PRES

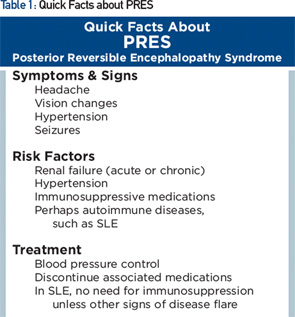

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is characterized by subacute onset of headache, seizure, encephalopathy or visual disturbance, with neuroimaging showing reversible subcortical vasogenic edema (see Table 1). Although PRES was named as such in 1996, the disorder had been known for many years, initially as hypertensive encephalopathy and then as reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy.

Clinically, seizures are the most common mode of presentation, occurring in about 75% or more. Visual disturbance is cortically mediated and can take the form of cortical blindness, visual neglect or higher order visual processing difficulty (e.g., simultagnosia, in which patients can identify parts of a picture but not put together the entire picture—identify the trees, but not the forest). The most common imaging feature on MRI is presence of relatively symmetric T2 hyperintensity, thought to be edema, in the posterior white matter.

Despite having “posterior” in the name, PRES can affect other regions as well, including frontal lobes, basal ganglia, the brainstem and cerebellum, as they did in our patient. Some of these changes may be apparent on head CT, but MRI is more sensitive for this condition.

PRES is associated with hypertension found in the majority of patients (mean systolic BP of about 190 mmHg). In 10% of patients, PRES can occur with systolic BP below 140 mmHg.4 Abrupt increases in BP may be pathogenic even when the absolute systolic pressure is not that high. Hypertension alone, however, does not always cause PRES.

Other common risk factors are acute or chronic renal failure; chemotherapy/immunosuppressive medication, including cyclophosphamide, calcineurin inhibitors and methotrexate; bevacizumab; and eclampsia.

Many patients with PRES have concurrent autoimmune disorders, estimated at 45% in case series, including SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma and ulcerative colitis. Some of these conditions, however, are also associated with use of immunosuppressive medications, hypertension or renal dysfunction. The relative contribution of the underlying autoimmune disorder vs. its complications in predisposing to PRES is uncertain. Our patient, for example, had risk factors of preceding renal dysfunction and prior use of immunosuppressive medications.

There is a growing literature of cases of PRES occurring in patients with SLE, some in the absence of renal dysfunction or immunosuppressive medications, suggesting that SLE alone may also be a risk factor.5 Further epidemiologic studies are needed to clarify the relationship.

In PRES, there is dysfunction of cerebral vascular autoregulation and breakdown of the blood–brain barrier. The cause of this dysregulation is unclear, but it’s hypothesized to result from endothelial injury, such as from rapid rise in BP or vasospasm from circulating toxins. So far, there is no evidence of inflammation contributing to PRES.