patients on immunosuppressive therapy) or other autoimmune conditions, such as pemphigus. Given the extent of overlapping clinical symptoms of bullous lesions, a skin biopsy is critical because a careful histopathological examination and immunohistochemical staining are essential to confirm the diagnosis.

Lupus can present with a wide variety of cutaneous manifestations, ranging from papules and plaques to vesiculo-bullous lesions.1,2 Acute cutaneous lupus can present as an erythematous malar rash typically sparing the nasolabial fold and can evolve into vesiculo-bullous lesions.2,3

(left) Figure 4: (H&E 60x) Interface vacuolar dermatitis and a superficial vesicle with neutrophils and bacterial colonies.

(right) Figure 5: (H&E 60x) Interface vacuolar dermatitis with two cytoid bodies; note the superficial acantholysis of the epidermal cells.

Subacute cutaneous lupus involves the upper neck, chest, back and the extensor surfaces of arms and forearms, sparing the scalp and knuckles, and manifests as papules or annular plaques. This condition is rarely associated with systemic manifestations. Chronic cutaneous lupus or discoid lupus manifests as coin-shaped lesions with a hypopigmented center.2,3

Bullous lupus is relatively rare—described in 1–8% of patients.4,5 Bullous lupus is caused by the development of antibodies against type VII collagen in the basement membrane and manifests with tense, subepidermal vesiculo-bullous eruptions on an erythematous base, more commonly seen on the trunk, face and upper extremities.5 Immunofluorescence reveals continuous or granular pattern of deposition along the dermo-epidermal junction extending to the dermis.

A 2015 clinic-pathological study described blistering lesions in 22 patients with SLE and, based on their histological description, divided them into three groups.6 One group included five patients with extensive epidermal necrosis appearing as TEN-like lesions. A second group of nine patients had classic cutaneous findings, with interface dermatitis with vacuolization of the basal keratinocytes and lymphocytic infiltrate. The third group of eight patients had neutrophilic bullous lesions.

(left) Figure 6: (H&E 60x) Interface vacuolar dermatitis with diffuse acantholysis; note the superficial layer has exfoliated.

(right) Figure 7: Healing lesions after treatment with antibiotics and intravenous immunoglobulins.

SJS and TEN also present as bullous lesions and are dermatological emergencies that usually occur with exposure to new drugs (including disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs [DMARDs], such as TNF-alpha inhibitors). However, these conditions usually involve larger body surface area and affect the mucus membranes. Our patient did not have a history of an exposure to a new drug or any other identifiable environmental triggers. She also did not experience any mucosal involvement, making SJS or TENs a less likely possibility.

Studies have described increased morbidity and mortality secondary to infections in SLE patients on immunosuppressive therapy, with a high likelihood of staphylococcal organism involvement due to functional neutrophil dysfunction.7-9 Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is caused by an exotoxin released by the bacteria. It attacks the desmosomes, causing detachment of the epidermal layer. It manifests as painful flaccid blisters, positive for Nikolsky’s sign, with widespread desquamation. This disease is more common in children and infants; however, it is associated with mortality rates in adults of approximately 60%, depending on comorbid conditions, degree of immune suppression and delay of treatment initiation.10,11

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome causing bullous lesions in a patient with SLE is, however, rare. In our case, we believe the source of infection was possibly the super-infection of the preexisting skin lesions and the nares being the site of colonization for MRSA.

Our review of literature revealed a case of Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome described in a patient with lupus nephritis, attributed to reduced toxin excretion by the kidneys, as observed in animal models; however, our patient had normal renal function.12 There has also been infrequent case report description of systemic manifestations of toxic shock syndrome without cutaneous involvement in postsurgical or postpartum lupus patients.13,14

Management of Staphylococcal scalded syndrome includes appropriate antibacterial coverage and intravenous hydration. Given the syndrome’s rarity and severity, this case emphasizes the importance of considering Staphylococcal scalded syndrome in the differential diagnosis of bullous lesions in a patient with SLE.

Mitali Sen, MD, is a second-year internal medicine resident at Albert Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia.

Corrado Minimo, MD, is the attending physician in the Department of Pathology at Albert Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia.

Ruchika Patel, MD, is the attending physician in the Department of Rheumatology at Albert Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia.

References

- Crowson A, Magro C. The cutaneous pathology of lupus erythrematosus: A review. J Cutan Pathol. 2001 Jan;28(1):1–23.

- Rothfield N, Sontheimer R, Bernstein M, et al. Lupus erythrematosus: Systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006 Sep–Oct;24(5):348–362.

- Yell JA, Mbuagbaw J, Burge SM. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythrematosus. Br J Dermatol. 1996 Sep;135(3):355–362.

- Duan L, Chen L, Zhong S, et al. Treatment of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:167064.

- Contestable J, Edgehard K, Meyerle J, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythrematosus: A review and update to diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014 Dec;15(6):517–524. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0098-0.

- Merklen-Djafri C, Bessis D, Frances C, et al. Blisters and loss of epidermis in patients with lupus erythematosus: A clinico-pathological study of 22 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015 Nov;94(46):e2102.

- Gladman DD, Hussain F, Ibañez D, et al. The nature and outcome of infection in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2002;11(4):234–239.

- Gresham HD, Ray CJ, O’Sullivan FX. Defective neutrophil function in the autoimmune mouse strain MRL/lpr. Potential role of transforming growth factor-beta. J Immunol. 1991 Jun 1;146(11):3911–3921.

- Caver TE, O’Sullivan FX, Gold LI, et al. Intracellular demonstration of active TGFbeta1 in B cells and plasma cells of autoimmune mice. IgG-bound TGFbeta1 suppresses neutrophil function and host defense against Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Clin Invest. 1996 Dec 1;98(11):2496–2506.

- Patel GK, Finlay AY. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: Diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4(3):165–175.

- Patel GK. Treatment of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2004 Aug;2(4):575–587.

- Rydzewska-Rosolowska A, Brzosko S, Borawski J, et al. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in the course of lupus nephritis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2008 Jun;13(3):265–266.

- Huseyin TS, Maynard JP, Leach RD. Toxic shock syndrome in a patient with breast cancer and systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001 Apr;27(3):330–331.

- Kadoya A, Iikuni Y, Hosaka S, et al. A SLE case with toxic shock syndrome after delivery. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1996 Dec;70(12):1279–1783.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of the following in the preparation of this article: Sandra Schwarcz, DO, and Jose Nitram-Aliling, MD, fellows in the Department of Rheumatology at Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia. The pictures were produced with the patient’s permission, and they thank her for allowing the same.