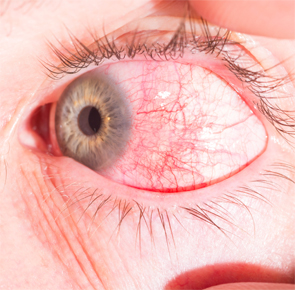

ARZTSAMUI/shutterstock.com

Ophthalmologists may be more likely to initially diagnose and treat scleritis, an inflammation of the scleral tissues of the eye. However, rheumatologists need to remain aware of the condition as well: It’s commonly associated with rheumatic disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Scleritis can present in the eye anteriorly or posteriorly. “Anterior scleritis can be diffuse, nodular, necrotizing with inflammation and necrotizing without inflammation,” says ophthalmologist Gaston O. Lacayo, III, MD, Center for Excellence in Eyecare, Miami. “The most common clinical forms are diffuse scleritis and nodular scleritis.”

Although necrotizing scleritis is less common, it’s more ominous and frequently associated with systemic autoimmune disorders, Dr. Lacayo says.

There is also posterior scleritis, which is characterized by the flattening of the choroid and sclera and retrobulbar edema, Dr. Lacayo says. Posterior scleritis can negatively affect the vision, and it can be difficult to diagnose because it is not always seen during a slitlamp examination, says Esen K. Akpek, MD, The Bendann Family Professor of Ophthalmology and Rheumatology, and associate director, Johns Hopkins Jerome L. Greene Sjögren’s Syndrome Center, The Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore.

Scleritis Symptoms

The symptoms of scleritis coincide with a number of eye problems. “It’s mostly redness and eye pain,” Dr. Akpek says. “The patients might get blurred vision if the posterior sclera is involved. Sometimes the inflammation spills over to the anterior chamber, causing uveitis. That also can cause blurred vision,” Dr. Akpek says.

If not treated properly, scleritis leads to blindness in severe cases.

Eye pain is sometimes so bad at night, it can cause trouble sleeping, says rheumatologist Elyse Rubenstein, MD, Providence Saint John’s Health Center, Santa Monica, Calif. Headaches and photophobia are other possible symptoms of scleritis.

These same symptoms can accompany conjunctivitis, iritis, keratitis, uveitis, herpes zoster and corneal melt, among other ocular disorders, Dr. Rubenstein says.

Treating physicians must also make the distinction between scleritis and the more benign episcleritis. “The redness in episcleritis is a brighter red, and in scleritis, it’s more bluish red,” Dr. Akpek says. “Also, with the exam, there’s scleral edema and deep episcleral vascular engorgement with scleritis.”

Slitlamp examination detects the intraocular inflammation in scleritis and assesses severity. CT scan, MRI and ultrasound are sometimes necessary to help determine the extent of involvement and make a differential diagnosis, says rheumatologist Anca Askanase, MD, clinical director and founder of the new Lupus Center at Columbia University Medical Center, New York.

About half the time, scleritis occurs in both eyes; recurrences are common, Dr. Askanase says.

Rheumatic Disease & Scleritis

About half of the patients who have scleritis have associated rheumatic disease.

“Scleritis can occur in a number of systemic inflammatory diseases, more often in patients with an established diagnosis who develop ocular symptoms and are diagnosed by an ophthalmologist,” says rheumatologist Christopher Wise, MD, professor, internal medicine, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Va.

Because RA is the most common form of chronic inflammatory arthritis seen by rheumatologists, that’s also the condition most often associated with scleritis, particularly in patients with severe RA, Dr. Wise says. However, he also believes the number of RA-associated scleritis cases is decreasing due to more effective RA therapies now available.

Other conditions associated with scleritis include inflammatory arthropathies, lupus and related autoimmune diseases, and systemic vasculitis. Sjögren’s syndrome is an underdiagnosed condition that can be associated with scleritis, Dr. Akpek says.

Cases of scleritis associated with previously undiagnosed granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) are important to catch, because GPA can be fatal if not treated, says ophthalmologist John D. Sheppard, MD, president of Virginia Eye Consultants, and professor of ophthalmology, microbiology and molecular biology, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, Va.

Treatment of Scleritis

Quick diagnosis and treatment of scleritis is essential to avoid debilitating visual consequences. “Corneal melts and scleral perforations are sight-threatening sequelae of uncontrolled scleritis. The correct and rapid diagnosis and the appropriate systemic therapy can halt the relentless progression of both ocular and systemic processes, preventing destruction of the globe and prolonging survival,” Dr. Lacayo says.

Treatment for scleritis depends on identifying the source of systemic inflammation with bloodwork. Systemic or oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), systemic steroids and immunosuppressive agents, such as methotrexate, cyclosporine and azathioprine, are part of the treatment combination, Dr. Lacayo says.

Physicians must know if a patient has glaucoma or a previous ocular herpetic infection, as well as renal, gastric, hepatic, hematologic or tuberculous disease, because those conditions can limit the treatment options, Dr. Sheppard says.

If the cause of scleritis is unknown, first-line treatment often is oral NSAIDs; if there is underlying collagen vascular disease, immunosuppression may be required. “In general, controlling the systemic disease results in control of the ocular inflammation,” Dr. Askanase says.

Another scleritis cause that leads to a different treatment course is infection—be it viral, bacterial, fungal or parasitic; Lyme disease should also be considered, Dr. Askanase says. Sometimes, the cause of scleritis cannot be identified.

The Rheumatologist’s Role

In the most common scenario, a patient with scleritis presents to an ophthalmology clinic, not to the rheumatologist; patients with rheumatic disease usually already have their condition diagnosed, Dr. Akpek observed.

Another common scenario is a scleritis patient who presents to the ER and receives topical antibiotics, and they show up weeks later to see the ophthalmologist or rheumatologist in dire straits, Dr. Sheppard says.

Ophthalmologists usually are proactive about referring scleritis patients with no diagnosed systemic disease to rheumatologists for evaluation.

Rheumatologists will begin their examination of scleritis patients with a careful history and physical exam, with an emphasis on the musculoskeletal, dermatologic, cardiopulmonary, upper airway, neurologic and renal systems, Dr. Wise says.

Initial lab studies include complete blood count, serum chemistries, inflammatory markers, a chest X-ray and a battery of serologic tests for RA, lupus and related diseases.

“The serologic studies are often helpful if positive, even in patients without obvious clinical features of an underlying disease, [because] scleritis can be the initial manifestation of the condition,” Dr. Wise says.

There is always a need for close collaboration between rheumatologists and ophthalmologists to manage the condition.

First, rheumatologists should keep a close eye on their patients’ eyes, Dr. Lacayo advised. “Scleral tissue should be mostly white in all healthy individuals. Any small amount of scleral injection or recurrent hyperemia should tip the rheumatologist toward stronger or longer treatments with the agents mentioned,” he says.

“In the case that a rheumatologist sees a patient with a red, painful eye, they should send the patient to an ophthalmologist for evaluation,” Dr. Akpek says.

Yet ophthalmologists must stay aware of the need for a referral as well. During therapy, ophthalmologists often consult rheumatologists if a patient’s response to systemic steroid therapy is incomplete or temporary, or if the patient cannot taper steroids without an exacerbation, Dr. Wise says.

“If a patient presents with scleritis associated with joint pain, rash or shortness of breath, fatigue or other systemic complaints, they should be referred to a rheumatologist for evaluation,” Dr. Rubenstein says.

Although there are no new scleritis-specific treatments on the horizon, adalimumab (Humira) is on the cusp of being approved for uveitis, Dr. Sheppard says. This is valuable to know because he finds that uveitis treatments are often effective for scleritis patients. “This condition always takes a back seat to uveitis, but a lot of companies are investigating uveitis to the potential benefit of our scleritis patients as well,” he says.

Vanessa Caceres is a medical writer in Bradenton, Fla.