As medicine enters an era of patient-centered care, patient satisfaction has become an increasingly important gauge of physician performance. Nearly a billion dollars in Medicare reimbursement to hospitals during the past 12 months depended on patient satisfaction scores, assessed through a survey instrument known as HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Hospital Providers and Systems). Outpatient practices are also increasingly measuring satisfaction with caregivers. The most widely used instrument for medical systems to independently measure patient satisfaction has been marketed by a company known as Press Ganey (South Bend, Ind.). Proponents argue that improved satisfaction is a means to better the health of our nation. With this growing focus, close scrutiny of this metric is warranted. I can illustrate my personal perspective by describing two colleagues.

Physician 1

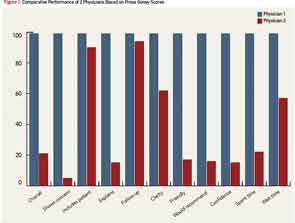

Physician 1 is a rheumatologist and chief of his division at an academic institution. He is a senior physician who has been plying his trade for almost 40 years, and he takes a great deal of pride in the care that he provides. He has some special incentives. His father’s autobiography became a popular movie that describes how a physician feels when he becomes a patient.1 Physician 1 has nine close relatives who are physicians, including his wife, two daughters and two of his brothers. One of his daughters has achieved some notoriety for her writing on patient-centered issues, such as satisfaction, physician duty hours and shared decision making.2,3,4 These themes have apparently motivated Physician 1 appropriately, because his satisfaction ratings are outstanding (see Figure 1). He is at the 99th percentile in all 12 Press Ganey categories, including overall approval.

Physician 2

Based on Press Ganey scores, Physician 2 is not nearly so skilled. Physician 2 also practices at an academic institution where he, too, is quite senior. Nearly 30 years ago, he established an interdisciplinary ophthalmology clinic to care for patients with complicated problems related to inflammation in and around the eye. The physician and the clinic have enjoyed success. His peers honored him by electing him president of the American Uveitis Society. Some patients drive nearly a thousand miles to attend the clinic. No fewer than five trainees, including four board-certified or board-eligible ophthalmologists, assist in the clinic because of the unique learning experience. And visiting faculty have come from all over the world, including Korea, India, China, Japan, Norway, England and Canada, to observe how the clinic functions. But patients completing a Press Ganey survey give Physician 2 marks that are well below average (see Figure). On 8 of 12 scales, he rates below the 25th percentile, and his overall rating is at the 22nd percentile.

What’s the Difference?

What does Physician 2 need to learn? Patient satisfaction can be markedly affected by such amenities as the availability of convenient parking or the ambiance in the waiting room. It is unlikely that parking, the architecture of his office building or the magazines in the waiting area explain the substandard scores, because Physician 2 is fortunate to practice in a modern facility designed by an internationally recognized architect, with parking conveniently located in an adjacent structure, and Physician 1 has less elegant surroundings. Is Physician 2 guilty of something that could be remedied, such as the wrong deodorant, poor choice of ties or a haughty demeanor? Or perhaps his satisfaction rating is reflecting the subconscious response of patients to race, gender, religion, age, height or sexual preference, aspects of Physician 2 that cannot and should not be “remedied.”