BALTIMORE—At the 20th Annual Advances in the Diagnosis and Treatment of the Rheumatic Diseases symposium at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Jun Kang, MD, assistant professor of dermatology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, regaled the audience with his talk, Dermatology and Rheumatic Disease. He discussed a stepwise approach to evaluating skin lesions and helping patients receive proper diagnoses and treatments.

BALTIMORE—At the 20th Annual Advances in the Diagnosis and Treatment of the Rheumatic Diseases symposium at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Jun Kang, MD, assistant professor of dermatology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, regaled the audience with his talk, Dermatology and Rheumatic Disease. He discussed a stepwise approach to evaluating skin lesions and helping patients receive proper diagnoses and treatments.

Assessment

Dr. Kang began by discussing primary lesion morphology analysis, a method for describing and categorizing skin lesions based on their shape, size, color and other characteristics. Dermatologists routinely employ this technique and rely on heuristics to quickly arrive at a diagnosis. However, for rheumatic diseases, such shortcuts may be less reliable. A clinician is more likely to arrive at the correct diagnosis if they have seen the presentation before and if they understand how to correlate the histologic findings on skin biopsy with the patient’s clinical course.

Dr. Kang noted that patients may require multiple skin biopsies for diagnosis because inflammatory skin diseases can have overlapping clinical and histologic findings, with nuanced variations. The timing and location of biopsy may also influence the interpretation of the results. Although clinicians generally believe in searching for a unifying diagnosis, one must be aware of Hickam’s dictum, which states that patients “can have as many diseases as they damn well please.”1

CLE

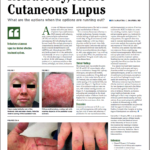

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) may be: 1) acute, commonly presenting with a malar rash; 2) subacute, which often manifests with a scaly, red, raised, non-scarring rash in sun-exposed areas; or 3) chronic, such as discoid lupus, lupus panniculitis or chilblain lupus.

The majority of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (70–85%) have skin involvement over the course of their disease. Skin involvement is the presenting sign of disease in 25% of cases.2

In Dr. Kang’s view, essentially all patients with acute CLE have SLE. He explained that skin lesions can sometimes be challenging to recognize in lupus because early scalp discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) can mimic the pre-scarring phase of alopecia areata and the histologic progression of chronic CLE can mimic morphea. The detection of interface dermatitis on biopsy can be helpful because nearly all forms of CLE are unified by this finding, with the exceptions of tumid lupus and lupus profundus/panniculitis. However, interface dermatitis is not unique to lupus and can be seen in dermatomyositis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), erythema multiforme, graft-vs.-host disease, mycosis fungoides and other conditions.