Why do patients hurt more in the morning than in the evening? Why do rheumatologists ask about morning stiffness and not evening stiffness? Why is it important in clinical trials to assess the effects of therapy at the same time point during the day?

The answers to all of these questions relate to the circadian rhythm. The term circadian rhythm refers to the 24-hour cycles in the physiological processes of living organisms that include, among others, the cycle of hormone levels or nerve activity. While circadian rhythms are a fundamental feature of the biology of animals, they are usually not considered as important determinants of disease, although their influence is profound.

In this article, we will address two issues: Why is the circadian rhythm relevant for the clinical practice in rheumatology? and How can the circadian rhythm influence the symptoms of my patient?

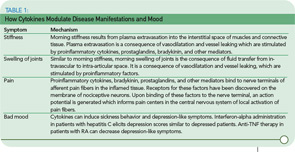

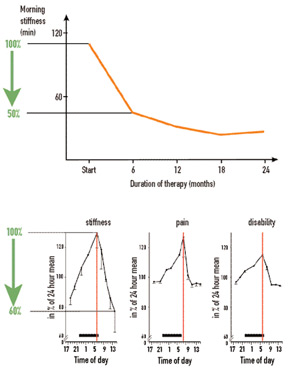

In considering symptoms of RA, it is remarkable that the improvement of morning stiffness induced by prednisolone after six months is similar in magnitude to the improvement of morning stiffness during a single day (see Figure 1, p. 15). Under both conditions—the clinical trial and the course of one day—an improvement of 40% to 50% can occur. Imagine, therefore, a situation in which an investigator in a clinical trial did not pay attention to the time point of examination and recorded improvement that reflected the diurnal variation as much as a sustained treatment effect.

Because patient symptoms can vary during the course of a day in clinical trials, assessment of symptoms can also vary depending on the time point of the visit. Patients often feel better later in the day. Should one therefore recommend an afternoon visit for the patient because the symptoms are less severe then? Indeed, many patients would prefer an afternoon visit because it is much easier for them to get up and around and travel to the clinic. Because symptomatology can have a pronounced diurnal cycle with a maximum in the morning, the underlying causal mechanisms are relevant for pathophysiology of rheumatic diseases, for clinical patient care, and for optimizing treatment strategies.

The Discovery of Circadian Rhythms

In the early 1970s, studies using brain-lesion techniques as well as metabolic and electrophysiological experiments indicated that, in mammals, there is a key structure in the brain which governs biological rhythms.1 As these studies showed, this central circadian oscillator is located in the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) (see Figure 2, p. 16). The oscillator induces 24-hour cyclic changes of membrane potentials of neurons of the SCN.

In the following years, links between the SCN and many centers in brain were discovered. Among others, the endocrine and sympathetic nervous centers are controlled by the SCN. Because the circadian rhythm is generated in the SCN of the hypothalamus, observations can provide new clues to understand neuroendocrine immune pathways relevant to rheumatic diseases. Because these aspects have been best elaborated in RA, the findings in this disease are discussed here. The mechanisms responsible for oscillation in suprachiasmatic neurons will not be considered but are reviewed elsewhere.2

Circadian Rhythms of Serum Cytokine and Hormone Production

Because of the favorable effects of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–α and anti–interleukin (IL)-6 therapy in large clinical trials, rheumatologists recognized the central role of these proinflammatory cytokines in rheumatic diseases. These cytokines are also important in symptoms such as stiffness, joint swelling, pain, and mood (see Table 1, p. 15). An important question, therefore, is whether cytokines demonstrate a circadian oscillation. Indeed, both IL-6 and TNF-α display a circadian rhythm, with maximum levels in the early morning hours (see Figure 3, p. 16).2 In healthy subjects, the peak value of IL-6 is found at about 6 a.m. In patients with RA, the peak value of IL-6 appears at 7 a.m. Thus, a morning time shift of the peak value occurs with inflammatory disease. In healthy subjects, IL-6 serum levels are approximately 2–4 pg/ml whereas in patients with RA these levels are 20–40 pg/ml.