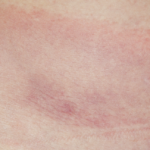

“The clinical picture is very characteristic. The illness begins with one (and always only one) fairly small round blotch. This spreads outward so that the outer periphery forms a small 1 to 2 cm wide ring. This ring gradually widens, while the center fades little by little until it assumes a wholly natural skin color, sometimes with a mild cyanotic tone. The wider the ring extends peripherally, the paler and less distinct it becomes until at last, after several weeks or at most after a few months, it disappears entirely.”

Not everyone was impressed. A French dermatologist, Dr. Jacques Strandberg, described the case of a woman who developed a similar lesion that began on her upper arm. Five months later, it had extended “across the breast and could only with difficulty be hidden by the application of powder when the patient wore a decollete dress.”4 Nonetheless, he concluded that, “the disease is of no importance for its own sake and is rather to be looked on as a freak.” Perhaps Dr. Strandberg was too focused on fashion rather than biology! In contrast, Dr. Afzelius was not sure about the etiology of the rash, but speculated that it was “introduced by the bite of a tick (Ixodes reduvius) or another insect.”3 This concept lay dormant for the next half century.

Fast-forward to the summer of 1977. Dr. Steere, armed with the knowledge that residents of a wooded area were developing bull’s-eye rashes and arthritis, telephoned Willy Burgdorfer MD, PhD, a specialist in the field of tickborne diseases at the Rocky Mountain National Laboratories in Hamilton, Mont., to inquire about how to evaluate ticks for secondarily acquired microorganisms. After all, ticks were known as vectors for a host of illnesses ranging from babesiosis to Q fever to Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Over the next few years, Dr. Burgdorfer collaborated with Dr. Steere and others in an effort to identify the microorganism that might be the causative agent of this newly described illness, Lyme disease. First, he attempted to recover rickettsiae from the eastern deer tick, Ixodes dammini, (named after its discoverer, a pathologist at my hospital, Gustave Dammin, MD) garnered from Shelter Island, N.Y., a well-known endemic locus of Lyme arthritis. Yet, when he examined Giemsa-stained smears taken from the midgut diverticula of two such ticks, he did not find the expected rickettsial microorganisms, but instead discovered the presence of, “rather long, irregularly coiled spirochetes.”5 Indirect immunofluorescence studies revealed that antibodies extracted from the serum of Lyme disease–infected patients reacted positively with the spirochete, while serum from control patients did not, thereby confirming the relationship between the tick-derived spirochete and Lyme disease. The final link to Dr. Afzelius’ bull’s-eye lesion had been formed. Keeping with tradition, the organism was named Borrelia burgdorferi.