PHILADELPHIA—William “Bill” R. Palmer, MD, MACR, was the first board-certified rheumatologist in Omaha, Neb., where he spent his entire 43-year clinical career and established himself as a great clinician, mentor and educator. Although Dr. Palmer passed away from metastatic thyroid cancer in August 2021, his memory lives on through his physician colleagues and at ACR Convergence 2022 in a session titled Rheumatology Research Foundation Memorial Lecture to Honor William R. Palmer, MD, MACR: CARE: Clinical Pearls: Rheumatoid Arthritis.

PHILADELPHIA—William “Bill” R. Palmer, MD, MACR, was the first board-certified rheumatologist in Omaha, Neb., where he spent his entire 43-year clinical career and established himself as a great clinician, mentor and educator. Although Dr. Palmer passed away from metastatic thyroid cancer in August 2021, his memory lives on through his physician colleagues and at ACR Convergence 2022 in a session titled Rheumatology Research Foundation Memorial Lecture to Honor William R. Palmer, MD, MACR: CARE: Clinical Pearls: Rheumatoid Arthritis.

The invited speaker for this event was Michelle Ormseth, MD, MSCI, assistant professor of medicine, Division of Rheumatology and Immunology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and the topic of her lecture was individualized treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. The talk was structured around several clinical cases.

Methotrexate Dose Escalation

The first case was of a 55-year-old woman who presents with two months of morning stiffness, pain, and swelling in her hands and is found to have positive rheumatoid factor and cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies. Dr. Ormseth polled the audience as to what would be the best initial treatment for this patient, and more than 60% responded correctly that this would be to initiate 15 mg of oral methotrexate weekly and increase by 5 mg every four weeks to a target dose of 20 to 25 mg weekly. This strategy is based on recommendations from the 2021 ACR Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis, in which initiation/titration of methotrexate to a weekly dose of at least 15 mg by four to six weeks is conditionally recommended over initiation/titration to a weekly dose of <15mg.1

With respect to the best way to escalate methotrexate dose, Dr. Ormseth cited a study comparing the efficacy, safety and tolerability of a usual dose escalation strategy (i.e., 5 mg every four weeks) vs. a fast escalation strategy (i.e., 5 mg every two weeks). The authors of this study found that, although both regimens had similar efficacy over 16–24 weeks, the fast strategy resulted in more gastrointestinal side effects over the initial eight weeks.2 Thus, a slower approach may be more likely to help patients achieve control of disease without increasing risk of side effects.

Fatigue & Exercise

In the second case, Dr. Ormseth described a 42-year-old woman with seropositive, nonerosive rheumatoid arthritis on triple therapy with methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine and sulfasalazine who has seen considerable improvement in her arthritis symptoms but is experiencing ongoing fatigue. To address this patient’s fatigue, Dr. Ormseth pointed to a clinical trial in which 96 patients with rheumatoid arthritis were randomized to one of three groups: pedometer use and step-monitoring diary, pedometer and diary plus step targets, or a control group in which education about increasing physical activity was the only intervention.3

At 21 weeks of follow-up, both intervention groups had significantly increased their number of steps and also demonstrated statistically significant improvement in fatigue as rated by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System seven-item questionnaire.3 Dr. Ormseth used this study to illustrate the potential role for increased exercise in addressing symptoms of fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Tofacitinib & Cardiovascular Disease

In the third case, a 70-year-old man with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis and a significant history of cardiovascular disease is described as having ongoing disease activity despite subcutaneous methotrexate at full dose. When considering additional treatment options, Dr. Ormseth noted that tofacitinib would be among the riskier choices for this patient.

This is based on the ORAL Surveillance study, in which patients aged 50 and older with moderate to severe RA, one or more cardiac risk factors and inadequate response to methotrexate were divided into one of three clinical arms: 5 mg of tofacitinib given twice daily plus methotrexate, 10 mg of tofacitinib given twice daily plus methotrexate (after the drug safety monitoring review, this dose was lowered to 5 mg given twice daily) or a tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) inhibitor plus methotrexate.4

The study demonstrated that tofacitinib combined with methotrexate was not non-inferior to TNF inhibitors plus methotrexate. The number needed to harm for major adverse cardiac events over one year was 567 for 5 mg of tofacitinib twice daily and 319 for 10 mg of tofacitinib twice daily.4 Independent risk factors for major adverse cardiac events included current smoking, aspirin use, being 65 years or older and being male. In addition, the highest rates of major adverse cardiac events were seen in patients with coronary artery disease and in patients with a high risk of major adverse cardiac events based on traditional risk factors.5 Dr. Ormseth summarized these findings in the form of a clinical pearl that states how tofacitinib should generally be avoided in patients with cardiovascular disease.

RA & Hepatitis B

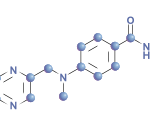

The fourth case was of a 44-year-old woman with seropositive, erosive rheumatoid arthritis who has been treated with methotrexate and sulfasalazine but has not been able to tolerate increased doses of these medications and has high disease activity. On lab studies, she is found to have a history of hepatitis B infection.

Using the 2021 ACR guideline, Dr. Ormseth explained that prophylactic antiviral therapy is strongly recommended over frequent monitoring alone for patients who are positive for hepatitis B core antibody and are planning on initiating rituximab.1 In addition, for patients with evidence of chronic hepatitis B infection (i.e., hepatitis B core antibody positive and hepatitis B surface antigen positive), prophylactic antiviral therapy is strongly recommended over frequent monitoring alone prior to starting biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) or targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs).

Finally, frequent monitoring alone is conditionally recommended over prophylactic antiviral therapy for patients initiating a tsDMARD or a bDMARD other than rituximab if they have evidence of a resolved hepatitis B infection.1 Dr. Ormseth noted that research on this subject has shown that abatacept as well as rituximab both are associated with a high risk of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and resolved hepatitis B infection.6

In Sum

The lecture from Dr. Ormseth provided many clinical pearls regarding the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and grounded these recommendations in the context of patient cases.

Jason Liebowitz, MD, completed his fellowship in rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, where he also earned his medical degree. He is currently in practice with Skylands Medical Group, N.J.

Jason Liebowitz, MD, completed his fellowship in rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, where he also earned his medical degree. He is currently in practice with Skylands Medical Group, N.J.

References

- Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021 Jul;73(7):924–939.

- Jain S, Dhir V, Aggarwal A, et al. Comparison of two dose escalation strategies of methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: a multicentre, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Nov;80(11):1376–1384.

- Katz P, Margaretten M, Gregorich S, et al. Physical activity to reduce fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018 Jan;70(1):1–10.

- Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jan 27;386(4):316–326.

- Charles-Schoeman C, Buch M, Dougados M, et al. Risk factors for major adverse cardiovascular events in patients aged ≥50 years with RA and ≥1 additional cardiovascular risk factor: Results from a phase 3b/4 randomized safety study of tofacitinib vs. TNF inhibitors [abstract 0958]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 Oct;73(suppl 9).

- Chen MH, Lee IC, Chen MH, et al. Abatacept is second to rituximab at risk of HBsAg reverse seroconversion in patients with rheumatic disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Nov;80(11):1393–1399.