Image Credit: design36/shutterstock.com

As a rheumatologist, you’re used to having goals. After all, you set your sights on becoming a physician, achieved the necessary educational degrees and passed required exams. After meeting your educational goals, you landed a job at an academic medical center or an established rheumatology practice, or you may have started your own practice.

So what now? Should you put yourself on cruise control and coast until retirement?

Hardly, says Stephen A. Paget, MD, FACP, FACR, MACR, physician-in-chief and chair of the Division of Rheumatology at the Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) in New York. “Without specific goals, you will flail about aimlessly at every phase of your career, waste time and money, and never attain the end that you desire. It would be like taking a long trip without a map,” says Dr. Paget. “You need to have a starting point, a goal for the future and then develop a map to achieve that goal.”

“Ideally, at each phase of your career, you should think ahead and decide where you want to be in one year, three years, five years, 10 years and afterward, and then set specific goals and approaches to attain your goals,” Dr. Paget continues. “It is important to set milestones along the path to achieve your goals.”

Ms. Wright

Christy Wright, speaker and certified business and life coach at the financial consulting firm Ramsey Solutions in Nashville, Tenn., cites additional reasons to set goals. “If you want to advance your career, make more money, have more opportunities and grow as a professional, goals will help you make those things happen,” she says. “Goals provide clarity, direction and accountability. They also help you measure your progress to make sure that you’re on the right track.”

Mr. Fritsch

Michael Fritsch, PMP, president and COO at the consulting and professional services company, Confoe, in Austin, Tex., adds that setting goals can help you prioritize. “[Setting goals] helps ensure that important items don’t get lost or neglected in the day-to-day scramble to get your job done,” he says. “For professional development, goal setting is even more important because it’s easy to delay increasing [your] professional skills or credentials if you don’t make it a priority.”

From a psychological standpoint, goals enable us to make progress, and as humans, we are naturally wired for progress, Ms. Wright continues. “When we feel stagnant and stuck in an area of our lives, we get frustrated,” she says. Having something to work toward gives us a sense of purpose, and provides challenges and learning and growth opportunities, which are vital to developing a healthy sense of self-worth and self-esteem. Goals are critical for many positive personal qualities, as well as a fulfilled life.

Setting Professional Goals

The start of a new year is a good time to set professional goals. When setting career goals, Dr. Paget says you need to have a sense of who you are, what your strengths and weaknesses are and what you most enjoy doing. “There are many paths to take to achieve your goals, and they differ greatly depending on whether you want to be a clinician, physician–scientist, medical educator, chair of a department or a dean of a medical center,” he says. “Speak to your mentors to get their sense of your strengths and weaknesses and [help determine] where you might best focus your efforts.”

Reflecting on professional goals that he has set, Dr. Paget says he always wanted to be part of an academic institution and in a leadership position. In order to achieve this, he needed to take a certain path, which meant applying himself early on to excel as a medical student, resident and fellow wherever possible; becoming involved in research; joining both hospital and national committees to optimize his network; taking courses that would enhance his abilities and make him more professionally attractive; and seeking out the guidance of trusted mentors who could help him choose and attain a goal.

Dr. paget

Dr. Paget is pleased to report that he has achieved all of his career goals to date, beginning with graduating as the valedictorian of his medical school class and training in internal medicine at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. He has been a clinical associate at the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases in Bethesda, Md., served as a fellow at HSS, participated in clinical research, published nearly 100 articles, became a training program director and eventually chair of the department and, more recently, directed an academy of medical educators.

“I was recently a graduate student at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health [in New York] with the goal of attaining a Master’s of Public Health degree because I felt that the next phase of my career, at age 70, demanded more intensive knowledge about clinical investigation and public health,” Dr. Paget says.

Be Realistic

Dr. Paget has achieved his goals because he was willing to put in the time, energy and commitment to accomplish them. How can you determine if your goals are realistic?

The best starting point is to look at your past performance in a given area and stretch yourself from there, Ms. Wright suggests. For example, as a runner, her fastest pace in a half-marathon is eight minutes and 23 seconds per mile. “It would be unrealistic for me to expect to run seven-minute miles for my next half-marathon, but at the same time it would be sand-bagging to set a goal of nine minutes per mile,” she says. “If I want to set a goal of running a new personal record for my half-marathon, I could shoot for running eight minutes per mile.”

In any area of your life, look at what you’ve done in the past and how you can improve, Ms. Wright recommends. If you’re doing something for the first time, you can use past practices to set a goal, or you can make finishing a task a goal. Be realistic when you’re setting goals, and keep in mind that you’re probably capable of more than you think.

By developing an academy of medical educators at HSS, Dr. Paget set himself up for the next phase of his career. The work makes him tap administrative strengths that he gained over time, uses his experience as chair of medicine/rheumatology and requires information that he gained in his master’s program. “It’s important to note that when one door closes, another one opens. You just need to be tuned in to your professional environment so that you can find that door more easily,” he says. “Activities that I could not have done as chairman of rheumatology, I now have the time to do.”

Stay on Target

When looking to achieve your goals, consider setting goals that are SMART—specific, measurable, attainable and realistic, and have a timeframe attached. For example, wanting to lose weight is not a goal, it’s a wish. But deciding that you want to lose 15 lbs. (a specific and measurable action item) over six weeks (realistic and attainable) by June 1 (time limit) is a goal. “When you set SMART goals, you set yourself up for success in meeting them,” Ms. Wright says.

Mr. Flahiff

Joseph Flahiff, a leadership coach and founder of Whitewater Projects Inc., in Bothell, Wash., a company that helps leaders of organizations quickly adapt to changing industries and markets, advises taking a large goal and breaking it into smaller, achievable goals. “You’ll be much more motivated to stay on target” by doing so, he says. “When you try to do things that are merely tasks that don’t give you a sense of accomplishment, you are less likely to finish them. You need that hit of dopamine. Your body is designed to give you a feeling of satisfaction for your accomplishment.”

Dr. Paget advises finding a faculty member who best exemplifies the person you want to be. “That mentor should guide you and develop a road map for your future,” he says. “If you join a medical school faculty, be aware of what achievements are needed at your specific medical school or hospital to move from instructor, to assistant professor, to associate professor and, eventually, to professor. Once you see this, you will understand exactly what is needed to achieve those goals.”

Mr. Casemore

Shawn Casemore, president and founder of the professional empowerment consulting firm, Casemore & Co. Inc., in Owen Sound, Ontario, Canada, recommends keeping key goals in front of you, such as on a sticky note at your computer or on a notepad on your night table. He also suggests writing down your goals and reviewing them daily. Add notes as time passes regarding specific actions you want to take that will support you in achieving your goals, he says.

Dr. Paget reviews his larger goals either every six months or once a year. “You have to reassess what your goals are, how many of them you have already achieved and how to attain those necessary for the next phase of your career, because sometimes life and reality get in the way and necessitate a change in course,” he says. “Each area of focus has its own demands, and you have to be sure, all the way, that you are up to the task by obtaining new knowledge, participating in research or administrative activities, publishing, joining committees and networking.”

Set a Deadline

Deadlines are a necessity. “You will not get serious about your goal, behavior or progress until you set a deadline,” Ms. Wright says. “When you set a goal, you become serious about the results and give yourself an urgency to commit to it. If you wait until it’s convenient, easy or you have nothing else to do, it will never happen. There are seven days in a week, and ‘someday’ isn’t one of them. Set a deadline, and hold yourself accountable to make your dreams a reality.”

Make sure timelines are realistic, advises Mr. Casemore. Unrealistic timelines can lead to feelings of inadequacy or a belief that the entire process is useless. “This is why most people who set a New Year’s goal to lose weight by an unrealistic timeline give up early,” he says. For example, a rheumatologist may want to double the size of their practice and set a goal to do so in six months’ time when, in reality, two years may be a more realistic timeframe. In order to set realistic timelines, seek outside validation: What have others who have achieved this goal done, and what was their timeframe to do so?

Ready, Set, Go

Although taking “Easy Street” may seem appealing, you will ultimately miss out on opportunities and won’t reach your full potential if you don’t set professional goals. You can reach your goals by making realistic goals and striving for smaller milestones along the way. Set deadlines and hold yourself accountable. Have a mentor help guide you, and assess and re-evaluate your goals on a regular basis to ensure success.

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

Get Employees on Board with Goal Setting

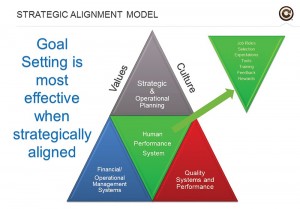

In addition to setting professional goals for yourself, it’s advantageous to ask employees to set their own goals. “When team members have goals, they have a sense of direction and purpose,” says Christy Wright, speaker and certified business and life coach at the financial consulting firm Ramsey Solutions in Nashville, Tenn. “It helps them get above the day-to-day tasks and see the bigger picture that they are working toward. It builds confidence as well as competence. It also helps them achieve more for the practice when they are challenged beyond their comfort zone.” (See Figure 1.)

(click for larger image) Figure 1: Goals are an integral part of the human performance system. When goals are aligned with an organization’s values and culture, the employee or team member can see how their goal contributes to the strategic plan of the larger organization.

Source: www.confoe.com

A leader should allow each team member to set individual goals first, Ms. Wright says, and then the leader and team member should jointly discuss why and how to achieve those goals.

Along those same lines, Shawn Casemore, president and founder of the professional empowerment consulting firm Casemore & Co. Inc., in Owen Sound, Ontario, Canada, says that practice owners must develop goals for their employees. However, the only way to obtain employee buy-in is to do so collaboratively by collectively agreeing on objectives and timelines.

Joseph Flahiff, a leadership coach and founder of Whitewater Projects, Inc., in Bothell, Wash., says having employees set goals is a good way to determine if they understand your organization’s objectives. If they do, employers can entrust the employee with more ownership and authority. “Create leaders at every level of an organization, not just at the top,” he says.

Stephen A. Paget, MD, FACP, FACR, MACR, physician-in-chief and chairman of the Division of Rheumatology at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, says academic physicians have to achieve certain goals—typically found on a college’s website—in order to move up the academic ladder from instructor to assistant professor, associate professor and full professor.

Help Employees Reach the Stars

Leaders can provide two important things when helping team members accomplish their goals: encouragement and accountability. Provide accountability by checking in with team members periodically and asking how they are doing, but also be quick to encourage them, cheer them on and give them high-fives on their progress. “When you do this, you not only build trust and loyalty with your team member, you motivate them to keep going to complete the goal,” Ms. Wright says.

Michael Fritsch, PMP, president and COO at the consulting and professional services company Confoe in Austin, Tex., says it’s essential to check on how employees are progressing toward achieving their goals by asking them for a weekly update, which he calls a “red, yellow, green approach.” In other words, how confident are they that they will accomplish the goal by the deadline? Do they need help?

For data-driven goals, Mr. Fritsch advises making current performance and performance trends visible to the employee. For example, if an employee wants to set a goal to process a certain number of insurance claims per day, provide them with a chart showing the actual number that is processed daily. If multiple team members process claims, the chart could show the performance of each team member individually so employees can see how they are doing relative to other team members. “An easy, low-tech approach would be to just have an employee write down their number each day and keep a running tally,” Mr. Fritsch says.

You can take a similar approach with anything that has a number or measurement, such as a customer service score or the number of filled prescriptions. “Be sure to balance the time and effort of measuring and reporting performance with the benefit from the visibility of that performance,” he says.

When an employee raises a flag or the data show problems, check in to see what kind of help they need, Mr. Fritsch continues. Create an environment where it is all right to ask for help or raise an issue, but still hold employees accountable and make things challenging.

Dr. Paget often checks in with individuals that he mentors on their goals and discusses the best ways to achieve them. “It is my responsibility to guide individuals that I am mentoring socially, politically, academically, scientifically and practically by helping them find and remain on the appropriate path,” he says. Dr. Paget suggests having a faculty member mentor rheumatologists in a specific area to help guide them in making their portfolio and resume as robust and compelling as possible.