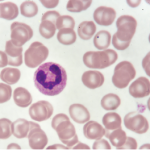

Image Credit: Gary Carlson/ScienceSource.com

Activated neutrophils.

SAN FRANCISCO—To unravel the mysteries of how autoimmunity begins in the body and, one day, to interrupt that process, rheumatology researchers are exploring the role of neutrophils, especially when they form and release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).

At a panel discussion on Nov. 6, 2015, held at the American College of Rheumatology’s Basic Research Conference, the precursor to the 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, three speakers explored the emerging importance of studying the role of NETs in autoimmunity in such diseases as systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis, rheumatoid arthritis and gout.

Neutrophils are a first-line defense system against infectious agents. When they release chromatin and granular proteins to form NETs, they can trap and destroy pathogens as a last line of defense against disease. However, neutrophils and NETs may also play a role in the induction of the autoimmune response, a connection that is not yet fully understood, the panelists said.

Neutrophils and their cell death, called NETosis, play a role in lupus pathogenesis, said Mariana J. Kaplan, MD, chief of the Systemic Autoimmunity Branch at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) in Bethesda, Md.

Low-density granulocytes (LDGs), a subset of neutrophils, are present in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells in samples from lupus patients. “Neutrophils are the main source of type-1 interferon in lupus bone marrow,” she said. “They are prematurely released from marrow due to some stimuli, although we don’t yet know what.”

LDGs express high levels of the antigen CD-15, have a great ability to synthesize type-1 interferon, and are thought to play a role in SLE pathogenesis and organ damage, she said.

“We hypothesize that LDGs may play important pathogenic roles in lupus due to their enhanced pro-inflammatory phenotype, increased capacity to form NETs and damage the endothelium,” Dr. Kaplan said in a follow-up interview.

Although most lupus patients show an enhanced ability to form NETs, about one-third have an impaired ability to clear NETs from their blood. “This imbalance may promote enhanced exposure of modified auto-antigens that could promote autoimmune responses,” she said. NETs amplify type-1 interferon responses and activate complement in these patients, she said. NETs are also a strong activator of macrophages and can exacerbate inflammatory responses in the periphery or affected organs.

Lupus LDG NETs are enriched in oxidized, interferogenic, mitochondrial DNA, Dr. Kaplan said. “Not all NETs are created equal. NETs are quite toxic to vasculature, or vasculopathic. They’re good at killing endothelial cells, and they’re potent inducers of thrombosis.” NETs also oxidize lipoproteins and are proatherogenic, and so may play a role in cardiovascular disease risk for these patients.

One potential target to try to reduce NET formation and subsequently protect lupus patients from that vascular damage is to inhibit peptidylarginine deiminases (PADs), Dr. Kaplan said. In murine models, mice that received PAD inhibitors had improved endothelial function, significant decreases in renal inflammation and proteinuria, and protection against the severity of skin diseases. PAD inhibition also abrogated prothrombosis in these mice.

Understanding the roles of neutrophils and NETs in autoimmunity is an important step in developing future therapies for rheumatic diseases, she said.

“As with any biologic process, there is evidence that NETs can have both immunostimulatory and tolerogenic roles in inflammation. This may be disease and context dependent, and it will be important to better understand these functions to design the best therapeutic targets for specific diseases,” she said.

NETs & ACPAs

Alternate forms of neutrophil cell death exist, said Marko Radic, PhD, associate professor of Microbiology, Immunology, and Biochemistry at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis. These include apoptosis and NETosis. Dr. Radic spoke on the relationship between NETs and anti-citrullinated protein antigens (ACPAs), which play a key role in RA inflammation.

In an infection, neutrophils release chromatin in NETs, which trap microbes. “Chromatin can act as a sort of flypaper to which bacteria can attach” in NETs, he said. In inflammation, NETosis may be a mechanism for DNA and chromatin to escape from the cell, and this type of cell death is an area of interest for exploring the triggers of autoimmunity in RA.

“At this point, there is little doubt that understanding what differentiates appropriate versus excessive NETosis holds the key to understanding initial stages in the pathogenesis of RA,” said Dr. Radic in a follow-up interview. “Neutrophils from a number of inflammatory conditions such as RA or lupus are generally more prone to undergo NETosis. In addition, a number of conditions that predispose one to RA, such as smoking, obesity, or certain infections, induce increased levels of NETosis. In turn, NETosis is usually accompanied by the activation of the PAD4 enzyme, which is responsible for citrullinating intra- and extracellular substrates.”

Citrullination of histones may have something to do with disease activity, and two key questions are whether or not citrullinated histones are autoantigens and how PAD4 is regulated, he said. The answers to questions like these may help us better understand RA pathogenesis, because increased levels of ACPAs, the antibodies to those citrullinated proteins, are seen months or years before clinically apparent RA.

One physiological stimulator of NETosis may be neutrophil swarming, and this process is intriguing to researchers as well, said Dr. Radic. “Neutrophil swarming is the coordinated gathering of neutrophils. This migration can be induced by infectious pathogens, like toxoplasma, and localized cell death may occur due to trauma or physical injury” that could be the early trigger of inflammation in rheumatic disease, he said. “The signals that induce swarming and the receptors on the neutrophils that allow them to respond are an active area of research. In part, this neutrophil migration is thought to form the basis for subsequent events in inflammation.”

NETosis provides an amplification step in the inflammatory process and promotes pro-inflammatory gene expression, said Dr. Radic. It allows the release of the neutrophils’ granule contents and chromatin.

“There seems to be a mutual relation between NETosis and neutrophil swarming in that neutrophils that undergo NETosis attract even more swarming neutrophils to the site,” said Dr. Radic. “Conversely, swarming seems to predispose cells toward NETosis. So, mutually, these events seem to foment each other.”

Resolving Role

Neutrophils also have strategic and tactical functions, said Martin Herrmann, PhD, scientific group leader, Autoimmunity Research and Cellular Immunology, at Friedrich-Alexander University in Erlangen, Germany.

NETs play a key role in the induction of gout, and “the resolution phase of inflammation in gout is as important as the induction phase,” he said. If inflammation is not controlled after an infection or injury, it becomes problematic. NETs contribute to the resolution of MSU crystal-induced inflammation in gout. Dr. Herrmann described a vicious circle of activity: neutrophil recruitment, NETosis, and IL-8 release. NETs’ role in gouty inflammation induction and resolution may yield more clues in understanding autoimmunity in general, he said.

In the early phase of this type of gout, MSU crystals induce the formation of NETs and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. “At high neutrophil densities, NETs tend to aggregate. It looks like this is an amorphous material which forms the basis of tophi,” he said. But the cytokine and chemokine release by the aggregated NETs is strongly reduced. The aggregated NETs sequester and degrade these pro-inflammatory mediators. In MSU crystal-induced gout studies in vivo, aggregated NET formation depends on ROS production, he added.

Oxidative burst is required to prevent MSU-induced bone destruction and resolve MSU-induced inflammation, Dr. Herrmann added. Neutrophils and their activity are required for the resolution of inflammation in gout, and he described studies where neutrophils were depleted from mice with paw edema, causing their inflammation and swelling to become chronic.1

In follow-up questions from the audience, Dr. Herrmann explained that colchicine, a traditional gout therapy, delays NETosis, although how this happens is difficult to explain.

Susan Bernstein is a freelance medical journalist based in Atlanta.

Reference

- Schauer C, Janko C, Munoz LE, et al. Aggregated neutrophil extracellular traps limit inflammation by degrading cytokines and chemokines. Nat Med. 2014 Apr 28(5);20:511–517.