A new study suggests that oils on the skin surface represent a mechanism of barrier immunity by acting as natural, tissue-specific autoantigens. The newly discovered antigenic property of skin oil also suggests a mechanism behind how alterations in lipid content may influence disease. Annemieke de Jong, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues published their identification of a novel class of autoantigens online Dec. 22 in Nature Immunology.1

Antigens are typically considered to be peptides or proteins that are positioned within MHC molecules or grooves in CD1. The antigens rise up from the groove and make contact with the T cell receptor (TCR). Because of this understanding of peptide antigens, studies of autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis, have focused primarily on protein autoantigens and their interactions with CD1 and TCR.

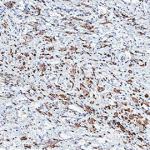

Researchers have demonstrated that autoimmunity can result from CD1 proteins bound to self-molecules or to CD1a itself. De Jong and colleagues began their study by investigating this distinction. They used an experimental system (K562 human myelogenous leukemia cells transfected to express CD1 molecules) that allowed them to measure the autoreactivity of T cells to CD1a, CD1b, CD1c, and CD1d. They found that CD1-autoreactive T cells show only baseline reactivity when autoantigens are present on the antigen presenting cells (APCs). The investigators then leveraged the system and produced recombinant CD1a proteins that were able to activate T cells, thus creating an APC-free system for identifying antigens.

The authors then proceeded to unload ligands from CD1a by reducing the pH to 6.5-4, a level that does not cause irreversible unfolding of CD1a proteins. They went on to identify lipid antigens, squalene and wax esters, as relatively potent natural CD1a autoantigens. The lipid autoantigens are distinct from protein autoantigens, however, in that they do not have the chemical basis for hydrogen bonding or charge-charge interactions with the TCR.

The discovery of lipid antigens is not completely surprising. Immunologists have long known that lipids found in poison ivy and incomplete Freund’s adjuvant can cause an immune response. The new study demonstrates, however, that lipid molecules are recognized by T cells. They appear to be recognized because they create a non-interference with an interaction between CD1a and the TCR.

Thus, skin oils seem to act as headless mini-antigens that nestle within CD1a, displacing non-antigenic resident lipids that have large head groups. In this way, the diverse oily substances are able to generate specific immune responses.

“These results identify natural lipids present in the skin that augment and inhibit human T cell response, further supporting the idea that lipids are T cell antigens. More practically, this study by Annemieke de Jong, identifies ceramides, which are common components of therapeutic skin creams, as inhibitors of human T cells,” wrote lead investigator D. Branch Moody, MD, also of Harvard Medical School in an e-mail to The Rheumatologist.

Specifically, the authors propose that either: 1) the apolar squalene antigens stabilizes the CD1a groove or 2) they displace inhibitory ligands. The two theories are not mutually exclusive. Either way, the results suggest that oils in skin creams may be able to modify intradermal immune responses.

“The lipid antigens identified here are in sebum. We hypothesize that when oils that are normally on the skin surface are pushed down into deep layers by inflammation or abrasion of the skin, this is molecular signal that identifies skin breach,” wrote Dr. Moody.

Lara C. Pullen, PhD, is a medical writer based in the Chicago area.