Andrey_Popov/shutterstock.com

We report a case of a 27-year-old woman who was initially diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), had features of scleroderma and was subsequently found to have lymph node biopsy consistent with multicentric Castleman disease (MCD). She also had serologic evidence of acute Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection (vs. reactivation of EBV). The occurrence of MCD in association with SLE and scleroderma is rare, and the relationship between these diseases and EBV remain areas of ongoing research. We report this case to increase awareness of this potential diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma.

Case

The patient is a 27-year-old African Caribbean woman who initially presented with malaise, dry cough, weight loss of 25 lbs. over four months, diffuse arthralgia, myalgia, hair loss, diaphoresis, numbness of extremities, bilateral ankle swelling, cold intolerance and Raynaud’s phenomenon. She was febrile, temperature 101.8º F, blood pressure of 102/57 mmHg, pulse of 111 bpm and respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute. On physical exam she was cachectic, with tightness around the mouth, telangiectasia over the nasal bridge, digital ulcer on the left third digit, soft abdomen with hepatosplenomegaly, pitting edema of the lower extremities, bilateral axillary and femoral lymphadenopathy.

Labs were significant for hemoglobin (Hb) of 5.6 g/dL (normal range: 12–16 g/dL), a reticulocyte count of 3.11% (normal range: 0.5–2.9%), LDH 664 U/L (normal range: 135–214 U/L), haptoglobin of 3 mg/dL (normal range: 30–200 mg/dL), ferritin 589.7 ng/mL (normal range: 10–291 ng/mL), direct Coombs test positive for nonspecific cold agglutinin, an unremarkable peripheral blood smear and an ESR of 129 mm/hr (normal range: 0–20 mm/hr). She had an albumin of 2.6 g/dL (normal range: 2.8–5.7 g/dL) and 2+ proteinuria on dipstick. RF, ANA and c-ANCA were negative, but p-ANCA was positive. C3 was 45 mg/dL (normal range: 86–184 mg/dL) and C4 was 7 mg/dL (normal range: 20–58 mg/dL). HIV, human T cell lymphoma virus 1 (HTLV 1), hepatitis B and C screening, RPR, PPD and blood cultures were negative.

A non-contrast CT scan of the chest revealed bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy measuring up to 1.5 cm, trace bilateral pleural effusions and small pericardial effusion, but no consolidation. A CT scan of the abdomen with contrast revealed bulky retroperitoneal and pelvic lymphadenopathy with bulky external iliac nodes, the largest of which was 4.4 x 1.7 cm, ascites, hepatosplenomegaly, periportal edema, perihepatic ascites and pericholecystic fluid. 2D echo revealed an ejection fraction of 55–60%, mild tricuspid regurgitation, estimated pulmonary arterial pressure of 40 mmHg and a small to moderate pericardial effusion.

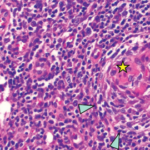

Figure 1

Due to lymphadenopathy and concern for lymphoma, an inguinal lymph node biopsy was performed by interventional radiology, but was non-diagnostic.

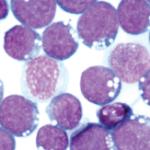

A bone marrow biopsy was performed and revealed normocellular bone marrow for the patient’s age.

Flow cytometry revealed no phenotypic evidence of blasts, myeloid dysmaturation, T cell lymphoma or plasma cell dyscrasia. Due to a domestic concern arising at this time, the patient signed out of the hospital against medical advice.

Two days later, she presented with night sweats and altered mental status (AMS). She had borderline low blood pressure of 91/60 mmHg and hypoxia with oxygen saturation of 70%. A CT angiogram was performed, which ruled out pulmonary embolism. The patient had an adequate response to fluid resuscitation. A CT scan of the head with and without contrast and lumbar puncture were negative; however, her AMS worsened and the patient was noted to laugh inappropriately and hear voices.

Figure 2

An excisional lymph node biopsy was performed and the autoimmune workup was repeated, because the clinical picture was consistent with SLE and scleroderma. The ANA came back positive with quantitative level of 638 IU/mL; anti-ds DNA, anti-SSB, anti-Sm, anti-RNP and anti-histone antibodies were also positive. Anti-Jo 1 was equivocal, and the anti-centromere, anti-SCL-70 and anti-RNA polymerase III were negative. Her serum protein electrophoresis revealed an elevated polyclonal spike suggestive of inflammatory process.

In light of the patient’s altered mental status, negative CNS workup, positive ANA, anti-ds DNA and anti-Sm, SLE with lupus cerebritis was diagnosed.

The patient was treated with pulse steroid therapy, followed by high-dose steroids, with moderate improvement in mental status and resolution of fever.

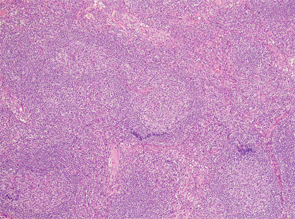

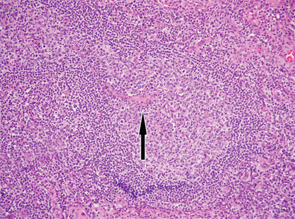

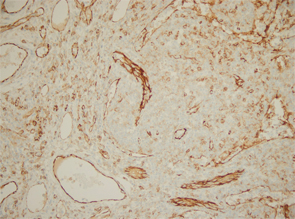

Excisional biopsy of a left inguinal lymph node. 1) Low magnification shows preserved architecture of the lymph node. 2) A germinal center with a central hyalinized vessel (arrow), giving a lollipop appearance. 3) Immunostaining using an endothelial cell marker, CD31, highlights the blood vessels.

Of note, the patient had digital ulceration and Raynaud’s phenomenon. An echocardiogram suggested pulmonary hypertension. The excisional lymph node biopsy revealed reactive lymphadenitis with features of MCD (see Figures 1–3, opposite). The lymph node specimen was negative for human herpes virus 8 (HH8). EBV IgM and IgG, as well as PCR, were positive.

The patient was treated with the IL-6 inhibitor, siltuximab. After the first dose of siltuximab, the patient had significant improvement of her mental status, and her overall performance returned back to her baseline. She continued to receive siltuximab as an outpatient, but did not follow up with the rheumatology clinic.

Seven months later, she was readmitted for cellulitis of the right arm and found to have a neck mass and a new systolic murmur, and was noted to have pitted scars on her fingertips; at that point, she fulfilled the 2013 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for systemic sclerosis. A CT of her neck revealed persistent lymphadenopathy, and a 2D echo showed persistently elevated pulmonary arterial pressure of 44 mmHg.

Discussion

We present the case of a patient with newly diagnosed SLE and MCD and who also has evidence of EBV reactivation and features of systemic sclerosis.

Castleman disease is a heterogeneous group of disorders with three histological types (i.e., hyaline vascular, plasma cell and mixed) and two clinical subtypes (i.e., localized and multicentric).1 Most cases of MCD occur in middle-aged men, and there is an association between MCD and HIV and human herpes virus 8.2,3 SLE, however, occurs mainly in women of childbearing age. The most common lymph node lesions in SLE are follicular hyperplasia and coagulative necrosis, with the latter being more specific.4

In one review of 33 SLE patients, lymph node pathology consistent with Castleman disease was found in 10% of these patients.4 The reported cases of concomitant MCD and SLE were mainly young to middle-aged women who were HIV negative, like our patient.5-10 Our patient was also noted to have evidence of EBV infection with IgM and IgG antibodies, as well as EBV DNA detected on PCR. These findings suggest that either her EBV infection was subacute or she was reinfected with EBV.11

EBV occurs worldwide, with over 80% of individuals older than 30 being infected. The infection persists for life and is associated with the development of malignancies, such as Burkitt’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s disease and lymphoproliferative disorders.12 EBV has been reported in association with Castleman disease in variable frequencies, ranging from 2 out of 20 to 19 out of 20 cases.13,14 In one instance, EBV was reported to occur in MCD, with fatal results.15

IL-6 may be produced in an autocrine fashion from EBV-transformed B cells.16 Excessive IL-6 production in mice produces a syndrome characterized by anemia, transient granulocytosis, splenomegaly, hypoalbuminemia and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, which closely resembles the systemic features of Castleman disease.17 The level of IL-6 produced by hyperplastic lymph nodes in patients with Castleman disease is directly related to the severity of clinical features and worsening of the lab results, which resolved with the removal of the lymph nodes.18

James et al showed that there is an association between SLE and EBV exposure.19 Further, SLE patients have dysregulated immune responses to EBV, with EBV antigens exhibiting molecular mimicry with common SLE antigens.21 EBV antigens may give rise to autoimmunity in SLE.21,22 There are also impaired T CD8+T cell and cytokine responses to EBV.21 Some SLE patients may also have increased reactivations of EBV.21 Given the global infectious burden, however, EBV likely contributes only a small portion to the risk of SLE, with other genetic and environmental factors playing a role.

Our patient developed autoantibodies characteristic of SLE over a short period of time, which is unusual. Most data show that developments of autoantibodies precede the development of symptoms in SLE by years. In a study by Arbuckle et al, patients were positive for at least one SLE autoantibody for an average of 3.3 years before diagnosis and as early as 9.4 years. Autoantibody formation tends to follow a predictable course, with the accumulation of antibodies prior to the development of symptoms. Notably, anti-Smith and RNP are the antibodies found closest to disease presentation, occurring approximately 1.2 years before disease presentation.20

Our patient had skin tightening of her face and fingers (distal to the metacarpophalangeal joints), a tight oral aperture, telangiectasia, Raynaud’s phenomenon, digital ulcers, pitting scars on her fingertips and pulmonary hypertension by echocardiogram at presentation. Her anti-centromere, anti-scleroderma 70 and anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies were negative. She did not fulfill the 2013 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for scleroderma; however, it will not be surprising if she goes on to develop scleroderma in the future.

We treated her with an IL-6 inhibitor because she had an incomplete response to steroids.23 She improved; however, she did not follow up with the rheumatology clinic.

We report a rare case of MCD in a patient with SLE and scleroderma overlap. This case raises unanswered questions: Is this a random concomitant occurrence of Castleman disease and autoimmune disease or is this a continuum of one disease? Does the associated infection with EBV play a role in linking these diseases? This is an area that needs further exploration.

Kwabna Parker, MBBS, is a fellow at The State University of New York Health Science Center at Brooklyn—better known as SUNY Downstate Medical Center—in the Division of Rheumatology.

Kwabna Parker, MBBS, is a fellow at The State University of New York Health Science Center at Brooklyn—better known as SUNY Downstate Medical Center—in the Division of Rheumatology.

Sireesha Datla, MD, is a fellow at SUNY Downstate Medical Center in the Department of Hematology and Oncology.

Sireesha Datla, MD, is a fellow at SUNY Downstate Medical Center in the Department of Hematology and Oncology.

Nancy Soloman, MD, is a rheumatology attending at SUNY Downstate Medical Center.

Nancy Soloman, MD, is a rheumatology attending at SUNY Downstate Medical Center.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following for their assistance in developing this article: Robert Lewis, MD, Hematology and Oncology Division, SUNY Downstate Medical Center; Jinli Liu, MD, Pathology Department, SUNY Downstate Medical Center; Chuanyong Lu, MD, Pathology Department, SUNY Downstate Medical Center; Priya Chokshi, MD, PGY-3, SUNY Downstate Medical Center; and Manile Dastagir, DO, PGY-3, SUNY Downstate Medical Center.

References

- Maslovsky I, Uriev L, Lugassy G. The heterogeneity of Castleman disease: Report of five cases and review of the literature. Am J Med Sci. 2000 Oct;320(4):292–295.

- Robinson D Jr., Reynolds M, Casper C, et al. Clinical epidemiology and treatment patterns of patients with multicentric Castleman disease: Results from two US treatment centres. Br J Haematol. 2014 Apr;165(1):39–48.

- Saeed-Abdul-Rahman I, Al-Amri AM. Castleman disease. Korean J Hematol. 2012 Sep;47(3):163–177.

- Kojima M, Motoori T, Asano S, Nakamura S. Histological diversity of reactive and atypical proliferative lymph node lesions in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Pathol Res Pract. 2007;203(6):423–431.

- Van de Voorde K, De Raeve H, De Block CE, et al. Atypical systemic lupus erythematosus or Castleman’s disease. Acta Clin Belg. 2004 May–Jun;59(3):161–164.

- Xia JY, Chen XY, Xu F, et al, A case report of systemic lupus erythematosus combined with Castleman’s disease and literature review. Rheumatol Int. 2012 Jul;32(7):2189–2193.

- Kojima M, Nakamura S, Itoh H, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) lymphadenopathy presenting with histopathologic features of Castleman disease: A clinicpathologic study of five cases. Pathol Res Pract. 1997;193(8):565–571.

- Suwannaroj S, Elkins SL, McMurray RW. Systemic lupus erythematosus and Castleman’s disease. J Rheumatol. 1999 Jun;26(6):1400–1403.

- Gholke F, Märker-Hermann E, Kanzler S, et al. Autoimmune findings resembling connective tissue disease in a patient with Castleman’s disease. Clin Rheumatol. 1997 Jan;16(1):87–92.

- Hosaka S, Kondo H. [Three cases of Castleman’s disease mimicking the features of collagen disease]. [Article in Japanese] Ryumachi. 1994 Feb;34(1):42–47.

- De Paschale M, Clerici P. Serological diagnosis of Epstein- Barr virus infection: Problems and solutions. World J Virol. 2012 Feb 12;1(1):31–43.

- Serraino D, Piselli P, Angeletti Cl, et al. Infection with Epstein-Barr virus and cancer: An epidemiological review. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2005 Jan-Jun;19(1–2):63–70.

- Al-Maghrabi JA, Kamel-Reid S, Bailey DJ. Lack of evidence of Epstein-Barr virus infection in patients with Castleman’s disease. Molecular genetic analysis. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2006 Oct;11(4):279–283.

- Chen CH, Liu HC, Hung TT, Liu TP. Possible roles of Epstein-Barr virus in Castleman disease. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009 Jul 9;4:31.

- Yamac K, Senol E, Ataoglu O, Fen T. A case report of multicentric Castleman’s disease with simultaneous Epstein-Barr virus infection. Tumori. 2001 Sep–Oct;87(5):343–345.

- Yokoi T, Miyawaki T, Yachie A, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-immortalized B cells produce IL-6 as an autocrine growth factor. Immunology. 1990 May;70(1):100–105.

- Brandt SJ, Bodine DM, Dunbar CE, Nienhuis AW. Dysregulated interleukin 6 expression produces a syndrome resembling Castleman’s disease in mice. J Clin Invest. 1990 Aug;86(2):592–599.

- Yoshizaki K, Matsuda T, Nishimoto N, et al. Pathogenic significance of interleukin-6 (IL-6/BSF-2) in Castleman’s disease. Blood. 1989 Sep;74(4):1360–1367.

- James JA, Neas BR, Moser KL, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in adults is associated with previous Epstein-Barr virus exposure. Arthritis Rheum. 2001 May;44(5):1122–1126.

- Arbuckle MR, McClain MT, Rubertone MV, et al. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2003 Oct 16;349(16):1526–1533.

- James JA, Robertson JM. Lupus and Epstein-Barr. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012 Jul;24(4):383–388.

- Harley JB, James JA. Epstein-Barr virus infection induces lupus autoimmunity. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2006;64(1–2):45–50.

- Liu YC, Stone K, van Rhee F. Siltuximab for multicentric Castleman disease. Expert Rev Hematol. 2014 Oct;7(5):545–557.