Despite a generation of advances in molecular biology, a huge gap exists between the Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) patient’s description of their symptoms and the objective findings. Current issues include:

- Many SS patients are misclassified as either rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), even within rheumatology clinics.

- Frequently, the sickest SS patients with extraglandular manifestations, including lung, kidney and neurologic system, may be directed to other specialty clinics (e.g., Pulmonary, Renal, Hematology) where the illness is mislabeled as SLE or idiopathic.

- As a result, our SS clinical trials are biased toward SS patients with only sicca complaints and fatigue—the manifestations least likely to show benefits in trials studying biologics or other novel immunomodulation agents.

- As a result of these factors (see Table 1, right), there has been growing discouragement among both patients and rheumatologists about the likelihood of discovering novel therapies for SS.

Steps for the future: First, improvement in identifying SS patients will require relabeling the interpretation of the ANA (the gold standard is immune fluorescent antibody method or IFA) as suggestive of SLE or SS.

- A reflex antibody to SS-A/B should be performed if ANA by IFA is positive.

- If the ANA is negative by enzyme-linked immune assay (ELISA), then a reflex antibody to SS-A/B should still be performed, since the ANA by ELISA test may fail to identify the SS-A/B antibody.

Second, we have become prisoner to the paradigm of symptoms and acute-phase reactants, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP).

- This follows from a decade of understanding T cell-mediated mechanisms of antigen-dependent-driven processes.

However, this model clearly does not help in judging activity of central nervous system (CNS) processes in known autoimmune disorders such as multiple sclerosis (MS). We must understand how neural-mediated transmitters play a role in the CNS.

Third, we must develop an understanding of the “neuro-immune” interface that governs the cortical sensation of dryness or pain.

- Our failures in better managing neuropathic pain become very evident when managing our patients with SS.

- Thus, a better collaboration between rheumatology and other medical specialties, such as neurology, and pain medicine for clinical trials should improve the outlook for the next decade’s therapy.

In a previous issue of The Rheumatologist (November 2013), we described a model of “phantom pain” and how it might play a role in the difference between patients’ symptoms and objective findings.

Background

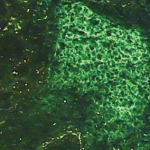

In this patient with Sjögren’s syndrome, most of the parotid gland parenchyma has been replaced by a diffuse collection of lymphocytes, which sometimes leads to an erroneous histologic diagnosis of malignant lymphoma. The lumen of the salivary ductule in the center of the field is occluded by an eosinophilic deposit of inspissated or thickened secretion; the duct lining cells are markedly hyperplastic (epimyoepithelial islands).

Image Credit: Rheumatology image library

Sjögren’s syndrome is primarily characterized by serious and often disabling dry eyes and dry mouth due to immune infiltration of target organs.

The 2015 XIII International Sjögren’s Symposium in Bergen, Norway, highlighted the great advances since the first SS symposium was held in 1986 with a handful of rheumatologists, ophthalmologists and oral medicine specialists in attendance. To put the timing of the initial meeting in perspective, all attendees at the 1986 symposium were “hosed down” several times a day due to the radioactive fallout from the then-recent Chernobyl meltdown.

Participants at the first symposium included Roland Jonssen, Troy Daniels, John Greenspan, Claudio Vitali and the author. Many were also at the most recent SS meeting in Bergen to pass the torch to a new generation of researchers. We also took time at the recent meeting to note the absence of many organizers of the original meeting, such as Norman Talal, Peter Oxholme, Jan Waldenstrom and even Henrik Sjögren. Actually, Sjögren was ill on the day of the initial meeting, so a number of us drove over to his home to give him our greetings.

Thus, the recent SS symposium in Bergen provides an appropriate prompt for us to look at where we are currently in terms of our understanding of pathogenesis and treatment.

A review of the scientific presentations and the full abstracts are referenced in a recent article by the author in WebMD.

So where are we now, after thousands of articles about innumerable genes and cytokines?

The basic clinical features of Sjögren’s were outlined by Bloch et al in 1956, and we have a couple of medications for topical dryness—topical cyclosporine and oral cevimeline or pilocarpine.1

Rituximab (Rituxan) remains the most widely administered biologic drug for the extraglandular manifestations in U.S. clinical practice and in large cohorts of patients in France, but it did not show significant improvement in a pivotal randomized prospective trial in the U.S., and thus was not even submitted to the FDA.2,3

Why do we have this phenomenal disconnect between clinical practice and FDA approval in the U.S., where rheumatologists must use innovative ICD coding to treat SS patients with a therapy widely used for SS in Europe?4

The simple answer is that few SS patients in the U.S. prospective rituximab trials had extraglandular symptoms and that drug may not need to be used in a “preventive” prospective method, as is done in the treatment of RA. We treat lymphoma when it becomes apparent and not before it is confirmed.

SS patients in rituximab trials did not show improvement in their “fibromyalgia” symptoms that were the predominant feature of these study cohorts.

Thus, U.S. rheumatologists “sneak around” to give this medication in potentially life-threatening extraglandular manifestations over the increasingly loud threats of insurance carriers.

Clinical Presentations & Their Economic Costs

Sjögren’s has both benign and systemic manifestations.

Benign manifestations include dry eyes, dry mouth and fatigue/cognitive impairment. Although we call these benign, they are the greatest self-described problems for SS patients, and patients equate these symptoms’ impact on their lives at the level of “moderate angina.” Thus, our conclusion is that benign symptoms are not benign in their impact on a patient’s quality of life or the economic impact they have.

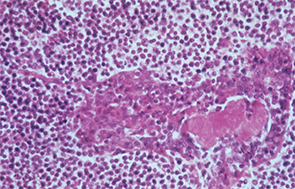

For the patient with SS, the economic impact of dry eyes and lost productivity occurs in an era when many patients work at computers and in low-humidity office buildings. Pollution has exacerbated the problem. “Dry or painful eyes” is often cited as the single most common reason for a visit to an ophthalmologist.

Estimates of lost productivity due to ocular dryness exceed £160 million (≈$247,472,000) in the UK alone. As more individuals spend eight or more hours a day at computers, the costs will get even greater. Eye-blink rate decreases by 90% when staring at a computer monitor, further exacerbating the problem of ocular discomfort and ocular fatigue.

Indeed, each of us has experienced the sensation of taking off our glasses to gently massage our weary eyes while we pore over work or are affixed to a mobile device. We are actually stimulating the minor lacrimal glands to increase tearing, and we do not even have a “dysfunctional” tear film.

Our therapies for dry eyes remain the same or marginally better than 30 years ago. Basically, we have learned that preserved tears used more frequently than four times a day can create irritation due to their preservative, and thus, “preservative-free” artificial tears have emerged, which are much more expensive.

Although we have made a great deal of progress in understanding the tear film and the mechanisms of inflammation that result from and perpetuate a “dysfunctional tear syndrome,” we have only one approved therapy for dry eyes (topical cyclosporin, Restasis), which was approved by the FDA on the basis that it raised the tear flow rate (Schirmer’s test) from 1 mm to 2 mm. I doubt that any of us could even tell the difference in that measurement at bedside.

The mainstay of dry eyes remains “artificial tears” and recognition/treatment of blepharitis. A trip to the local pharmacy will reveal an intimidating floor-to-ceiling display of an array of brands of artificial tear products that vary in preservative, “wetting agent” and price. The average rheumatologist offers the sage advice to “try a few different types and see what you like best.”

Although we can advise about the latest genetic polymorphism reported in the journals, we remain clueless about how to advise the patient on rationally treating their ocular “disability.”

A wide variety of artificial tears have gone through clinical trials, and some promising new candidates are nearing FDA approval, but we will still have a wide gap between patient complaints and adequate therapy. Also, novel approaches, such as electrical stimulation of lacrimal glands, are being investigated.

However, I think the main breakthroughs in the next decade for the majority of SS patients will come with improved understanding of how the brain perceives the sensation of dryness at the cortical level (discussed below), because we see an enormous overlap between patients with symptoms and relatively few objective signs, and patients with dysfunctional tear films, but few symptoms.

The ocular receptors mediating dryness (evaporative loss) have been cloned, and their neural circuits have been mapped. However, the time has come to apply the lessons of neurochemistry and neuropathology to the humble task of “cracking the therapeutic code” of dry eye discomfort, which is not nearly as seductive a topic for research grants as demyelinating disorders, but has a much greater social and economic impact.

Dry mouth and dental decay remain enormous expenses (such as dental implants) that are not covered by medical or dental insurance. We do not have time to even take into account the disruptions of social interactions when patients cannot socialize around food with their friends and families. Given that approximately 90% of SS patients are female, this impact is critical.

Although not about Sjögren’s syndrome directly, the movie Eat Drink Man Woman, produced by Ang Lee, poignantly called attention to the important social relationships around food and socialization. This film examines the social interactions at family dinners and their importance in the culture and socialization of the family when the father (a chef) loses his ability to taste or smell the food he prepares. An SS patient cannot enjoy the same foods or even chew the same meat as others. Thus, their participation in the important social interactions around food is limited, and they withdraw from this important social support system, which is paramount to their overall emotional well-being.

Over the past decade, our understanding of diet and oral symptoms has evolved. Due to dryness, there is not only change in swallowing and taste, but also changes in the pattern of secreted salivary proteins (the saliva proteome).

Additionally, there is a significant change in the oral bacterial environment (the oral biomone) of the mouth. So in addition to the adverse role that sugars play in the acceleration of tooth decay, we now see objective changes in the mouth’s bacterial environment in combination with decreases in the normal mucosal defense barriers.

Most of these studies were published in the radiation therapy literature that we rarely read. Consequently, we will have to do our homework to understand how to repair the normal flora, decrease dental decay and increase the regrowth of “taste buds.”

We will also have to expand our understanding of the diurnal variations that lead to decreases in saliva production (as well as ocular tearing) at night, and to recognize the adverse effects of many other common medications (e.g., those for blood pressure, sleep) on these diurnal rhythms.

Many of these simple clinical hints are already known to radiation therapists and dental hygienists, but the limited time allocated at the rheumatology visit simply does not permit such patient education. This is a job for which Internet education and the multitude of SS-related patient support YouTube videos may play a significant role.

Diagnosis & Classification

Our sickest patients often are not seen in a rheumatology clinic or are mislabeled as SLE or RA. One trick question for rheumatologists is: “Does a positive SS-A antibody fulfill the criteria for SLE?” The majority will incorrectly answer “yes.”

When you expand the group to hematologists and then to orthopedic surgeons (a predominance of the world’s patients are cared for by “non-operative” orthopedists), the results become pretty close to random answers.

Systemic manifestations are diverse and may be misclassified as either RA or SLE.

In terms of systemic manifestations, our SS patients have a wide spectrum of them. The most common differential is between SLE, RA and scleroderma (and there also is often a great deal of overlap).

Given the considerable clinical and therapeutic overlap between SLE and SS, it’s useful to keep them as separate diagnostic concepts in order to maintain vigilance about the distinct ocular, oral and extraglandular manifestations pertaining to both. For example:

- I roughly think of SLE as an immune complex disorder and SS as an aggressive lymphocyte disorder.

- While the SLE patient has pleurisy, the SS patient has interstitial pneumonitis.

- While the SLE patient has glomerulonephritis, the SS patient has interstitial nephritis.

- The incidence of lymphoma, as well as parotid/submandibular swelling, is much higher in the SS patient.

When a patient has severe nephritis or pneumonitis or myelitis, no one really ever asks if they have dry mouth. The most important mistake made in the primary care clinic is that a “mandatory” ANA or RF is drawn as part of the work-up. When either comes back positive, the result will be labeled “consider SLE” (or “RA”) in the tiny footnote by the asterisk.

Also, the now popular ANA by ELISA may not detect the ANA positive by immunofluorescence, and the “reflex” SS-A antibody is never obtained.

Indeed, the entire syndrome of “subacute lupus” (ANA-negative, SS-A positive) simply derives from the artifactual denaturation of the SS-A antigen during fixation of the slides for immunofixation.

We are continually confronted with the patient whose ANA was positive in one lab, while negative in another lab. It is more likely that this is due to the laboratory method employed than to significant alterations in the patient’s serology.

A poorly appreciated variable is “who draws the screening laboratory test.” I will present an example in the form of a joke.

Three rheumatologists—an American, a Japanese and a European—visit an epidemiologist to compare the results of their clinical cohorts. Each rheumatologist notes a different frequency of extraglandular manifestations and differences in their cohorts. The initial suspicion that leaps to mind is, “Does this reflect a difference in their genes or environment, such as food intake?”

Perhaps, but a simpler explanation may play a part. In fact, after years of having these discussions, I think most commonly it depends on who orders the ANA and RF blood tests.

The American patient with complaints of fatigue has the ANA drawn by the family practice doctor or nurse practitioner—who sends the patient off to rheumatology clinic. The wait is up to six months to be seen, and anyone really sick (renal, pulmonary, hematologic, neurologic) is sent to the other specialty clinic, where they are diagnosed with SLE or RA—never to be reclassified.

The Japanese patient has a better chance of being labeled as SS, because the primary care doctors send patients to the rheumatology clinic based on symptoms of rash or arthritis, and the rheumatologist (but not the primary care doctor) is allowed to order the ANA panel.

The Indian patient in large medical centers has to be really sick to even make it through triage to a clinic, where dry eyes and mouth are an annoyance rather than a condition, such as uveitis. Once in the Indian rheumatology clinic, the number

of rheumatologists is so meager and the cost of care so prohibitive that the potential for follow-up for prior problems is limited at best.

European rheumatologists, whose grants are not generally judged on the number of cytokines cloned since the last review, have quietly been organizing their patients into cohorts and cross-referencing to normal health data banks. The basis for grants is cooperation rather than the number of cytokines examined.

Also, clinical cohorts in Europe appear to relocate less frequently than do Americans, and their healthcare system allows easier access to follow-up. As a result, the current data available are now largely based on the slow, but steady, clinical advances made by these European groups.

The greatest nightmare in rheumatology clinic is the SS patient with vague neurologic symptoms. The patient describes many complaints that limit their quality of life and few objective laboratory abnormalities. We grew up in an age of RA with high ESR and CRP or SLE with glomerulonephritis. Each of these conditions was suitable for double-blind studies with straightforward procedures and outcomes.

We were never exposed to multiple sclerosis patients whose dry eyes, vague neuropathic pains and fatigue were not accompanied by elevation of acute-phase reactants … but at least the neurologists had the tool chest of abnormal brain MRIs and cerebral spinal fluids to confirm their diagnoses.

In our SS patients, we have yet to find the surrogate markers that correlate with their symptoms, so we ignore them and continue to propose the same types of therapeutic protocols that have failed in the past.

Sometimes, these vague CNS symptoms in the SS patient even respond to a trial of corticosteroids. We might assume this reflects an autoimmune component, and it may indeed play a role, just as early studies of multiple sclerosis used high-dose corticosteroids. But we need to consider that corticosteroids have a host of other applications and effects, such as their use in the adrenocortical axis or neuronal swelling (i.e., post-concussive injury).

Other uses of steroids, such as for asthma or allergic attacks, are probably mediated through pathways that don’t use traditional innate or acquired immunity. We know that some patients develop agitation on steroids, so there must be CNS effects at a molecular level that we have yet to understand.

We should humbly remember that we still do not understand the reasons for myalgia and fatigue after a common cold.

The big questions for the next decade: Understanding the disconnect between objective findings and subjective findings, particularly in “benign” manifestations.

We have all been in an exam room with a patient complaining of dry eyes while constantly instilling artificial tears or complaining of horrible dry mouth while our manual exam is relatively mild (at least in the old days when time allotted per visit allowed such activities as objectively confirming a patient’s complaint). I believe this “disconnect between objective and subjective” is a critical question (and the reason for our failures in clinical trials). I suspect the answers lie largely in the domain of “pain management” and current “neuro-behavioral” biological research.

In cloning our genes and enumerating our cytokines, we have neglected the lesson of Ivan Pavlov where salivation was controlled by operant conditioning more than 100 years ago and the role of the stress-axis pointed out by Hans Selye, MD, more than 80 years ago.

Immunology’s greatest advances a generation ago were based on the pivotal recognition of the immune system as part of the “Danger Hypothesis.” The most immediate product of this hypothesis was the recognition of the innate immune system with its characteristic signals of fever, blood pressure and other signs ranging from flu-like symptoms to septic shock.

Ocular and oral symptoms are among the most important “survival” traits of the species. A significant amount of cortical memory is allotted to the discrimination of “painful” stimuli, and learning to avoid such stimuli is highly refined.

At the one end of the spectrum, we still have not really understood at a molecular basis why we feel like we have been hit by a truck after a viral flu, or why we are tired and cognitively slow after a long airplane flight that we call “jet lag.”

Flecks of reddish-purple discoloration are seen in the lower portion of the cornea and conjunctiva. These changes are typical of keratoconjunctivitis sicca when the eye is stained with Rose Bengal dye; they are the result of decreased tear formation and represent corneal abrasions. Corneal abrasions may be prevented by the use of artificial tears.

Image Source: Rheumatology image library

No one would accuse a symptomatic “normal” individual of malingering if these symptoms were present, but would attribute them to some disruption of neurokines by the virus (or the innate response to it) or to a readjustment of neurokines to our circadian internal clocks in the case of jet lag.

The fascinating extreme of dysfunction is “phantom pain,” as shown by Ramachandran et al, where an amputated limb “hurts.”5 This is explained at the level of brain processing (and its descending afferents) through a network called “veto neurons.” Roughly, the brain processes a variety of inputs, and the absence of a signal (such as pain or position fibers from a missing limb) is important information to the cortical memory bank. The silencing of these “nociceptive” signals is performed normally by other neurons in the brain.

An even more fascinating observation by functional magnetic resonance imaging is that these processes show up by objective (although still crude) scanning techniques.

There must be a transition of Ramachandran’s (and other behavioral psychologists’) observations from the level of the “integrative or mystic” practitioner to rheumatology with predictable hypotheses, reproducible methods of documentation and subsequent clinical recommendations.

For a fascinating glimpse into this new world of the neurobiology of pain and behavior (at least new to this rheumatologist), there are a large number of published articles5-8 on this, as well as available TED talks or YouTube presentations by neurologist Vilayanur Ramachandran and co-workers at University of California San Diego and Salk Institute.

It would be a worthwhile and enjoyable investment of a few minutes to appreciate the advances in neuroscience that have been revealed by functional MRI and elucidation of genetic mutations governing neuronal synaptic conductivity that influence our sensations of pain.

From Genes to Therapy: Why Have We Made So Little Progress?

We have correctly spent the past 30 years identifying the contributing genes, their epigenetic modifications and trying different therapies to block their end effect. This approach was incredibly successful in stumbling onto TNF and then other pathways in RA.

Rheumatologists need to keep our fingers on the pulse of neurologic and psychological research, since these complaints of dry eyes and dry mouth are present not only in SS, but also in depression, demyelinating diseases and aging.

Neurologic manifestations (from painful neuropathies to loss of executive function) now have rheumatologists trembling during our abbreviated time allotted for a patient revisit … and I am not sure that we have made a lot of progress with the problems that brought patients to the rheumatology clinic with a diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome a generation ago.

As cognizant human beings, we only know what our brain tells us is painful, and this is a learned response.

Summary

It has been a fascinating decade, and we have to warmly remember a generation of talented and dedicated researchers who established the clinical and laboratory basic guidelines of patient care for SS.

The past generation of immunology researchers has unveiled the beauty of the innate immune system as it “talks” to the “acquired” immune system.

Nevertheless, we have to recognize the overall umbrella of the “danger hypothesis” originally described by Matzinger and others that gave rise to not only recognition of these immune responses, but also the neuro-endocrine responses first recognized in the adrenocortical axis by Hans Selye more than 60 years ago.9 Our fascination with cytokine loops in rheumatology has led to our ignoring other molecular mechanisms that mediate the relation of “danger” or “stress signals” to sickness behavior.

It is correct in science to believe that it is only “true” if we can verifiably measure it … though we should avoid the arrogance that we are capable of measuring all the variables that form the molecular basis of pain or behavior, namely, the “software” of the brain.

SS sits at the interface of neurology, immunology and behavioral science. These patients can be defined at least phenotypically as counterparts and represent a good starting point for the next decade of imaginative research.

Robert I. Fox, MD, PhD, is chief of the Rheumatology Clinic at Scripps Memorial Hospital–Ximed in La Jolla, Calif.

Carla M. Fox, RN, is a registered nurse in the clinic at Scripps Memorial Hospital–Ximed.

References

- Bloch KJ, Buchanan WW, Wohl MJ, et al. Sjögren’s syndrome: A clinical, pathological and serological study of 62 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1956;44:187–231.

- Mekinian A, Ravaud P, Hatron P, et al. Efficacy of rituximab in primary Sjögren’s syndrome with peripheral nervous system involvement: Results from the AIR registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Jan;71(1):84–87.

- St. Clair EW, Levesque MC, Prak ET, et al. Rituximab therapy for primary Sjögren’s syndrome: An open-label clinical trial and mechanistic analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Apr;65(4):1097–1106.

- Devauchelle-Pensec V, Mariette X, Jousse-Joulin S, et al. Treatment of primary Sjögren syndrome with rituximab: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Feb 18;160(4):233–242.

- Ramachandran VS, Blakeslee S, Sacks OW. Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind. New York: William Morrow, 1998.

- Ramachandran VS. Filling in gaps in perception: Part II. Scotomas and phantom limbs. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 1993 Apr;2:56–65.

- Ramachandran VS, Rogers-Ramachandran D. Phantom limbs and neural plasticity. Arch Neurol. 2000 Mar;57(3):317–320.

- Armel KC, Ramachandran VS. Projecting sensations to external objects: Evidence from skin conductance response. Proc Biol Sci. 2003 Jul 22; 270(1523):1499–1506.

- Matzinger P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:991–1045.