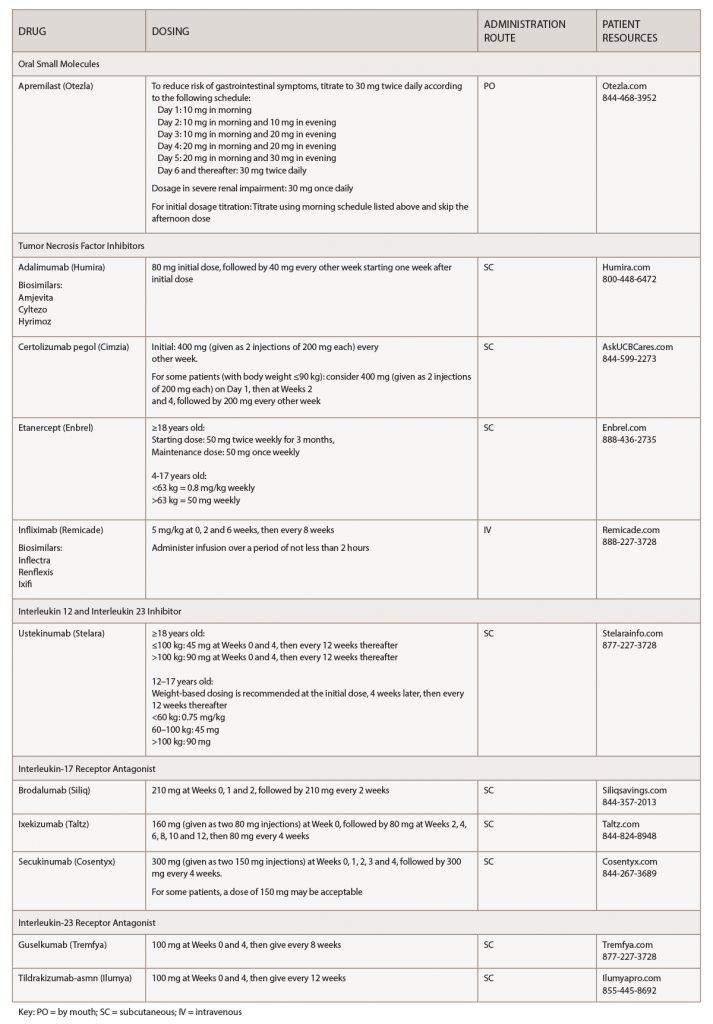

Over the past few years, biosimilars and other new drugs have been introduced to treat rheumatic illnesses. Some of the conditions we treat have numerous drug option; others have few or only off-label options. This series, “Rheumatology Drugs at a Glance,” provides streamlined information on the administration of biologic, biosimilar and other medications used to treat patients with rheumatic disease. In Part 2, we discuss the 17 available options to treat psoriasis (see Table 1).

Psoriasis vulgaris (the medical name for the most common form of psoriasis) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that manifests characteristic plaques on the skin: well-demarcated, red plaques with silvery scales that can appear on any area of the skin, although the scalp, elbows, knees and trunk are the most common locations. Although skin involvement is often the most prominent and widely recognized manifestation of this disease, recognition of the condition as a chronic, multisystem inflammatory disorder is imperative to optimize management.1 Psoriasis follows a relapsing course and can change unpredictably over time in individual patients, which can have a significant effect on their quality of life. Addressing both physical and psychosocial aspects of psoriasis is necessary for optimal disease management.

The majority of patients with mild to moderate psoriasis can manage their disease with topical medications or phototherapy. However, patients with moderate to severe disease require treatment with biologic agents, either as monotherapy or combined with other topical or systemic medications.

An autoimmune disease, psoriasis primarily affects the skin, but is associated with the inflammatory arthritis, psoriatic arthritis (PsA). PsA has a prevalence of 25–30% in patients with psoriasis.2

(click for larger image) Table 1: Psoriasis Medications at a Glance

Note: These medications should be used for adults 18 years old or older, unless otherwise specified.

Skin conditions carry a stigma, and psoriasis is associated with a major psychological burden.3 Adherence to biologics is a major barrier for patients, and biologic use is associated with high discontinuation rates.4 When treating patients with psoriasis, it’s important to explain the natural history of the disease, and also to advise patients that this is a chronic disease that can be controlled with therapy, but that remission does not equal cure.

Educating patients and improving communication will optimize the patient-provider relationship through shared decision making. It’s important to select the best therapeutic option for, and with, the patient to improve adherence. This will positively impact patient satisfaction.

Biologic therapies for psoriasis offer patients improved quality of life over traditional systemic therapy with regard to improved efficacy and less toxicity.5 Providers should be aware of the major risks when using biologics for the treatment of psoriasis: infection and nonmelanoma skin cancer. Appropriate counseling and screening are necessary to attenuate the risk.

All biologic prescriptions include an FDA-approved medication guide for patient instruction. Patients should be encouraged to read this before starting a biologic and after each refill.

Treatments for psoriasis can be expensive, and healthcare providers can help make treatment costs more manageable for patients. A number of financial assistance resources are available to patients, and patients can also contact the manufacturers to request copay assistance. Your staff can explore patient assistance programs for those who don’t have insurance.6

Depending on a patient’s coverage and the medication(s) they use, a specialty pharmacy may dispense the drugs. Most specialty pharmacies have clinical pharmacists available to help patients manage insurance issues; monitor for adverse effects, effectiveness and adherence issues; and serve as a drug information resource.