Rheumatologists treat more than 100 autoimmune diseases, and most agree that scleroderma is the worst. It disfigures patients and, in doing so, restricts bodily functions and social interactions. It also kills.

Rheumatologists treat more than 100 autoimmune diseases, and most agree that scleroderma is the worst. It disfigures patients and, in doing so, restricts bodily functions and social interactions. It also kills.

In January, Keith M. Sullivan, MD, professor of medicine at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., and colleagues reported in the New England Journal of Medicine that myeloablative autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation resulted in long-term benefits for patients with severe scleroderma.1

Patients in the trial, Scleroderma: Cyclophosphamide or Transplantation (SCOT), experienced improved event-free and overall survival. The study randomized patients to receive either stem cell therapy or cyclophosphamide treatment, and demonstrated that patients in the stem cell therapy group had increased cytopenias, but significantly better six-year survival after transplant (86% vs. 51%). The rates of treatment-related death and post-transplantation use of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) were lower than previous studies of nonmyeloablative transplantation.

Inform Patients of the Treatment Option

Dr. Sullivan spoke with The Rheumatologist about the results of the SCOT trial and urged rheumatologists to refer patients with scleroderma and internal organ involvement to a transplant center for consultation. Scleroderma is a rare disease, and diagnosis may be difficult or delayed. “Without an early referral, patients really won’t understand the details of the procedure, the risks and the gains,” he explains.

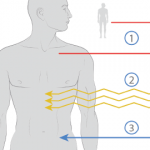

Patients whose scleroderma is limited to their skin typically do not experience an increase in mortality. However, one-third of the roughly 300,000 patients with scleroderma in the U.S. experience internal organ involvement, primarily of the lungs, kidneys and/or heart. These patients often progress to organ failure and death. Dr. Sullivan and colleagues are particularly interested in this subset of patients and think the benefits of stem cell treatment outweigh its risks for these patients. Dr. Sullivan suggests rheumatologists identify these patients early in disease via serial pulmonary function testing and CT chest imaging.

A Six-Year Study

The SCOT trial enrolled patients with severe scleroderma who had severe internal organ disease (as opposed to solely skin disease) and treated them with myeloablative therapy followed by CD34+ selected autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The publication of this research joins two other positive studies, one published in Lancet and the other published in JAMA, that tested nonmyeloablative transplant vs. cyclophosphamide.2,3

“This [research] has been a long-term investment for all my colleagues and NIH,” explains Dr. Sullivan. He emphasizes that the SCOT trial followed all participants for six years, during which the NIH award paid for patients to travel frequently back to their transplant center for assessments, monthly for a year then quarterly through Year 5. The trial demonstrated the durability of the beneficial effects of the stem cell treatment.