Small fiber neuropathy is a common form of peripheral neuropathy with multiple potential etiologies and a varied clinical presentation. It can’t be detected by nerve conduction studies, making it an elusive and often overlooked entity. Small fiber neuropathy is well documented in several rheumatic diseases, and its symptom burden can profoundly affect quality of life. Thus, rheumatologists should have the knowledge to suspect and evaluate for this condition in the clinic.1

Small fiber neuropathy is a common form of peripheral neuropathy with multiple potential etiologies and a varied clinical presentation. It can’t be detected by nerve conduction studies, making it an elusive and often overlooked entity. Small fiber neuropathy is well documented in several rheumatic diseases, and its symptom burden can profoundly affect quality of life. Thus, rheumatologists should have the knowledge to suspect and evaluate for this condition in the clinic.1

In this article, we speak with Michael Polydefkis, MD, associate professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, where he collaborates with the Jerome L. Greene Sjögren’s Syndrome Center and has a particular interest in peripheral neuropathy. His expertise is in nerve conduction studies, electromyography, and nerve, skin and muscle biopsy. He shares his practical approach to the diagnosis and management of small fiber neuropathy with an emphasis on essential knowledge for both the community and academic rheumatologist.

Background

Peripheral nerve fibers can be broadly classified by nerve fiber diameter as small or large. Small fiber neuropathy is due to the destruction of the smaller, lightly myelinated A-delta and unmyelinated C fibers.2 Small fibers, the largest subset of peripheral nerves, include nociceptors and autonomic fibers. Damage to these often results in positive symptoms, such as pain, paresthesia (i.e., a burning or prickling sensation) and allodynia (i.e., extreme sensitivity to touch; pain due to a stimulus that does not normally provoke pain).

Large fibers, on the other hand, represent a smaller subset of peripheral nerves and, when dysfunctional, lead to negative symptoms, such as loss of proprioception and vibration sense, diminished ankle reflexes and numbness. Dr. Polydefkis points out that “large fibers also innervate muscles and, therefore, can be associated with weakness when injured.”

Most neuropathies, such as diabetic neuropathy, involve dysfunction of both small and large fibers. Dr. Polydefkis says “in many instances, small fibers are affected first, and patients then develop large fiber involvement with time,” as occurs in diabetes.

Length dependence is an essential concept to be cognizant of when evaluating for neuropathy. When a neuropathy presents in a length-dependent manner, it first appears in the nerves of the greatest length, such as at the toes, and then progresses proximally up the lower extremities, with eventual involvement of the hands and upper extremities. This is the classic pattern of a diabetic- or alcohol-related neuropathy. Small fiber neuropathy, however, can be non-length dependent,and proximal regions may be affected first, with patchy involvement that does not map onto a particular sensory nerve distribution.2

Presentation

“Patients with small fiber neuropathy classically complain of burning and stinging dysesthesia in the feet that is worse at night and aggravated by prolonged standing or walking,” says Dr. Polydefkis. The onset is indolent, symmetric and painful, and is most commonly length dependent.

Dr. Polydefkis

He would expect a patient with an isolated small fiber neuropathy to have normal strength, normal reflexes and normal vibration thresholds. “If any of these are abnormal, this is likely not a small fiber neuropathy,” he says.

Given small fiber regulation of autonomic function, patients may also present with changes in sweating, urination and bowel function.

Evaluation

Evaluation for suspected small fiber neuropathy consists of a thorough history, examination and diagnostic testing. Small fiber neuropathy is idiopathic in 50% of cases, but most commonly is due to diabetes mellitus.3 Dr. Polydefkis recommends evaluating for vascular risk factors, such as diabetes, hypercholesterolemia and hypertension, nutritional deficiencies and other metabolic causes, such as hypothyroidism and cancer. Toxic exposures, such as chemotherapy, excess pyridoxine and immune modulators, are also common causes, and if a family history of neuropathy exists, inherited causes should be considered.

Among the rheumatic etiologies, small fiber neuropathy is most commonly seen in Sjögren’s disease, and has also been demonstrated in sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and scleroderma. In patients with Sjögren’s disease, neurologic symptoms may precede the diagnosis of Sjögren’s. Notably, Sjögren’s disease is associated with several disorders of the peripheral nervous system, and small fiber neuropathy is among the most common. Patients with small fiber neuropathy and Sjögren’s are more commonly seronegative and, thus, lack anti-SSA and anti-SSB autoantibodies.4

In several studies, small fiber neuropathy has also been demonstrated in patients with fibromyalgia.5 “This is an evolving area,” says Dr. Polydefkis, and “those studies tended to have small sample sizes. Further work is needed.”

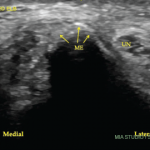

Diagnostic testing for peripheral neuropathy often begins with a nerve conduction study. However, in small fiber neuropathy, nerve conduction study results will be normal given that the lightly and unmyelinated small nerve fibers result in conduction beyond the resolution of the test.2 Diagnostic confirmation requires a cutaneous nerve biopsy, performed via a punch biopsy. The specimen is examined for intra-epidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD), which is considered abnormal when reduced, particularly when less than the fifth percentile.3

In practice, Dr. Polydefkis often performs skin biopsies at “proximal and distal sites along the leg. Standard sites have been established and normative values have been published. Because most forms of peripheral neuropathy affect the distal terminals of the longest nerve fibers, the distal leg site is the most sensitive to detect small fiber neuropathy.” In non-length-dependent small fiber neuropathy, the intraepidermal nerve fiber density may be abnormal in skin from proximal sites with normal distal biopsy findings.

Skin biopsy should be avoided when the source of neuropathy is already clear, such as in a mixed fiber neuropathy or when there are symptoms beyond those attributable to small fiber neuropathy, such as loss of deep tendon reflexes or weakness.3

Management

Management of small fiber neuropathy focuses on symptomatic control of neuropathic pain, primarily with antidepressants, anti-epileptics and sometimes opiates. “Among antidepressants, tricyclic and [serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors] have demonstrated efficacy while [selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors] have not,” says Dr. Polydefkis. “Among antiepileptics, gabapentin and pregabalin are generally preferred over carbamazepine, lamotrigine or phenytoin, which have shown efficacy but require monitoring or have high rates of adverse events. Tramadol can be helpful in patients who tolerate sporadic treatment. The agent or combination of agents selected is based on a patient’s concomitant medical issues.”

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) “is not an accepted symptomatic treatment for small fiber neuropathy,” he says, but it may be used in rheumatic conditions associated with small fiber neuropathy. In a double-blind, randomized controlled study of patients with idiopathic small fiber neuropathy, Geerts et al. demonstrated no clinically relevant benefit of IVIG, which was not only expensive, but had risk of adverse events.6 However, case reports and small series have demonstrated success with IVIG in Sjögren’s disease-related small fiber neuropathy.7

In Sum

Rheumatologists should be familiar with small fiber neuropathy, particularly in patients with underlying Sjögren’s disease. Definitive diagnosis requires a cutaneous nerve biopsy. Management primarily involves relieving neuropathic pain through various medications, with an approach tailored to the patient. Data on the role of immunosuppression in small fiber neuropathy are limited.

Michael Cammarata, MD, is a second-year rheumatology fellow at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore.

Michael Cammarata, MD, is a second-year rheumatology fellow at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore.

References

- Seeliger T, Dreyer HN, Siemer JM, et al. Clinical and paraclinical features of small fiber neuropathy in Sjögren’s syndrome. J Neurol. 2023 Feb;270(2):1004–1010.

- Terkelsen AJ, Karlsson P, Lauria G, et al. The diagnostic challenge of small fibre neuropathy: Clinical presentations, evaluations, and causes [published correction appears in Lancet Neurol. 2017 Dec;16(12):954]. Lancet Neurol. 2017 Nov;16(11):934–944.

- Saperstein DS. Small fiber neuropathy. Neurol Clin. 2020 Aug;38(3):607–618.

- McCoy SS, Baer AN. Neurological complications of Sjögren’s syndrome: Diagnosis and management. Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol. 2017 Dec;3(4):275–288.

- Bailly F. The challenge of differentiating fibromyalgia from small-fiber neuropathy in clinical practice. Joint Bone Spine. 2021 Dec;88(6):105232.

- Gibbons CH, Klein C. IVIG and small fiber neuropathy: The ongoing search for evidence. Neurology. 2021 May 18;96(20):929–930.

- Rist S, Sellam J, Hachulla E, et al. Experience of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in neuropathy associated with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A national multicentric retrospective study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011 Sep;63(9):1339–1344.