Repeat labs were notable for white blood cell count of 8.84, hemoglobin 20.2, hematocrit 60, platelets 331. His creatinine was 2.1, albumin 2.4, bicarbonate 13.9, anion gap 26 and lactate 6.1. In the ICU, he was treated supportively, required two vasopressors and stress dose corticosteroids, and received 10 liters of crystalloid fluids, in addition to albumin boluses.

The patient had evidence of abdominal compartment syndrome, requiring an open abdomen after his laparotomy for several days before eventual closure. Also, he suffered from a small cardiac event with a troponin leak to 10.1. An echocardiogram was unremarkable (EF 51%).

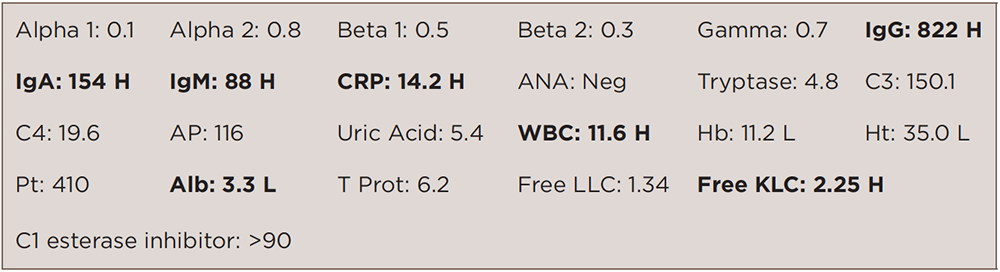

Other labs were notable for low IgG (379), IgM (43) and normal IgA (118). Serum electrophoresis was notable for low total protein, hypoalbuminemia (2.54), hypogammaglobulinemia (0.23) and no monoclonal band.

Within the next three days, the patient improved, his abdomen was closed, vasopressors were weaned, and he was extubated. The patient was discharged seven days after admission.

A month later, the patient was taken to the NIH and diagnosed with systemic capillary leak syndrome. In September 2014, he was placed on intravenous immunoglobulin indefinitely. (See Table 2)

The patient’s RA had stayed in remission since October 2013. He was taken off of leflunomide during his hospital course and placed on hydroxychloroquine from September 2014 to January 2015 for his RA. Hydroxychloroquine was discontinued in December 2014, because the patient developed a diffuse rash.

The patient was placed on adalimumab in September 2015 for flare of RA with manifestations of increased hand and foot pain, morning stiffness, four tender joints on 28-joint-count exam plus tender metatarsophalangeal joints.

As of February 2016, the patient’s RA and SCLS remained in remission, and the patient reported maintaining a very active lifestyle.

Discussion

We present a rare case of adult SCLS in a rheumatoid arthritis patient. The diagnosis of SCLS is clinical and may be difficult to recognize and diagnose on initial presentation. Hypotension, hemoconcentration, hypoalbuminemia and the absence of secondary causes of shock are typical. The singular combination of hypotension and elevated hematocrit reflects the profoundly reduced intravascular volume and endothelial barrier dysfunction unique to SCLS.4 The diagnostic evaluation should be performed concurrently with initial fluid management. Immediate intervention should be started because SCLS has a high fatality rate.5 Mortality ranges from 30% to 76%.6,7

The pathogenesis and pathophysiology of SCLS are relatively unknown. Reports suggest that VEGF and angiopoietin 2 (Ang2) contribute to endothelial contraction and may be associated with pathogenesis.8 Further investigations of various biomarkers, which may play an important role, are needed to clarify the pathophysiology of SCLS.5