In cloning our genes and enumerating our cytokines, we have neglected the lesson of Ivan Pavlov where salivation was controlled by operant conditioning more than 100 years ago and the role of the stress-axis pointed out by Hans Selye, MD, more than 80 years ago.

Immunology’s greatest advances a generation ago were based on the pivotal recognition of the immune system as part of the “Danger Hypothesis.” The most immediate product of this hypothesis was the recognition of the innate immune system with its characteristic signals of fever, blood pressure and other signs ranging from flu-like symptoms to septic shock.

Ocular and oral symptoms are among the most important “survival” traits of the species. A significant amount of cortical memory is allotted to the discrimination of “painful” stimuli, and learning to avoid such stimuli is highly refined.

At the one end of the spectrum, we still have not really understood at a molecular basis why we feel like we have been hit by a truck after a viral flu, or why we are tired and cognitively slow after a long airplane flight that we call “jet lag.”

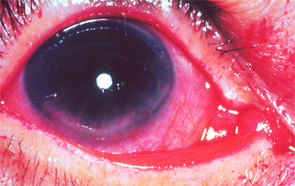

Flecks of reddish-purple discoloration are seen in the lower portion of the cornea and conjunctiva. These changes are typical of keratoconjunctivitis sicca when the eye is stained with Rose Bengal dye; they are the result of decreased tear formation and represent corneal abrasions. Corneal abrasions may be prevented by the use of artificial tears.

Image Source: Rheumatology image library

No one would accuse a symptomatic “normal” individual of malingering if these symptoms were present, but would attribute them to some disruption of neurokines by the virus (or the innate response to it) or to a readjustment of neurokines to our circadian internal clocks in the case of jet lag.

The fascinating extreme of dysfunction is “phantom pain,” as shown by Ramachandran et al, where an amputated limb “hurts.”5 This is explained at the level of brain processing (and its descending afferents) through a network called “veto neurons.” Roughly, the brain processes a variety of inputs, and the absence of a signal (such as pain or position fibers from a missing limb) is important information to the cortical memory bank. The silencing of these “nociceptive” signals is performed normally by other neurons in the brain.

An even more fascinating observation by functional magnetic resonance imaging is that these processes show up by objective (although still crude) scanning techniques.