For the last six months, the rheumatology research community has been buzzing about the “American Recovery and Reinvestment Act” (ARRA), a stimulus package signed into law by President Barak Obama in February that has injected billions into federally funded research grant programs. The extra dollars are a welcome boost to a tight funding environment, but several aspects of the stimulus package funds make the ARRA grants a unique mix of challenge and opportunity.

Infusion of Dollars

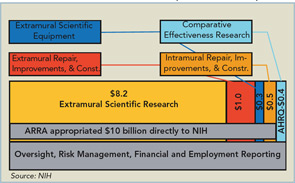

The ARRA stimulus program injected approximately $10 billion into the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Of this, around $8.2 billion was appropriated for extramural scientific research. The rest was to be spent on various items such as repair, renovation, or construction—both within and outside of the NIH—comparative effectiveness research through the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ), and extramural equipment purchases (See Figure 1, p. 33).

“The big chunk of money went to scientific research, and each institute and center was allowed to develop their own funding priorities,” says Robert Carter, MD, deputy director of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS). “We wanted the community to tell us their needs. We asked, within constraints given us by Congress, for proposals the researchers thought were worthy.”

The ARRA legislation had some additional considerations that were not part of the usual NIH Requests for Application (RFA). Chief among these was a requirement that the money be allocated and spent within two years. In addition, there was an obligation to either save or create jobs for economic benefit.

NIAMS was looking for proposals that would really open doors and use the money in ways different from business as usual. We wanted to ask new questions that otherwise wouldn’t be possible.

—Robert Carter, MD

“The NIAMS portion of ARRA is approximately the equivalent, in terms of dollars, to the amount of new research grants NIAMS will fund through the normal appropriation this year, a once-in-a-lifetime bolus of money,” says Dr. Carter. “We wanted to take advantage of this unique opportunity to do something different. NIAMS was looking for proposals that would really open doors and use the money in ways different from business as usual. We wanted to ask new questions that otherwise wouldn’t be possible.”

Other institutes took other paths. James Rosenbaum, MD, is chair of the division of arthritis and rheumatic diseases and the Edward E. Rosenbaum professor of inflammation research at the Oregon Health and Science University in Portland. Due to his research interests, much of his funding comes from the National Eye Institute.

“There wasn’t one single avenue for getting the money,” he says. “Some institutes took the money and looked at their backlog of unfunded projects. Some used administrative supplements to fund previously committed projects at higher levels. Many used a number of different approaches.”

There were at least two major challenges seen by researchers in the language of the ARRA. One was that all money had to be spent within two years. The second was a short deadline for submitting proposals.

Two-year Funding

“Most rigorously scientific projects will not fit well into a two-year time period,” noted Daniel Lovell, MD, professor of pediatrics at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. “The upside is that it allowed researchers to focus on developing mechanisms and approaches that potentially could change the face of medical research if follow-up funding is available. They are building consortiums and capabilities to do longer term large studies.”

Dr. Carter acknowledges that this was a concern and limited the projects that could be funded. “In our experience, it is very hard to do any kind of real clinical trial within that timeframe,” he says. “Usually just getting all the things like study design, Institutional Review Board approval, and getting regulatory okays means 18 months pass before you can begin patient accrual. In the language of the RFA, we tried to make it clear we were discouraging clinical trials without some very compelling reason to think it could be completed quickly.”

Large Numbers of Applicants

Despite the short timeline, the ARRA grants had no shortage of applicants. For example, one of the smaller funded mechanisms, the Challenge Grants, drew around 20,000 applications for $200 million in grants available throughout the NIH.

Michael Holers, MD, head of the division of rheumatology at the University of Colorado in Denver decided to not participate in the ARRA program. He summed up many of the problems voiced. “No one from this department, including me, decided to participate directly, and I suspect these decisions were based on many factors,” he says. “I think that the reasons would include the published scope of the ARRA grants, the time available to write a grant versus [time] needed for other commitments, the likelihood of a successful application with the anticipated number of funded proposals versus the expected number of submissions, other personal and professional commitments, and the availability of other grant sources to support a faculty member’s research that might have otherwise gone in the ARRA.”

Influx of New Money

From the standpoint of investigators, the biggest plus was the influx of more money into a research system sorely underfunded in recent years. “There is no question that during the last few years, virtually every institute was faced with unreasonably low cutoff points and there was a backlog of superb science going unfunded,” says Dr. Rosenbaum. “As a reviewer, I dreaded every time we got together, knowing that only about one request in eight would see any money. I am unhappy because the funding is for only two years, but thrilled because I would have gotten no money without the ARRA.”

Overall, those interviewed for this article were pleased with the work of NIAMS and other NIH institutes getting the program up and running under an extremely tight deadline.

“The NIH generated a very impressive list of topics with very good relevance to translational research and patient care,” says Mary Crow, MD, director of rheumatology research at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City. “They did an amazing job and it was certainly a pleasure to see grant money become available.”

The NIH generated a very impressive list of topics with very good relevance to translational research and patient care.

—Mary Crow, MD

What’s Next?

The big question asked by all the experts is: “What happens next?” Will there be a big monetary black hole when the two years is up, or will other grant programs fill the void?

“Nobody knows the answer to the ‘What is next?’ question,” says Kathryn Liszewski, a research scientist in rheumatology at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “We are hopeful, but also feel uncertain. As the economy improves, one could consider that standard funding levels would improve, too. It is an open question for now.”

Dr. Lovell wonders whether the advances coming from ARRA funding will be sustained after the two years of funding end. “The critical piece is, Can all of these developments and new consortiums and syndicates being set up be transitioned and continue to operate after the ARRA grants expire?” he says. “Funding needs to rise on a long-term basis above what it has been recently. We are currently funding only 3 to 5% of the submissions. It is a tragedy because probably many of the grant applications could result in important or worthwhile findings.”

In addition, the two-year grants mean that the search for money to continue projects begins almost immediately. “Writing of the grant alone is a commitment of labor and time,” says Dr. Rosenbaum. “From the time a proposal is submitted until you hear about funding is usually eight or nine months. With these two-year grants, you are going to have start looking for additional money after the first year. Establishing tangible evidence of scientific productivity that quickly will be ulcerogenic.” He is also concerned about the human infrastructure put in place by the ARRA. If funding falls back to 2008 levels, he wonders if the jobs created for everyone from investigators to laboratory technicians can be sustained through other funding sources.

Dr. Carter acknowledges that this is an X-factor in the ARRA process. “We say thanks to Congress for allowing us to do something really special, but there is no question that there may be problems two years from now.”

Nevertheless, rheumatology researchers are making good use of the ARRA funds to launch new research projects, support ongoing investigations, and create partnerships and consortia to further understanding of rheumatic disease.

Kurt Ullman is a freelance writer based in Indiana.