What Drives The Placebo Effect?

The placebo effect is a fundamental part of the healing process. In fact, this effect is considered by some authors to be hardwired in our brains, since it may offer an evolutionary advantage to the host by providing a critical pathway for promoting optimal health.5 It has been observed more commonly in the field of psychiatry, where some consider psychotherapy to be the ultimate placebo therapy. In Parkinson’s disease, the placebo effect has been shown to improve symptoms by enhancing dopamine release in the basal ganglia.6 It has been found to modulate the response to pain by increasing brain endorphin and endogenous opioid production, similar to what has been observed in the “runner’s high.” In a fascinating study of rectal pain, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) observed that the expectation of pain relief could substantially change the perceived degree of pain of visceral stimuli. This effect was modulated through activation of pathways in the prefrontal and somatosensory cortex and the thalamus.6 These studies seem to delineate the biological basis for the observation by the late astronomer Carl Sagan, who elegantly stated that “hope can be transformed into biochemistry.”7

We must remember that our words, attitudes, and behaviors play dominant roles in both the doctor–patient interaction and in the placebo response. Yes, we can be honest and compassionate at the same time.

Nocebo: Placebo’s Evil Twin

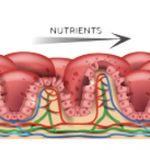

Negative expectations deriving from the clinical encounter can produce negative outcomes. This was apparent during my encounters with Mimi. Though she never took any of the drugs that I recommended, I suspect that none would have been tolerated. We have learned that in placebo-controlled clinical trials, patients receiving a placebo therapy often reported side effects that were similar to those experienced by patients receiving the study treatment. In fact, this phenomenon may be attributable to the mere communication of potential adverse effects in the informed consent process.8 This is known as the nocebo response. It may explain the consistent observation that about one-quarter of patients assigned to the placebo arm of any randomized controlled trial of a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) routinely developed the gastrointestinal side effects of the comparator NSAID. In another study comparing aspirin to sulfinpyrazone for the treatment of unstable angina, the authors found that the inclusion of possible gastrointestinal side effects in the consent forms resulted in a six-fold increase in both the frequency of these symptoms and the number of patient withdrawals from the study.9