AS, unlike rheumatoid arthritis, undeniably goes back thousands of years and afflicts crocodiles, as well as humans.1 Although nearly all rheumatologic conditions are more common in women than men, AS, at least in its most severe forms, occurs more frequently in men.2 We know that the gene coding for the Class 1 MHC molecule, HLA‑B27, is found in more than 90% of Caucasians with AS, and that bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract in some poorly defined way, play a role in the pathogenesis of this disorder.

Rheumatologists have known for decades that patients who are HLA‑B27+ may develop reactive arthritis after GI infections due to Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella or Yersinia.3 After exposure, there is a delay of one or two weeks before an explosive large joint polyarthritis occurs (sometimes with axial spine and sacroiliac involvement). The joints themselves are not infected, but are the target of an immunologic storm of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In time, however, reactive arthritis usually resolves.

But what of AS? How important are bacteria in the pathogenesis of this more insidious and chronic disease? The clues are coming from both basic science and clinical research, but as yet there is not a comprehensive explanation for how we get from the Class I HLA-B27 cell surface molecule to inflamed joints, from a normal spine to a bamboo spine. How do we explain Joshua N or Michael T?

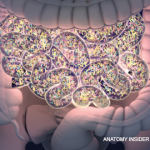

Clarifying the triggers for AS has been elusive, in part due to the complex immunology of the gut. We know that billions of bacteria coexist with us in the gut, but until recently, exactly what they were doing there was a complete mystery. Basic science is beginning to unravel the complex ecology of the gut, which should lead to a clearer understanding of how our own native bacteria affect health.

Scientists can now transfect an attenuated virus (a virus incapable of causing disease), and insert the human HLA-B27 gene into the virus’s genetic code. When the virus is injected into a mouse, copies of the human HLA-B27 markers can subsequently be detected on the cell surface of the mouse’s cells. What happens next to these previously normal mice? They develop diarrhea, inflammation in the bowel and skin, and after a delay of a week or so, inflammation in the joints. This study raises the question: Are the mice’s own native bacteria interacting with the human HLA-B27 gene and triggering arthritis in distant joints?4