(click for larger image)

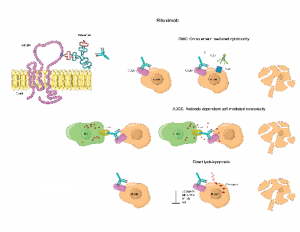

Rituximab is an antibody drug used to treat some cancers and autoimmune diseases.

ellepigrafica / SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

According to a large cohort study of pediatric patients, rituximab use is on the rise in the treatment of children diagnosed with vasculitis. Treatment with cyclophosphamide remains common, but it’s beginning to wane. Dialysis and mechanical ventilation also remain common, the study indicates.

The retrospective study of hospitalized children in the U.S. included the largest cohort of pediatric-onset anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) patients to date, according to lead author Karen E. James, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist who conducted the study while at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The researchers published the study’s results, spanning more than a decade of data, in the September issue of Arthritis Care & Research.1

AAV causes inflammation of blood vessels that can lead to organ failure (mostly in the lungs and kidneys) and life-threatening morbidity. Dr. James says medical treatment for children with AAV is often based on physician experience combined with data learned from adult-only clinical trials.

“There has been a lot of research in the past 20 years looking at ANCA-associated vasculitis and its different subtypes in adults, and there have been a lot of advances in the medicines that treat them,” says Dr. James, now an instructor in pediatric rheumatology at the University of Utah School of Medicine and Primary Children’s Medical Center in Salt Lake City. “But nobody’s really looked at it in kids, and like a lot of rheumatologic diseases, it’s rarer in kids.”

The Rise of Rituximab

Dr. James

Historically, doctors have treated adults with high doses of glucocorticoids in combination with cyclophosphamide to induce remission. Cyclophosphamide is an immunosuppressive agent doctors also use in some forms of chemotherapy, and it’s been associated with serious morbidities, such as infection, hemorrhagic cystitis, infertility and malignancy, according to the study.

The treatment landscape began to change after two landmark studies in 2010 found that rituximab was not inferior to cyclophosphamide for the induction of remission of severe AAV, says Dr. James. Later studies showed the drug also proved efficacious in maintaining remission.2,3

“Our study demonstrates a gradual decline in the use of cyclophosphamide, a gradual increase in the use of plasma exchange and an exponential increase in the use of rituximab, indicating the data from the adult studies have influenced treatment paradigms in children,” the study authors write.

Because the disease is rarer in children, pediatricians who treat these young patients with AAV may go months or longer before encountering another case. “Some places may see one of these kids every few years,” says Dr. James.

That often means a physician with experience treating a child with one effective medicine may prove reluctant to transition to a new one (e.g., rituximab) when treating the next child. Studying AAV regimens used for pediatric patients across the nation brings an understanding to actual practices and how they vary, says Dr. James, noting that different ways exist to treat diseases.

The Study

In this study, researchers reviewed data from 2004–2014 involving pediatric patients hospitalized with AAV. Using an administrative and billing database from 47 tertiary care pediatric hospitals throughout the country, the researchers examined factors surrounding the initial hospitalization and initial treatments for children later discharged with a diagnosis code of AAV.

Of 523 pediatric patients screened, 393 met the study criteria, which targeted newly diagnosed patients with active disease and those with a new relapse of disease. The average age of study participants was approximately 14 years old, and slightly more girls (61%) than boys were included. The average time in the hospital was nine days for first admissions, and about twice that for patients needing dialysis and/or mechanical ventilation.

“These are patients who haven’t been admitted in six months,” Dr. James says about those included in her study. “Either they are [newly diagnosed], or they’re [experiencing disease] flares.”

Doctors generally give induction treatments to both newly diagnosed patients and those who experience a flare. Thus, the study targeted patients who had received similar therapy.

“You get … an induction treatment,” says Dr. James, explaining typical therapy for pediatric patients in the study. “Things are quiet. You get on a maintenance medication. Maybe you are still on the maintenance or maybe you’ve come off it, and you have a flare of disease and you go back to induction.”

Researchers tracked how many patients received cyclophosphamide and rituximab and whether use of the drugs increased or decreased over the years. It also considered other treatment factors, such as the need for dialysis and mechanical ventilation, and use of plasma exchange, an additional option often used for the sickest patients.

“There was an increasing trend in the use of rituximab over time during the study period (P<0.05) and a decreasing trend in the use of cyclophosphamide (P<0.05),” the article states. “Treatment use varied significantly between hospitals, especially for plasma exchange.”

More children received cyclophosphamide than rituximab (57% vs. 21%), and 10% received a combination of both. However, the use of rituximab increased over time, notably beginning in 2011, one year after the 2010 landmark studies, says Dr. James. “We did see rituximab use was more common in hospitals that had a higher volume of ANCA vasculitis patients,” she says. “We viewed that as a marker of familiarity with treating patients. So the more patients they treated, the more likely they were to use rituximab.”

The researchers used mechanical ventilation and dialysis as surrogate markers for the severe disease manifestations of renal failure and respiratory failure. Roughly 15% of the study’s patients required dialysis, and 17% needed mechanical ventilation. Researchers found that 21% of the patients received plasma exchange and that its use was highly variable and associated with needing dialysis.

“The treatment of children with severe AAV is shifting from cyclophosphamide to rituximab, and their need for dialysis, mechanical ventilation and prolonged hospitalization remains common,” the article concluded. “Use of plasma exchange is highly variable.”

Going Forward

Dr. James says the study gives pediatricians “great understanding” of the illness severity and variability that exists in this pediatric population. “I think this research helps show other providers that yes, people are adopting rituximab, and it’s OK to do that,” she says.

“We have a lot of work to do in … figuring out what is best for kids so that people feel comfortable using these regimens,” she says. “Something needs to be done to treat these kids because they are so sick.”

Catherine Kolonko is a medical writer based in Oregon.

References

- James KE, Xiao R, Merkel PA, et al. Variation in the treatment of children hospitalized with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis in the United States. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017 Sep;69(9):1377–1383.

- Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 15;363(3):221–232.

- Jones RB, Furuta S, Tervaert JW, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis: 2-year results of a randomized trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Jun;74(6):1178–1182.