As medicine enters an era of patient-centered care, patient satisfaction has become an increasingly important gauge of physician performance. Nearly a billion dollars in Medicare reimbursement to hospitals during the past 12 months depended on patient satisfaction scores, assessed through a survey instrument known as HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Hospital Providers and Systems). Outpatient practices are also increasingly measuring satisfaction with caregivers. The most widely used instrument for medical systems to independently measure patient satisfaction has been marketed by a company known as Press Ganey (South Bend, Ind.). Proponents argue that improved satisfaction is a means to better the health of our nation. With this growing focus, close scrutiny of this metric is warranted. I can illustrate my personal perspective by describing two colleagues.

Physician 1

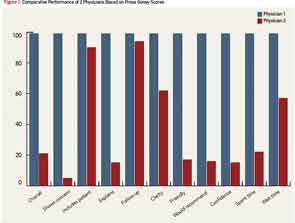

Physician 1 is a rheumatologist and chief of his division at an academic institution. He is a senior physician who has been plying his trade for almost 40 years, and he takes a great deal of pride in the care that he provides. He has some special incentives. His father’s autobiography became a popular movie that describes how a physician feels when he becomes a patient.1 Physician 1 has nine close relatives who are physicians, including his wife, two daughters and two of his brothers. One of his daughters has achieved some notoriety for her writing on patient-centered issues, such as satisfaction, physician duty hours and shared decision making.2,3,4 These themes have apparently motivated Physician 1 appropriately, because his satisfaction ratings are outstanding (see Figure 1). He is at the 99th percentile in all 12 Press Ganey categories, including overall approval.

Physician 2

Based on Press Ganey scores, Physician 2 is not nearly so skilled. Physician 2 also practices at an academic institution where he, too, is quite senior. Nearly 30 years ago, he established an interdisciplinary ophthalmology clinic to care for patients with complicated problems related to inflammation in and around the eye. The physician and the clinic have enjoyed success. His peers honored him by electing him president of the American Uveitis Society. Some patients drive nearly a thousand miles to attend the clinic. No fewer than five trainees, including four board-certified or board-eligible ophthalmologists, assist in the clinic because of the unique learning experience. And visiting faculty have come from all over the world, including Korea, India, China, Japan, Norway, England and Canada, to observe how the clinic functions. But patients completing a Press Ganey survey give Physician 2 marks that are well below average (see Figure). On 8 of 12 scales, he rates below the 25th percentile, and his overall rating is at the 22nd percentile.

What’s the Difference?

What does Physician 2 need to learn? Patient satisfaction can be markedly affected by such amenities as the availability of convenient parking or the ambiance in the waiting room. It is unlikely that parking, the architecture of his office building or the magazines in the waiting area explain the substandard scores, because Physician 2 is fortunate to practice in a modern facility designed by an internationally recognized architect, with parking conveniently located in an adjacent structure, and Physician 1 has less elegant surroundings. Is Physician 2 guilty of something that could be remedied, such as the wrong deodorant, poor choice of ties or a haughty demeanor? Or perhaps his satisfaction rating is reflecting the subconscious response of patients to race, gender, religion, age, height or sexual preference, aspects of Physician 2 that cannot and should not be “remedied.”

An astute reader might have surmised that I am Physician 1. An even more astute reader might have deduced that I am also Physician 2. How can one provider be scored so divergently?

Representatives from Press Ganey would probably argue that the relatively small number of surveys—eight for the rheumatology clinic and 11 for the ophthalmology clinic—mean the differences might not be statistically significant. The report, unfortunately, does not provide standard deviations to allow a statistical comparison. Further, studies based on Press Ganey have been published in peer-reviewed journals with response rates to the survey instrument as low as 7.5%.5 By relying on the responses from a minority of those contacted, the ratings are skewed unpredictably based on who is motivated to complete a survey. In addition, the U.S. government does not care about statistical significance. In distributing payment based on HCAHPS, what matters is whether the institution rates above or below the 50th percentile even if the difference between 50th percentile and 5th percentile is not statistically significant.

Unlike the citizens who are uniformly above average in Garrison Keillor’s fabled Lake Wobegon, all hospitals are not above average. For one three-month stretch, my rheumatology division received an overall Press Ganey rating of nearly 90% and was below the magical 50th percentile. Another quarter, our ratings minimally changed to 92%, a barely perceptible improvement, but the 2 or 3% change in absolute rank made a 44% change in percentile, placing us at the 92nd percentile.

Another possible explanation for the discrepant scores is the effect of residents and fellows in the clinic of Physician 2. A study from Duke, for example, found that residents receive slightly lower satisfaction ratings from patients compared with attending physicians.6 (Intriguingly another study found no correlation between the satisfaction of patients with a medical resident and the attending physician’s assessment of the resident’s skills).7 I am not aware of data to indicate that residents reduce the rating of a faculty member. However, based on recent HCAHPS data, teaching hospitals are less likely than nonteaching hospitals to receive an unqualified, positive recommendation from patients (http://www.hcahpsonline.org/Files/Chart_book_data_2013_1_April_V3._Merged.pdf).

Unpublished data from my university’s rheumatology clinic also show that the patient’s diagnosis influences satisfaction. Patients with fibromyalgia, for example, are significantly less satisfied with their care compared with the rating from all patients.

Although these observations might explain why my care is perceived differently in two separate clinics, the potential effects of trainees and underlying disease provide additional reasons to be dissatisfied with satisfaction as a measure of quality.

Practicing Medicine Should Not Be a Popularity Contest

What is the solution? Like virtually every physician, I want my patients to like and appreciate me. But practicing medicine should not be a popularity contest.

Discouraging the inappropriate use of antibiotics, naturopathic remedies, narcotics and MRIs might be excellent advice, but these same recommendations might conflict with the patient’s preconceived goals and, thus, result in reduced satisfaction. In 2001, Kendrick and colleagues published a landmark study on the effects of randomly obtaining X-rays to evaluate patients with low back pain.8 The study involved more than 400 subjects. Eighty percent of subjects wanted an X-ray, and those who received an X-ray were more satisfied with their care after nine months. But those who received an X-ray also experienced more severe pain, a longer duration of pain and more disability. They also had more visits to a physician. Satisfaction was, thus, inversely related to outcome.

Fenton and colleagues reached a similar, but even more disturbing, conclusion in their 2012 publication that followed a large cohort of patients over time, collecting data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.9 Those who were most satisfied with their doctor were also most likely to die.

To be sure, some studies describe positive effects from patient satisfaction. For example, Glickman and colleagues found that patients who were more satisfied with their care for an acute myocardial infarction were less likely to die as an inpatient.10 But this same study found that nurses were the most influential factor in determining satisfaction. Interestingly, satisfaction with visiting hours was also an important parameter that correlated with overall satisfaction.

Practicing medicine should not be a popularity contest. Our role as caregivers is to protect the health of our patients.

One of the worst aspects of using satisfaction as a measure of quality is its effect on physician morale. There’s an old joke: What do you call the student who graduates last in the medical school class? Answer: a doctor. The joke requires an update. What do you call 417,000 physicians in the U.S.? Answer: substandard, because they represent the number below the 50th percentile in patient satisfaction.

Personally, if I had seen my ophthalmology scores only, I would have spent months pondering the reasons for this failing grade. The rheumatology scores helped me appreciate how flawed the measurements are.

One suggestion is that scores should not be scaled by percentile. A physician with a 90% approval rating should be pleased, just as a restaurant, grocery store, airline or cobbler would be pleased. But for physicians, 90% approval may well fall below the 50th percentile. This is grossly unfair.

Patient-Centered Practice

I do not favor abandoning patient satisfaction completely as a metric for care. Our role as caregivers is to protect the health of our patients. Knowing that patient satisfaction will be assessed serves to remind us of this patient-centered mission. But if the motivation to measure satisfaction is to provide better care, what is the motivation to provide a better metric?

James T. Rosenbaum, MD, is professor of ophthalmology, medicine and cell biology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, Ore., and chief of ophthalmology at Legacy Devers Eye Institute, also in Portland.

Acknowledgments: The author is grateful for financial support from the William and Mary Bauman Foundation, the Stan and Madelle Rosenfeld Family Trust, and Research to Prevent Blindness. The author is grateful to Lisa S. Rosenbaum for constructive comments regarding the content of this essay.

References

- Rosenbaum EE. The Doctor. Random House, New York, 1988.

- Rosenbaum LS. The down side of doctors who feel your pain. The New York Times. Oct. 31, 2011.

- Rosenbaum LS, Lamas D. Residents’ duty hours—toward an empirical narrative. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2044–2049.

- Rosenbaum LS. How should doctors share impossible decisions with their patients? The New Yorker (online edition), July 5, 2013.

- Guss DA, Leland H, Castillo EM. The impact of post-discharge patient call back on patient satisfaction in two academic emergency departments. J Emerg Med. 2013;44:236–241.

- Yancy WS Jr., Macpherson DS, Hanusa BH, et al. Patient satisfaction in resident and attending ambulatory care clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):755–762.

- Resnick AS, Disbot M, Wurster A, et al. Contributions of surgical residents to patient satisfaction: Impact of residents beyond clinical care. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(3):243–252.

- Kendrick D, Fielding K, Bentley E, et al. Radiography of the lumbar spine in primary care patients with low back pain: Randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322:400–405.

- Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, et al. The cost of satisfaction: A national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Int Med. 2012;172:405–411.

- Glickman SW, Boulding W, Manary M, et al. Patient satisfaction and its relationship with clinical quality and inpatient mortality in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:1.