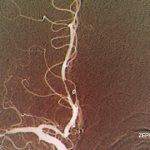

Figure 1: A head CT revealed a subacute infarct involving the right-posterior medial, parietal and occipital lobes.

Case report: A 60-year-old Hispanic male with poorly controlled hypertension was sent from the primary care clinic for evaluation of malignant hypertension with a systolic blood pressure above 200 mmHg. His symptoms at the time of presentation included episodic confusion, worsening vision and an unsteady gait.

A head computed tomography (CT) scan showed a subacute infarct involving the right posterior medial, parietal and occipital lobes (see Figure 1).

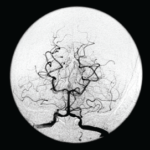

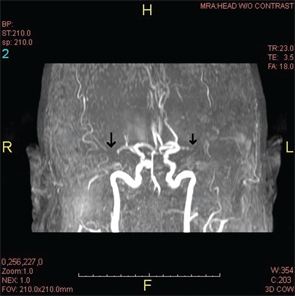

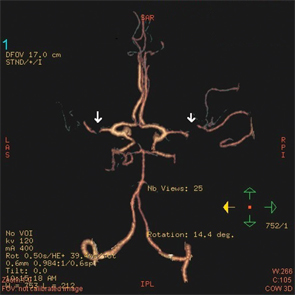

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) scan were performed. They demonstrated bilateral middle cerebral artery (MCA) stenosis with good collateral circulation and confirmed a subacute right occipito-parietal infarct, involving the splenium (see Figures 2A & 2B).

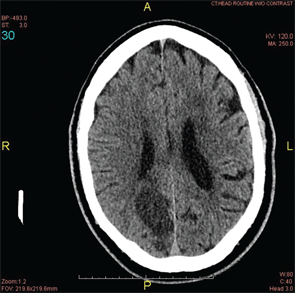

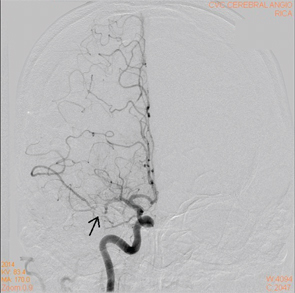

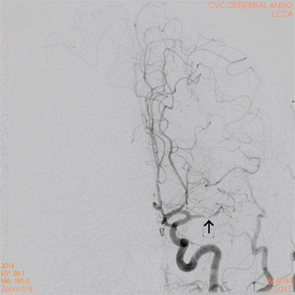

A CT cerebral angiogram was performed and showed near occlusion of the distal right middle cerebral artery, occlusion of the proximal left MCA and occlusion of the right posterior cerebral artery (see Figure 3).

The patient was started on aspirin, clopidogrel and atorvastatin. After a 14-day hospital course, the patient was discharged to home.

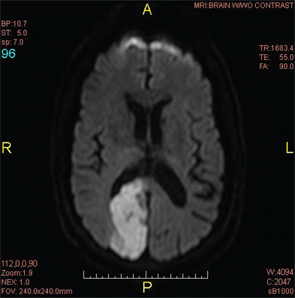

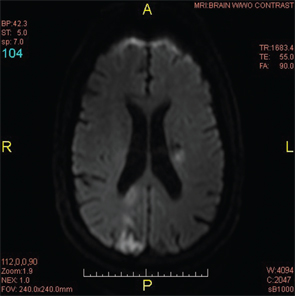

Two weeks later, the patient presented to the emergency department with a new-onset, right-sided facial droop and slurred speech. An MRI at this visit showed an acute lacunar infarct of the left corona radiata (see Figure 4). Despite normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and antinuclear antibody (ANA) tests, there was a concern for CNS vasculitis, and the patient was empirically started on high-dose steroids.

Further workup included the following studies: immunoglobulin levels, complement levels, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis for antibodies. All studies were negative. A repeat CT cerebral angiogram revealed long-segment stenosis of both MCAs (see Figures 5A & 5B). At this time, a diagnosis of moyamoya disease was made. The patient was started on warfarin (Coumadin) and discharged to home.

Figure 2A: An MRI of the brain confirmed a subacute infarct involving the right occipito-parietal lobe.

Figure 2B: An MRA revealed the lack of flow in the middle cerebral artery that could be attributed to an occlusion or stenosis.

Figure 3: A CT angiogram of the head revealed bilateral MCA stenoses and occlusion of the right posterior cerebral artery.

Discussion

Primary CNS vasculitis, also known as primary angiitis of the CNS (PACNS), and moyamoya disease are both rare causes of stroke and are often indistinguishable in clinical presentation. Although both may present similarly, physicians must learn to differentiate between them, because management for each differs greatly.

For moyamoya disease, no evidence suggests any benefit from corticosteroid therapy.

PACNS is a rare vasculitis that is limited to the brain and the spinal cord. It leads to diverse and non-specific neurological manifestations, with an increase in morbidity and mortality.1

Moyamoya, meaning a “hazy puff of smoke” in Japanese, is a chronic, occlusive cerebrovascular disease involving bilateral stenosis or occlusion of the terminal portion of the internal carotid arteries (ICA) and/or the proximal portions of the anterior cerebral arteries (ACA) and middle cerebral arteries (MCA) that leads to neurological deficits.

Epidemiology

CNS vasculitis was first seen and described from autopsy results in the 1950s and, at that time, was described as granulomatous angiitis. Recent estimates indicate that the annual incidence of PACNS is around 2.4 per million people. Although it has been reported in both children and adults, it is more commonly seen in men from 30–50 years old.1

Moyamoya disease was first described in Japanese literature in 1957 by Takaku and Suzuki.2 It is most commonly found in Asian populations. The incidence of moyamoya disease is highest in Japan with approximately three cases per 100,000 persons, which is 30–40 times higher than in the U.S., where the incidence is approximately 0.086 cases per 100,000 persons. Unlike in PACNS, moyamoya disease is more common in females, with the peak ages of incidence in children at 5 years old and adults in their 40s.3

Clinical Presentation

Figure 4: A repeat MRI of the brain two weeks after the initial MRI revealed a new lacunar infarct of the left corona radiata and the old infarct in the right posterior occipito-parietal lobe.

PACNS often has a long prodromal period and is thought to rarely present with acute manifestations. In a review of 116 patients, 83% presented with a change in mental status, 56% with headaches, 30% with seizures, 14% with stroke and 12% with cerebral hemorrhage.4

Clinical presentation of moyamoya disease differs between adults and children. Adults typically present with transient or permanent cerebral infarction and intracranial hemorrhage; however, children present mainly with ischemic events. Although patients can present without any symptoms, patients more often will present with visual deficits, speech disturbances, headaches, intellectual deterioration, cranial nerve palsies and/or gait disturbances.3

Diagnosis

In PACNS, 80–90% of patients have abnormal CSF findings characterized by elevated total protein concentrations.7 Inflammatory markers, such as ESR and CRP, are typically normal, as are ANCA and ANA.

Although imaging of the head is usually nonspecific, the most common findings are infarcts. The infarcts can involve any part of the subcortical white matter, deep gray matter, deep white matter or the cerebral cortex. Angiography is often used as a diagnostic test, although its specificity and sensitivity are very low and, therefore, cannot be used as a sole determinant of the etiology of the patient’s symptoms. Typical findings, however, include alternating areas of narrowing and dilation of the arteries, which can give the vessels a beaded appearance. Other diagnostic features include arterial occlusion of many cerebral arteries without atherosclerosis or other abnormalities, but in the end, the gold standard for diagnosis of PACNS continues to be a brain biopsy. Histopathology will often show either a granulomatous, lymphocytic or necrotizing vasculitis.3

Figure 5A: A cerebral angiogram showing right MCA stenosis.

Compared with PACNS, CSF analysis is usually unremarkable in patients with moyamoya disease; however, unlike PACNS, diagnosis of moyamoya is typically made on the basis of radiological findings.7 To diagnose moyamoya disease, the following MRI–MRA criteria need to be met:5,6

- Stenosis or occlusion of the terminal part of the ICA and/or the proximal portion of the ACA and/or MCA;

- Visualization of an abnormal arterial vascular network around the stenotic and/or occluded lesions; and

- Symmetry of the lesions, showing bilateral involvement.

Therefore, conventional digital subtraction angiography remains the gold standard for diagnosing moyamoya disease.7

Because of moyamoya disease’s ability to mimic central nervous system vasculitis, it is important for rheumatologists to recognize this condition & diagnose it appropriately.

Treatment

Because PACNS is a very rare disease, no good randomized control trials comparing one treatment modality with another exist. The most commonly accepted treatment typically consists of glucocorticoids, possibly with cyclophosphomide.1

For moyamoya disease, no evidence suggests any benefit from corticosteroid therapy. Surgical revascularization for patients with ischemic moyamoya disease has been shown to decrease the frequency of transient ischemic attacks and risk of cerebral infarction.

Figure 5B: A cerebral angiogram showing left MCA stenosis.

On the other hand, for patients who cannot undergo surgical intervention, either due to recent infarction or good spontaneous revascularization, medical therapy with a cerebroprotective agent, edaravone, and an antithrombotic agent, such as aspirin, ozagrel, argatroban or heparin, is recommended. For hemorrhagic moyamoya disease, ventricular drainage and hematoma evacuation are the treatment modalities of choice.6

Conclusion

On initial presentation, both PACNS and moyamoya disease present similarly. Because treatment differs significantly, it’s important to differentiate between the two disorders. Given that both disorders can lead to permanent, serious, neurologic damage, it’s crucial that an accurate diagnosis be made so the correct treatment can be initiated as soon as possible.

Unlike PACNS, diagnosis of moyamoya is typically made on the basis of radiological findings.

Hopefully, by continuing to learn of these new cases, physicians will be better equipped to diagnose and treat these disorders appropriately and, thus, improve patient outcomes.

Dr. Kim

Joey Kim, MD, is an internal medicine resident currently finishing his third year of residency at Stony Brook University Hospital in New York. He hopes to pursue a career in rheumatology in the future.

Megha Patel-Banker, MD, is a board-certified rheumatologist who completed her fellowship training at Stony Brook University Hospital and currently practices in the Dallas area.

Matthew Abramson, MD, is a second-year internal medicine resident at Stony Brook University Hospital and has a keen interest in rheumatology.

Mehwish Bilal, MD, is a practicing rheumatologist in St. Louis who completed her fellowship training at Stony Brook University Hospital.

Sanjay Godhwani, MD, is a practicing rheumatologist in Long Island and completed his fellowship training at Stony Brook University Hospital.

Asha Patnaik, MD, is a board-certified rheumatologist currently practicing as an assistant professor at Stony Brook University Hospital, where she completed her fellowship training.

Heidi Roppelt, MD, is a board-certified rheumatologist who completed her fellowship training at Stony Brook University Hospital. She is currently associate professor of medicine at Stony Brook University Medical Center and practices rheumatology at Southampton Hospital in Long Island.

Qingping Yao, MD, PhD, is a board-certified rheumatologist and professor of medicine, chief, Division of Rheumatology, Allergy & Immunology, Stony Brook University.

References

- Alba MA, Espígol-Frigolé G, Prieto-González S, et al. Central nervous system vasculitis: Still more questions than answers. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011 Sep;9(3):437–448.

- Suzuki J, Takaku A. Cerebrovascular ‘moyamoya’ disease. Disease showing abnormal net-like vessels in base of brain. Arch Neurol. 1969 Mar;20(3):288–299.

- Smith ER, Scott RM. Moyamoya: Epidemiology, presentation, and diagnosis. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2010 Jul;21(3):543–551.

- Calabrese LH, Duna GF, Lie JT. Vasculitis in the central nervous system. Arthritis Rheum. 1997 Jul;40(7):1189–1201.

- Janda PH, Bellew JG, Veerappan V. Moyamoya disease: Case report and literature review. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2009 Oct;109(10):547–553.

- Research Committee on the Pathology and Treatment of Spontaneous Occlusion of the Circle of Willis, Health Labour Sciences Research Grant for Research on Measures for Infractable Diseases. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of moyamoya disease (spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis). Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2012;52(5):245–266.

- Kraemer M, Berlit P. Primary central nervous system vasculitis and moyamoya disease: Similarities and differences. J Neurol. 2010 May;257(5):816–819.