Ipilimumab (Yervoy) is a monoclonal antibody directed against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4). It was the first drug to demonstrate a survival benefit in advanced melanoma and was approved by the FDA in 2011.1 By blocking the CTLA-4 receptor, ipilimumab enhances the immune response against tumors via cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation and proliferation.2 However, immunopotentiating therapy carries the risk of immune-related adverse events (irAEs).

The most common irAEs secondary to ipilimumab include dermatitis, diarrhea, colitis and hypophysitis. Here, we report a case of immune-related aortitis caused by ipilimumab and successful management with systemic corticosteroid therapy, thus far.

Case Presentation

A 51-year-old Caucasian female with pathologic stage IIIB malignant melanoma diagnosed in March 2016 underwent wide radical resection followed by left axillary radical lymph node dissection. She was started on adjuvant treatment with ipilimumab at 10 mg/kg and received three cycles, with one dose every three weeks.

After she was started on ipilimumab, she complained of a generalized pruritic rash and flu-like symptoms, including fever, chills and body aches, that progressively worsened after each cycle of ipilimumab. After her third cycle of ipilimumab, she had developed a diffuse rash that required hospital admission in August.

Biopsy of the rash revealed minimal perivascular dermatitis with dermal hemorrhage and no evidence of vasculitis. Laboratory evaluation was unremarkable and notable for normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, undetectable cryoglobulins and negative for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-myeloperoxidase, anti-proteinase 3 and antinuclear antibodies. Etiology of the rash was thought to be immune-related dermatitis from ipilimumab.

Her rash resolved with a three-week course of oral prednisone. At this time, the decision was made to discontinue further treatment with ipilimumab.

At the end of September, the patient underwent a restaging whole-body PET scan to rule out recurrence or metastasis of melanoma and the results were unremarkable.

At the end of October, which was two months after her last dose of ipilimumab, she complained of worsening fatigue, fever, chills, body aches, generalized abdominal pain, joint pain with swelling of her hands, knees and ankles, nausea, vomiting, headaches and orthostatic symptoms that had progressed over several weeks.

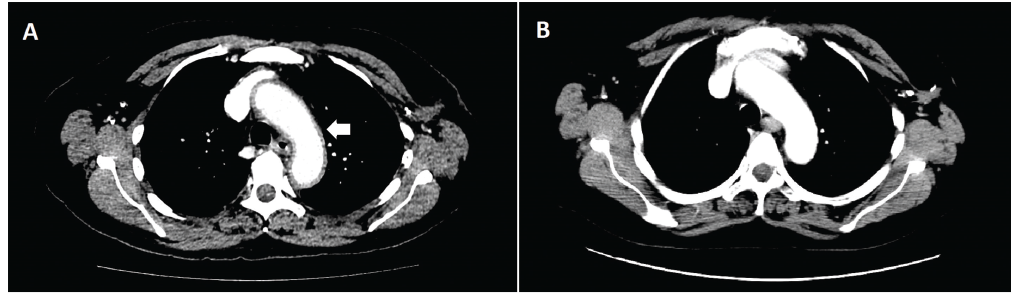

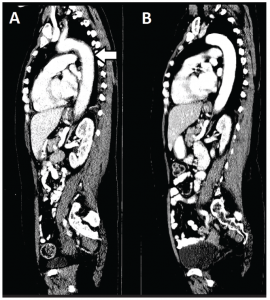

Physical examination was remarkable for hypotension (86/58 mmHg) and tenderness to palpation of the left and right lower quadrants of her abdomen. Laboratory studies revealed normocytic anemia (Hgb 10.4 g/dL), hyponatremia (Na 128 mEq/L), decreased AM cortisol (1.1 ug/dL), decreased ACTH (A CT of the abdomen and pelvis was ordered to rule out colitis and to visualize the adrenal glands. Incidentally, imaging revealed diffuse aortic wall thickening and periaortic inflammation involving the thoracic aorta, origins of neck vessels and abdominal aorta consistent with aortitis (see Figure 1 & Figure 2). The CT also showed findings of bilateral lower lobe patchy airspace opacities, bilateral trace pleural effusions and pericardial effusion. She was started on prednisone 1 mg/kg daily for immune-related aortitis related to ipilimumab.

(click for larger image)

Figure 1: An axial CT image of the chest revealed diffuse aortic wall thickening and periaortic inflammation involving the thoracic aorta, origins of neck vessels, and abdominal aorta consistent with aortitis at time of presentation (Panel A). Inflammation involving the aortic arch can be seen here (white arrow). A follow-up CT one month later (Panel B) reveals near-complete resolution of aortitis after systemic corticosteroid therapy.

Within days of initiation of treatment with steroids, she experienced significant improvement in her symptoms and was discharged home with prednisone 60 mg by mouth daily. Outpatient rheumatology referral was then requested.

At the time of her initial outpatient appointment, the patient had been treated with prednisone 60 mg daily for one week and then tapered to 50 mg daily by oncology for one month. A repeat CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis at this time point revealed near-complete resolution of the soft tissue diffuse wall thickening of the thoracic aorta, with only minimal thickening at the aortic arch. There was also resolution of the lower lobe patchy airspace opacities, pleural effusions and pericardial effusion.

The plan was to taper the prednisone by 10 mg every two weeks to a dose of 20 mg daily. However, the patient self-tapered her prednisone and discontinued the prednisone after another four weeks.

Two weeks after she stopped her prednisone taper, she experienced a recurrence of her previous symptoms and was promptly placed back on prednisone 20 mg daily. Currently, she is undergoing a slower taper of prednisone, and her symptoms are well controlled. If she experiences recurrent symptoms, the plan would be to treat with infliximab, given reports of successful treatment of other irAEs with this drug.

Prolonged steroid taper may be necessary with severe immune reactions & mirrors our treatment of other large vessel vasculitis with regard to prednisone dosing.

Discussion

(click for larger image)

Figure 2: A sagittal CT image of the chest, abdomen and pelvis reveals the extent of aortitis (white arrow) at time of presentation (Panel A) and one month later with systemic corticosteroid therapy (Panel B).

Immune-checkpoint-blocking antibodies have been successful in treating advanced melanoma. The FDA has approved four immune checkpoint inhibitors: ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4), nivolumab [anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (anti-PD-1)], pembrolizumab [anti-programmed death-

ligand 1 (anti-PD-L1)] and atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1).3 However, enhancement of the immune response against tumors can also induce a wide spectrum of irAEs that may require discontinuation of therapy.

Cases of polymyalgia rheumatica, giant cell arteritis, and ovarian and uterine lymphocytic vasculitis have been reported.4,5 Cardiotoxicity has been reported as an irAE, with presentions including myocarditis, pericarditis with pericardial effusion, cardiomyopathy and heart failure.6-8 However, involvement of the aorta has not been reported in the literature to date, and to our knowledge, this is the first reported case of immune-related aortitis caused by ipilimumab or other immune checkpoint inhibitors.

On average, the elimination half-life of ipilimumab is 14.7 days.1 However, delayed presentations of irAEs can occur weeks to months after cessation of treatment. In one report, a dermatologic irAE secondary to ipilimumab presented more than two months after the patient had received their last dose of ipilimumab.9

Our patient developed aortitis two months after her last dose of ipilimumab. In reviewing the literature, it is currently unknown when a patient’s risk of experiencing irAEs ends. Even though our patient’s ipilimumab had been stopped two months prior, she presented with two irAEs concurrently (adrenal suppression and aortitis), along with bilateral lower lobe patchy airspace opacities, pleural effusions and pericardial effusion. Therefore, we recommend that patients closely follow up with their prescribing physician to monitor for complications, possibly for up to a year.

Thirty-five percent of patients who experience an irAE will require systemic corticosteroid treatment. Thirty percent of the aforementioned patients will require additional immunosuppressive therapy, such as infliximab or mycophenolate mofetil.10,11 The package insert for ipilimumab instructs systemic corticosteroids at a dose of 1 to 2 mg/kg/day for severe irAEs. However, it does not specify duration of treatment.12

Our patient was self-tapered off prednisone over eight weeks. However, eight weeks proved inadequate; she had a relapse of her symptoms shortly after stopping prednisone. This information is also helpful in understanding that prolonged steroid taper may be necessary with severe immune reactions and mirrors our treatment of other large vessel vasculitis with regard to prednisone dosing.

Current expert opinion recommends treatment with infliximab if the patient does not respond to corticosteroids promptly, fails a course of appropriately tapered corticosteroids or if there is a relapse while on corticosteroids.13,14

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have described the first case of aortitis secondary to ipilimumab therapy as an irAE. This patient also had manifestations of fatigue, chills, body aches and arthritis accompanied by patchy airspace opacities, bilateral trace pleural effusions and pericardial effusion on imaging. Immune-related aortitis can have a delayed presentation, occurring months after ipilimumab has been stopped. It also can present with vague symptomatology, making it difficult to diagnose if another irAE is present as well. Finally, it can be potentially fatal if untreated, eventually leading to aortic rupture.

Physicians must be aware of the possibility of a patient’s developing aortitis as an irAE secondary to ipilimumab therapy. Early diagnosis and prompt management with systemic corticosteroid therapy are critical to avoiding a potentially fatal outcome.

Byung Hoon Ban, DO, is a first-year internal medicine physician in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. He aspires to become a clinical rheumatologist after he completes his residency.

Byung Hoon Ban, DO, is a first-year internal medicine physician in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. He aspires to become a clinical rheumatologist after he completes his residency.

Jayne Littlejohn Crowe, MD, completed her rheumatology training at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, and now works at Erlanger Health Systems and serves as an assistant professor in the Department of Rheumatology at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

Jayne Littlejohn Crowe, MD, completed her rheumatology training at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, and now works at Erlanger Health Systems and serves as an assistant professor in the Department of Rheumatology at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

Robert Matthew Graham, MD, completed his hematology-oncology fellowship at Wake Forest University, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, N.C. He now serves as the division chief of hematology-oncology and as an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

Robert Matthew Graham, MD, completed his hematology-oncology fellowship at Wake Forest University, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, N.C. He now serves as the division chief of hematology-oncology and as an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

References

- Fellner C. Ipilimumab (Yervoy) prolongs survival in advanced melanoma: Serious side effects and a hefty price tag may limit its use. P T. 2012 Sep;37(9):503–530.

- Weber J. Review: Anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab: Case studies of clinical response and immune-related adverse events. Oncologist. 2007 Jul;12(7):864–872.

- Suarez-Almazor ME, Kim ST, Abdel-Wahab N, Diab A. Immune-related adverse events with the use of checkpoint inhibitors for immunotherapy of cancer. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Apr;69(4):687–699.

- Goldstein BL, Gedmintas L, Todd DJ. Drug-associated polymyalgia rheumatica/giant cell arteritis occurring in two patients after treatment with ipilimumab, an antagonist of CTLA-4. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Mar;66(3):768–769.

- Minor DR, Bunker SR, Doyle J. Lymphocytic vasculitis of the uterus in a patient with melanoma receiving ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Jul 10;31(20):e356.

- Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, et al. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2016 Nov 3;375(18):1749–1755.

- Yun S, Vincelette ND, Mansour I, et al. Late onset ipilimumab-induced pericarditis and pericardial effusion: A rare but life threatening complication. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2015;2015:794842.

- Heinzerling L, Ott PA, Hodi FS, et al. Cardiotoxicity associated with CTLA4 and PD1 blocking immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2016 Aug 16;4:50.

- Ludlow SP, Kay N. Delayed dermatologic hypersensitivity reaction secondary to ipilimumab. J Immunother. 2015 May;38(4):165–166.

- Horvat TZ, Adel NG, Dang TO, et al. Immune-related adverse events, need for systemic immunosuppression, and effects on survival and time to treatment failure in patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Oct 1;33(28):3193–3198.

- Heinzerling L, Goldinger SM. A review of serious adverse effects under treatment with checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Opin Oncol. 2017 Mar;29(2):136–144.

- Ipilimumab package insert.

- Friedman CF, Proverbs-Singh TA, Postow MA. Treatment of the immune-related adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors: A review. JAMA Oncol. 2016 Oct 1;2(10):1346–1353.

- Kumar V, Chaudhary N, Garg M, et al. Current diagnosis and management of immune related adverse events (irAEs) induced by immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2017 Feb 8;8:49.