At some point, Josh stopped coming to the office. He didn’t refill his prescriptions. We called his cell phone; no answer. I wondered if he’d moved or committed suicide, or overdosed. We never had been able to titrate the hydrocodone down. His burden of pain was real; between his end-stage knees and painful back, it seemed appropriate for Josh to be treated with narcotics. But I had my concerns. I checked the obituaries in the paper. Joanne finally tracked down Josh’s mother who was back living in northern Maine. I called her.

“Josh is in jail,” she said. “Dealing drugs. They got him, and now he’s in Thomaston.” There was a long pause. “I can only hope they give him a break. That boy has suffered enough.”

I made a few calls. Through the prison system, Josh was getting a reasonable alternative to the intravenous infliximab, etanercept, which could be administered as an injection. I spoke to the doctor in charge, who reassured me that Josh was getting good care.

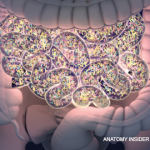

As the months and then years flowed by, I often thought of Josh and wondered if he’d ever had his knees replaced. I never did aspirate more fluid from a diseased knee. Josh’s aspirate of 300 cc remained a dubious record. At our weekly rheumatology conferences, Josh’s name would come up, as in, “This patient has very active disease, but not as severe as Josh N.’s ankylosing spondylitis.” The other rheumatologists would nod their heads and agree. No, Josh was the worst. The absolute worst. Whatever happened to him?

Then one day, Josh came in for an office visit. By now, he was in his mid-20s and had suffered with AS for 12 years. I watched as Joanne guided him down the hallway to the scale. Inside the exam room, he told me that his five years in prison was not altogether wasted. He’d gotten his GRE and learned a trade. A local vegetarian restaurant had recently hired him as a line cook. I watched Josh arrange himself in the exam chair—one pillow behind his back and the other under his butt. The T-shirt had been replaced by a loose-fitting, floral bowling shirt. My eyes scanned down to the front pocket: No cigarettes. Good. On his feet he wore bowling shoes with a Velcro strap closure. Very classy.

Pulling up a pant leg, he showed me the vertical scar of matching knee replacements. Beneath his shirt, he wore a soft Velcro back brace, which helped, he said, but most of the time he just put the pain aside and tried to stay busy.