SewCream / shutterstock.com

A phase 3 trial described in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) highlights the potential of a C5a receptor inhibitor, avacopan, for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis.1 Avacopan may potentially offer a steroid-sparing option for the treatment of this serious disease.

Current Treatment of ANCA-Associated Vasculitis

Morbidity and mortality from ANCA-associated vasculitis have improved in recent decades, partly due to the introduction of newer treatments, including rituximab and other agents. Currently, most patients with severe ANCA-associated vasculitis are placed on a tapering dose of glucocorticoids, paired either with cyclophosphamide or rituximab. More recently, many patients have been placed on a remission maintenance regimen with rituximab.2

However, clinicians continue to use substantial doses of glucocorticoids for remission induction, maintenance therapy, flare management and relapsing disease. Side effects of glucocorticoid use include weight gain, diabetes, cataracts, hypertension, osteoporosis, neuropsychiatric symptoms and opportunistic infections, among others. These contribute to poor quality of life and worsen overall morbidity and mortality.

David R.W. Jayne, MD, a professor of clinical autoimmunity at the University of Cambridge and director of the Vasculitis and Lupus Service at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, England, is the lead investigator for the recent NEJM study. He points out another problem with current glucocorticoid-laden regimens: Patients often don’t truly achieve lasting remission. “We sort of control the disease, but if you take the kidney for example, 50% of patients still have signs of nephritis at six months on high-dose steroids and rituximab,” he says.

Shubhasree Banerjee, MD, MBBS, an assistant professor of clinical medicine in the Division of Rheumatology at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, a vasculitis expert who was not involved in this study, notes that over the past few years, researchers in the broader field of vasculitis have been trying to develop treatment plans with lower doses and shorter courses of glucocorticoids.

Complement Inhibitors

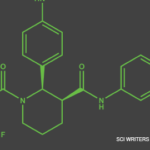

The dominant role of neutrophils is one factor that distinguishes ANCA-associated vasculitis from other kinds. From work in both mouse models and human disease, we know activation of the alternative complement pathway plays a role in the pathogenesis of ANCA-associated vasculitis. C5a, produced when this pathway is triggered, activates and attracts neutrophils, which then activate more complements and neutrophils, creating a complex, positive feedback loop. Avacopan is an oral C5a receptor antagonist that selectively blocks the effects of C5a, thus blocking neutrophil attraction and activation.

Dr. Jayne

Dr. Jayne served as one of the investigators in the CLEAR trial, a phase 2 study of avacopan in 67 patients.3 He points out that, partly because of regulatory obstacles, many rheumatology studies have simply added a study drug to standard-of-care therapies, offering no opportunity to demonstrate steroid-sparing effects. But in this phase 2 study, researchers progressively replaced steroids in three phases—eventually going down to no steroids at all—with each stage approved by an independent data monitoring committee. The results demonstrated avacopan’s promise as a steroid-sparing agent.

ADVOCATE Trial

Like the phase 2 trial, the phase 3 trial was set up to demonstrate avacopan’s potential to replace glucocorticoids for ANCA-associated vasculitis.1

Design

Participants were diagnosed with either granulomatosis with polyangiitis or microscopic polyangiitis, two forms of ANCA-associated vasculitis, in accordance with the International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference definitions.4 Ultimately, 331 patients with new or relapsing disease were enrolled from 143 different international centers.

The randomized controlled trial was designed to be both double blind and double dummy. Thus, 166 participants were assigned to receive 30 mg avacopan twice a day orally, with a prednisone placebo, for 12 months. The other half of the participants received oral prednisone in a tapering regimen down to zero at five months, with an avacopan placebo.

Additionally, patients received immunosuppressive treatment, either cyclophosphamide or rituximab, at the discretion of the prescribing physician, as would commonly be done outside of a study setting. No rituximab was given after week 4. To better compare the results of those receiving avacopan vs. prednisone, the researchers reviewed several factors, including whether the patient received cyclophosphamide or rituximab.

Complicating the study design is the fact that many participants were already receiving glucocorticoids as part of their treatment. In a real-world setting, such patients are usually placed on these drugs immediately to help get their disease under control.

Thus, open-label prednisone treatment continued to be tapered for the early part of the trial in both groups. Open-label prednisone had to be tapered to 20 mg or less of prednisone daily before beginning the trial, in both treatment groups. Further, any open-label glucocorticoids had to be completely tapered off by the end of week 4 of the trial, in both groups.

‘50% of patients still have signs of nephritis at six months on high-dose steroids & rituximab.’ —Dr. Jayne

Results

At week 26, 72% of participants in the avacopan group were in remission, as were 70% of patients in the prednisone group (P=0.24 for superiority at week 26; so did not meet significance). At the study’s conclusion at week 52, 66% of patients in the avacopan group were in sustained remission, as were 55% of those in the prednisone group (P<0.001 for noninferiority at week 52). Thus, in terms of remission, avacopan was neither better nor worse than glucocorticoids at week 26, but superior to glucocorticoids at week 52 (P<0.001 for noninferiority at week 26; P=0.007 for superiority at week 52).

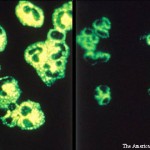

Over 80% of the participants had renal vasculitis. Avacopan also demonstrated potential beneficial effects on renal disease, with improvements in estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria. These improvements were most marked in individuals with the lowest glomerular filtration rate (i.e., patients with stage 4 kidney disease). More severe stage 5 patients were excluded from the study.

Patients in the avacopan group experienced fewer side effects and adverse events related to prednisone exposure, as assessed by the Glucocorticoid Toxicity Index score.5

The rate of serious adverse events related to vasculitis worsening was similar between the two groups, with no prominent safety signal appearing for avacopan. Reassuringly, no participants experienced infections with Neisseria meningitidis. Because C5b is needed to form the terminal complement complex critical for Neisseria protection, such infections are a concern for other types of complement inhibitors, such as eculizumab, that block both C5a and C5b, and not just C5a (e.g., avacopan).

Interpretation & Future Steps

Dr. Banerjee

“This is a landmark study in ANCA-associated vasculitis, which is probably going to change our practice in terms of glucocorticoid use,” Dr. Banerjee underscores. “Avacopan will potentially replace glucocorticoids in induction regimens for ANCA-associated vasculitis.”

However, some caveats and questions remain. Dr. Banerjee points out that avacopan also needs to be studied in certain patient groups excluded from the current study, such as those with alveolar hemorrhage, those on ventilation support and those who have recently received plasmapheresis.

Dr. Jayne notes that some have criticized the study for not employing maintenance rituximab. But at the time the trial was designed, maintenance rituximab was not standard of care. “Most of the differentiation between avacopan and the steroid group happened in the second six months, when the rituximab effect would have been wearing off and when the steroids were stopped,” he adds. “Essentially, those patients were on nothing for the second part of the study. But on the other hand, that did demonstrate the effectiveness of avacopan.”

Dr. Jayne also notes that many questions remain about how the drug may best be used. “Should you just carry on the avacopan long term to help prevent relapse?,” he asks. “We don’t know.” It will require further study to see if the drug might be used in this context in addition to, or in place of, rituximab.

We don’t know definitively that it would be safe to stop avacopan at six months or a year for patients receiving fixed-interval rituximab, Dr. Jayne explains. One theoretical problem with using a complement inhibitor is that complement levels in the blood (including C5a) remain high. It’s not known if removing avacopan when the patient is in remission might trigger a disease flare. From a commercial perspective, the drug may be limited to a one-year license, at least initially, because that was the trial’s duration.

Additionally, researchers will work to understand why some patients didn’t go into remission with avacopan. Although some may have had irreversible disease, some might have responded to more potent blocking of the complement system or perhaps to blocking of other parts of the pathway.

Dr. Banerjee notes the promising trial results will likely encourage further studies investigating other complement-blocking agents in ANCA-associated vasculitis. For example, one ongoing study is testing IFX-1, an intravenously administered monoclonal antibody against C5a, in ANCA-associated vasculitis.6

Dr. Jayne also hopes to explore the drug’s potential in treating lupus nephritis. He and his team have already designed a trial for patients with severe renal disease from ANCA-associated vasculitis, patients with the highest risk of renal failure and death who are currently very difficult to treat. “I think this drug may hold a real hope for [these patients to see] more rapid recovery of their kidneys and avoid dialysis.”

Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD, is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine. She is a freelance medical and science writer living in Bloomington, Ind.

References

- Jayne DRW, Merkel PA, Schall TJ, et al. Avacopan for the treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 18;384(7):599–609.

- Tieu J, Smith R, Basu N, et al. Rituximab for maintenance of remission in ANCA-associated vasculitis: Expert consensus guidelines. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020 Apr 1;59(4):e24–e32.

- Jayne DRW, Bruchfeld AN, Harper L, et al. Randomized trial of C5a receptor inhibitor avacopan in ANCA-associated vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017 Sep;28(9):2756–2767.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised international Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jan;65(1):1–11.

- Miloslavsky EM, Naden RP, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. Development of a Glucocorticoid Toxicity Index (GTI) using multicriteria decision analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Mar;76(3):543–546.

- Safety and efficacy study of IFX-1 in add-on to standard of care in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA). Clinicaltrials.gov.