Approximately 40% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) experienced episodic symptoms of inflammatory arthritis before they received a clinical diagnosis, according to research from Ellingwood et al. This study provides new information about how frequently palindromic rheumatism precedes full-blown RA and yields insights about the specific traits that may result in RA.1

Approximately 40% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) experienced episodic symptoms of inflammatory arthritis before they received a clinical diagnosis, according to research from Ellingwood et al. This study provides new information about how frequently palindromic rheumatism precedes full-blown RA and yields insights about the specific traits that may result in RA.1

Background

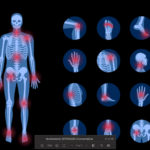

Researchers apply the term palindromic rheumatism to periodic attacks of articular and periarticular inflammation, which most commonly affect one joint at a time, typically the fingers, wrists or knees.2 Attacks last from hours to days and resolve spontaneously. Although radiographic damage from these attacks is not evident, the periods of inflammation can be associated with temporary increases in inflammatory markers.3

Various diagnostic criteria for palindromic rheumatism have been proposed. One set of diagnostic criteria requires recurrent attacks of arthritis in one or more joints lasting a few hours to one week, with physician verification of at least one attack. Additionally, the criteria require subsequent attacks in at least three different joints, as well as physician exclusion of other possible causes of arthritis.2 Other criteria have made other additions, such as lack of radiographic damage.1

The prevalence of palindromic rheumatism is not well established. Although its frequency may be significantly less than RA, it may occur more frequently than previously believed.1 One retrospective Canadian study found an incidence of one case of newly diagnosed palindromic rheumatism for every 1.8 cases of newly diagnosed RA over a two-year period.4

Currently, it’s unclear if palindromic rheumatism should be considered a distinct diagnostic category or part of the RA disease spectrum.5 Estimates from the current literature put the risk of progression from palindromic rheumatism to RA at about one in three. However, some studies report higher rates.1

Previous research has established that patients with palindromic rheumatism have high rates of positivity for serological markers, such as rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs).5 Additionally, the presence of RF and ACPAs have both been associated with the progression of palindromic rheumatism to RA.6,7 Yet many of these patients, even seropositive ones, never develop persistent RA—even after long follow-up periods.5

The optimal treatment of palindromic rheumatism is also a matter of debate. Janet Pope, MD, MPH, FRCPC, professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology, University of Western Ontario Schulich School of Medicine, London, Ontario, says, “There are few studies of palindromic rheumatism and how to treat it. Often, we use non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.”