Be clean in person, well dressed, and anointed with sweet smelling unguents.

—Hippocrates

A few months ago, I decided to clean out my office. For over 20 years, I had successfully avoided this grim task, but now our hospital was going to cover the cost of converting our glum, cinderblock-design workspaces full of mismatched furniture and stained carpets to something more modern and tasteful. Out with the old and in with the new.

Clearing through a pile of old letters accumulating dust in my rusting filing cabinet, I came across one that was sent to me about 25 years earlier by a former secretary who worked in our division. She told me that she had felt uncomfortable typing this letter of recommendation written on my behalf and wanted me to read its contents. Since it came in a sealed envelope, I decided not to open it, but threw it into the bottom drawer and forgot about it until now. The first half of the letter was complimentary about my work ethic and talents, but the last paragraph concluded on a somewhat dour note. The author, Dr. Y, railed at my attire, suggesting that my clothing often exceeded “the sartorial norm of our hospital.”

What was he talking about? For the five years that I worked as a research fellow in a lab, my work attire consisted of a pile of clean shirts, a few pairs of faded corduroys, and a single dark blue tie, all stuffed into my work locker. This setup allowed me to run to work each day, shower, and have a fresh change of clothing waiting for me. Actually, the only day of the week when what I wore really mattered was Thursday, my clinic day. The arrangement worked exceedingly well except for one unfortunate Thursday, when I inexplicably ran out of pants and presented to clinic sporting a shirt, tie, and sweat pants. I imagine that my sartorial score plummeted that day. Fortunately, there are no online videos that recorded this fashion show for posterity.

What Doctors Wore: The Early Years

After moving from Montreal to Boston, I became acutely aware of the clothing differences between these two cities. In Montreal, the French flair dominated clothing choices. Though house officers donned the standard hospital whites, many of our attending physicians were literally dressed to kill. Natty suits and blazers for both men and women and fashionable footwear were de rigueur. Think of the standard attire of a chic Parisian and you will get the picture.

Boston, on the other hand, lived up to its puritanical heritage. There seemed to be no change in clothing styles with the passing of each season. Faded khakis and checkered shirts were the year-round staple, and in the hospitals, there was the ubiquitous white coat. I noticed that there were two styles, the short white jacket and the long, full-length coat. I was accustomed to identifying the rank of strangers in the hallways based on the length of this item. I assumed that faculty members and some fellows wore full-length coats while students and residents preferred short jackets. But in Boston, this assumption did not hold true. Many faculty members preferred wearing the short white coat. This observation puzzled me. Alas, I discovered that in Boston, physicians who trained at that “great hospital built on the marshes of Back Bay” often wore the short coat as a way of signaling to others their common training heritage. This must be the apparel equivalent of a secret society handshake.

Whether short or long, the white coat has symbolized the integrity and professionalism of our craft.1 Surprisingly, the adoption of the white coat by the medical profession is a fairly recent development. During the Middle Ages, doctors in Europe preferred wearing long dark robes with pointed hoods, leather gloves, boots, and the most bizarre masks featuring long beaks, which were filled with lavender or bergamot oil. Amulets of dried blood and ground-up toads were worn at their waists. They doused themselves with vinegar and chewed the bitter angelica root before approaching a victim, all in an effort to protect themselves against the bad odors that were considered to be the vectors of disease.2 Eventually, these nightmarish outfits were replaced by a more stylish and less frightening choice, namely, black clothing. This preference made sense, since medical encounters were considered to be serious and formal matters. During this era, virtually all of medicine entailed many worthless cures and much quackery. Most encounters with a physician rarely benefited the patient, and frequently were a precursor to death. Thus, patients seeking medical advice did so only as a decision of last resort. Doctors may have chosen to wear black as a way of emulating the attire of the other professions that dealt with death—the clergy and undertakers. Talk about color-coding the subject of death!

From Black To White

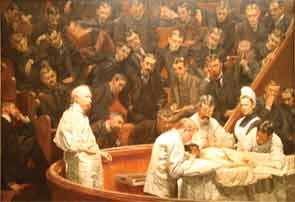

The transition from black to white took place during the latter half of the 19th century. Evidence of this change can be observed by comparing two historic paintings. Thomas Eakins was a renowned realist painter, known for his exacting work. In 1875, he created what is arguably one of America’s greatest paintings, entitled “The Gross Clinic” (see Figure 1).3 It depicts a scene from Jefferson Medical College’s amphitheater in Philadelphia, showing Dr. Samuel Gross and his assistants, all dressed in black formal attire, performing an operation on the leg of a young man. Though the concepts of Joseph Lister were slowly gaining popularity in European medical circles during this era, there was still a high degree of naiveté regarding antisepsis. Apparently, Lister would perform operations wearing his black suits.

Over the next few decades, a better understanding of sepsis began to dramatically transform physicians from being purveyors of home remedies and quackery to more thoughtful practitioners. Clinicians began to better understand how to prevent bacterial contamination. This progression was highlighted in Eakins’ largest work, the operating theater masterpiece, entitled “The Agnew Clinic” (see Figure 2). This painting was commissioned for $750 in 1889 by three undergraduate classes at the University of Pennsylvania to honor their teacher, Dr. D. Hayes Agnew. In it, he is seen wearing a white smock performing a mastectomy. His assistants are also wearing white, suggesting that a new sense of cleanliness pervaded the environment. The patient is swathed in white sheets and the nurse is wearing a white cap. Finally, medicine was beginning to emerge out of the depths of darkness.

The White Coat: A Symbol of Credibility

Over the past hundred years, the white coat has served as the physicians’ symbol of recognition, professionalism, and trust. It identifies the wearer as being competent and trustworthy. This is especially important at the time of a new patient encounter, when several undercurrents are at play.4 The patient and doctor not only exchange medical information, but also assess each other to determine whether a strong therapeutic relationship can be built. What is the doctor’s appearance? What is his or her demeanor? Wearing a white coat helps.

Numerous studies have confirmed that patients have the most confidence in doctors who wear one. For example, patients surveyed in a recent study at one outpatient clinic overwhelmingly preferred doctors photographed in formal attire with a white coat.5 The patients also said they were more likely to divulge their social, sexual, and psychological worries to the clinicians in the white coats than to the other doctors. Similarly, a survey of patient and family-member preferences in an intensive care unit setting observed that a white coat was preferred over doctors wearing surgical scrubs or business suits by a 2:1 ratio and a fourfold margin, respectively.6

The white coat has morphed into a symbol of medical integrity. The Arnold P. Gold Foundation of New York City, whose mission is to perpetuate the tradition of the caring doctor by emphasizing the importance of the relationship between the practitioner and the patient, has actively promoted the White Coat Ceremony to welcome entering medical students and help them establish a psychological contract for the practice of medicine. The event emphasizes the importance of compassionate care for the patient as well as scientific proficiency. White-coat ceremonies have gained popularity worldwide, adding to the prestige of this garment.

Enclothed Cognition: Can Your Clothes Make You Smarter?

How did the white coat achieve this preeminent status in medicine? Perhaps the answer lies deep within our psyche. It seems that we think not just with our brains but with our bodies, too. According to theories of embodied cognition, our thought processes are based on physical experiences that set off associated abstract concepts. This idea has been carried a few steps further by Adam Galinsky, PhD, professor of management at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill.7 Galinsky and colleagues introduced the term “enclothed cognition” to describe the systematic influence that clothes have on the wearer’s psychological processes. They proposed that enclothed cognition involves the co-occurrence of two independent factors—the symbolic meaning of the clothes and the physical experience of wearing them.

First, they explored the effects of wearing a lab coat in a group of nonmedical volunteers. A pretest found that a lab coat was generally associated with heightened attentiveness and carefulness. Thus, the researchers predicted that wearing a lab coat would increase performance on attention-related tasks. In the first experiment, physically wearing a lab coat increased selective attention compared to not wearing a lab coat. In two subsequent experiments, wearing a lab coat described as a doctor’s coat increased sustained attention compared to wearing a lab coat described as a painter’s coat, and compared to simply seeing or even identifying with a lab coat described as a doctor’s coat. Thus, their research suggested that the symbolic meaning and the physical experience of wearing certain attire such as a white coat may influence the wearer’s cognitive skills.

Despite these benefits, some physicians and ethicists have argued that the white coat can actually interfere with the doctor–patient relationship. They suggest that it has evolved into a symbol of authority that establishes a hierarchic relationship, which may impede better communication. Indeed, wearing a white coat sometimes serves as a power trip. This is especially true when doctors and other medical personnel are sporting lab coats, wearing surgical scrubs or dangling stethoscopes around their necks when they are out shopping in a supermarket.

What might we conclude from all of this? What doctors wear or are perceived to wear can affect how patients relate to them. For example, one study of emergency room visits focused on the impact of male doctors wearing a necktie.8 When discharged patients were surveyed, approximately 40% incorrectly recalled whether their doctor was wearing a tie. More fascinating was the observation that patient satisfaction responses actually correlated with the mere impression of the presence of a tie, independent of objective reality.

It would be wrong to conclude that as physicians, we are what we wear. The white coat or the necktie won’t really make you a smarter doctor or a more astute clinician, despite what the behavioral economists suggest. Haven’t we all met buffoons wearing bowties? (Though I still love mine!) In fact, in the United Kingdom, the National Health Services advises doctors to shed their white coats, jackets, and ties because of the propensity for clothing to become vectors for transmission of infection. Though this admonition has not yet reached our shores, it may be time for doctors to reflect on their clothing choices.

A thoughtful opinion piece written by a neurology resident at my hospital describes his own views on the subject:

“I have had the good fortune to encounter a wide and rich spectrum of opinions from patients, friends, and colleagues on the matter of proper physician attire, perhaps encouraged by my absent white coat, absent necktie, shaved head, bilateral black hoop earrings, and tattoos covering approximately 17% of my skin (according to the Lund–Browder burn chart). With only one exception (a mildly demented elderly man in heart failure), every one of the uncommon suggestions to upgrade my appearance for the sake of patient care has come from a physician colleague. In contrast, there have been countless moments of connection with patients who confided that some aspect of my appearance made them feel more comfortable.”9

I wonder what Dr. Y would think about this resident’s appearance. Fortunately for all concerned, Dr. Y has retired.

Regardless of the chosen apparel, there is little doubt that what really matters is not the clothing, but the person. Care, compassion, and concern are the attributes that all patients seek from their caregivers. A smile and some genuine warmth go a long way toward reassuring the patient. Although you can probably get away wearing just about any clean outfit, I wouldn’t recommend those worn by the plague doctors. Unless you are playing doctor at a Halloween party.

Dr. Helfgott is physician editor of The Rheumatologist and associate professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology, immunology, and allergy at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

References

- Gherardi G, Cameron J, West A, Crossley M. Are we dressed to impress? A descriptive survey assessing patients’ preference of doctors’ attire in the hospital setting. Clin Med. 2009;9:519-524.

- Townsend, GL. The plague doctor. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1965;20:276-277.

- Hochberg MS. The doctor’s white coat—An historical perspective. Virtual Mentor. 2007;9:310-314.

- Chung H, Lee H, Chang DS, et al. Doctor’s attire influences perceived empathy in the patient–doctor relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89:387-391.

- Rehman SU, Nietert PJ, Cope DW, et al. What to wear today? Effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. Am J Med. 20051;18:1279-1286.

- Au S, Khandwala F, Stelfox HT. Physician attire in the intensive care unit and patient family perceptions of physician professional characteristics. JAMA Internal Med. 2013;173:467-468.

- Adam H, Galinsky AD. Enclothed cognition. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2012;48:918-925.

- Pronchik DJ, Sexton JD, Melanson SW, et al. Does wearing a necktie influence patient perceptions of emergency department care? J Emerg Med. 1998;16:541-543.

- Bianchi MT. Desiderata or dogma: What the evidence reveals about physician attire. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:641-643.