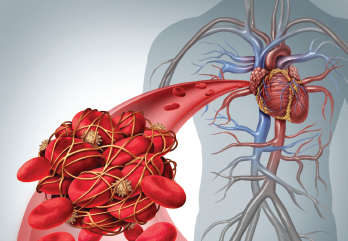

Lightspring / shutterstock.com

CHICAGO—Choosing a treatment for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) involves an array of factors, from the antibodies present to their titers to other risk factors, said Lisa Sammaritano, MD, during a guided tour of APS treatment at the 2019 ACR State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium, held April 5–7.

Dr. Sammaritano, associate attending physician at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, said the proposed pathogenesis of APS is complicated. It may involve local inflammation, vasculopathy and pregnancy complications—not just thrombosis.

“This [complication] is helpful to think about when we talk about potential non-anticoagulant therapies for this syndrome going forward,” said Dr. Sammaritano, who also discussed how to assess the risk of thrombosis, asymptomatic treatment and secondary thrombosis prevention in APS.

Assessing an APS patient’s thrombosis risk is not straightforward, she said, noting, “That is actually quite hard to define, mainly because of their other risk factors.”

Risk Factors

Patients are at high risk for thrombosis if they are positive for lupus anticoagulant antibodies. Additionally, patients are especially at risk if they’re triple positive, which means being positive for lupus anticoagulant, anti-cardiolipin and anti-beta2 GPI antibodies. The persistence of antibody titers and other risk factors, such as having lupus, cardiovascular risk factors or smoking, also play important roles, Dr. Sammaritano said.

Patients with antiphospholipid antibodies who are otherwise healthy have less than a 1% chance per year of developing thrombosis. But this risk factor can rise to 10% per year in women with a history of recurrent fetal loss and to more than 10% in patients with a history of venous thrombosis who stopped anticoagulant medication within six months.1

The odds ratio of venous thrombosis for those who are lupus anticoagulant positive is more than 6 and for arterial thrombosis, it’s 3.58. For triple positivity, the odds ratio is 33.

For women with antiphospholipid antibodies, the risk of morbidity in pregnancy is assessed similarly, with positive lupus anticoagulant or triple positivity carrying the gravest risks, while other factors also heighten risk, Dr. Sammaritano said.

Treatment

Dr. Sammaritano

Whether to start preventive treatment for patients who have antiphospholipid antibodies but no symptoms is one of the more controversial questions in the field.

“There are no good data that support using medication in an asymptomatic, antiphospholipid-positive individual,” Dr. Sammaritano said. “However, there are many studies that suggest [a benefit].”

A randomized, controlled trial found no benefit for the use of low-dose aspirin in APS patients. A meta-analysis found low-dose aspirin helps prevent a first arterial thrombosis, but not venous thrombosis.

“Our recommendation at this point is to [prescribe] low-dose aspirin [for] patients who have a high-risk profile—say they’re triple positive or [have] a very strong lupus anticoagulant [with or without the] presence of other thrombotic risk factors,” Dr. Sammaritano said. “This [decision] becomes very much a discussion between the physician and the patient, so the patient understands there’s no clear way to assess the benefit of [low-dose aspirin therapy]. But you can certainly talk to them about the relative risks in terms of bleeding.”

In patients with lupus, the recommendation for low-dose aspirin is stronger, she said.

Patients who are pregnant and have APS are routinely followed during pregnancy and anticoagulated for six to 12 weeks post-pregnancy, after which treatment is stopped. But Dr. Sammaritano noted a role for further treatment may exist. “If I have patients with obstetric APS, especially who have a high-risk profile, I routinely suggest they continue low-dose aspirin,” she said.

For secondary prevention of unprovoked venous thrombosis, she recommends lifelong warfarin, with a moderate goal of a 2.0 to 3.0 international normalized ratio. But she cautioned the literature on this approach is not clear. Her recommendation is based on a trial in which a high-intensity warfarin group was compared with a moderate-intensity group. The high-intensity group had subtherapeutic levels of the drug about half the time and, therefore, the comparison was less than optimal.2

“It’s a little bit hard to be 100% convinced this, in fact, proves moderate intensity is as effective [as high intensity],” Dr. Sammaritano said.

To prevent recurrent arterial thromboses, the most telling data come from a Japanese study of 20 patients from a cohort that fits the profile of a patient most clinicians will likely see. On average, the study patients were younger than 50, she said. The non-stroke survival was 25% in the aspirin group compared with 74% in the combination warfarin and aspirin group.3

Her recommendation for these patients is lifelong warfarin with an international normalized ratio goal of 3.0 to 4.0, or low-dose aspirin with a moderate warfarin goal of a 2.0 to 3.0 international normalized ratio.

Dr. Sammaritano said she is frequently asked whether direct oral anticoagulants have a role in such patients. Understandably so, because the treatments are convenient. But the 2018 TRAPS study of rivaroxaban vs. warfarin in high-risk patients—all triple positive—was stopped early after the cumulative incidence of death, thromboembolism and major bleeding in the rivaroxaban group outpaced the warfarin group.4

“I do not recommend changing to a direct oral anticoagulant at this time for our patients with APS,” she said

For treatment of APS in pregnancy, Dr. Sammaritano’s main message was to use low-dose aspirin in combination with low-dose heparin, usually enoxaparin, when there is more risk involved for the patient. Combination therapy is standard for patients who have had complications of obstetric APS, such as recurrent early, or a single later, fetal loss. The treatment approach may be considered for high-risk individuals who do not meet standard obstetric APS criteria in some cases, however, she said.

“If your patients have a lot of risk factors, we can be flexible in using combination therapy,” she said. “If they’ve had one miscarriage, but they’re 40, had to go through IVF and are triple positive, I would add enoxaparin to that patient’s [treatment] rather than wait for them to have three early miscarriages.”